Brutal Warfare Continues on the Frontier in 1782

Although Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown in October 1781 and peace talks began in Europe soon thereafter, the brutal warfare in the Ohio Country and Kentucky continued unabated. Little did talks taking place in comfortable parlors thousands of miles away affect the Indians and Kentuckians, they were dealing with a daily dose of life and death affairs on the frontier.

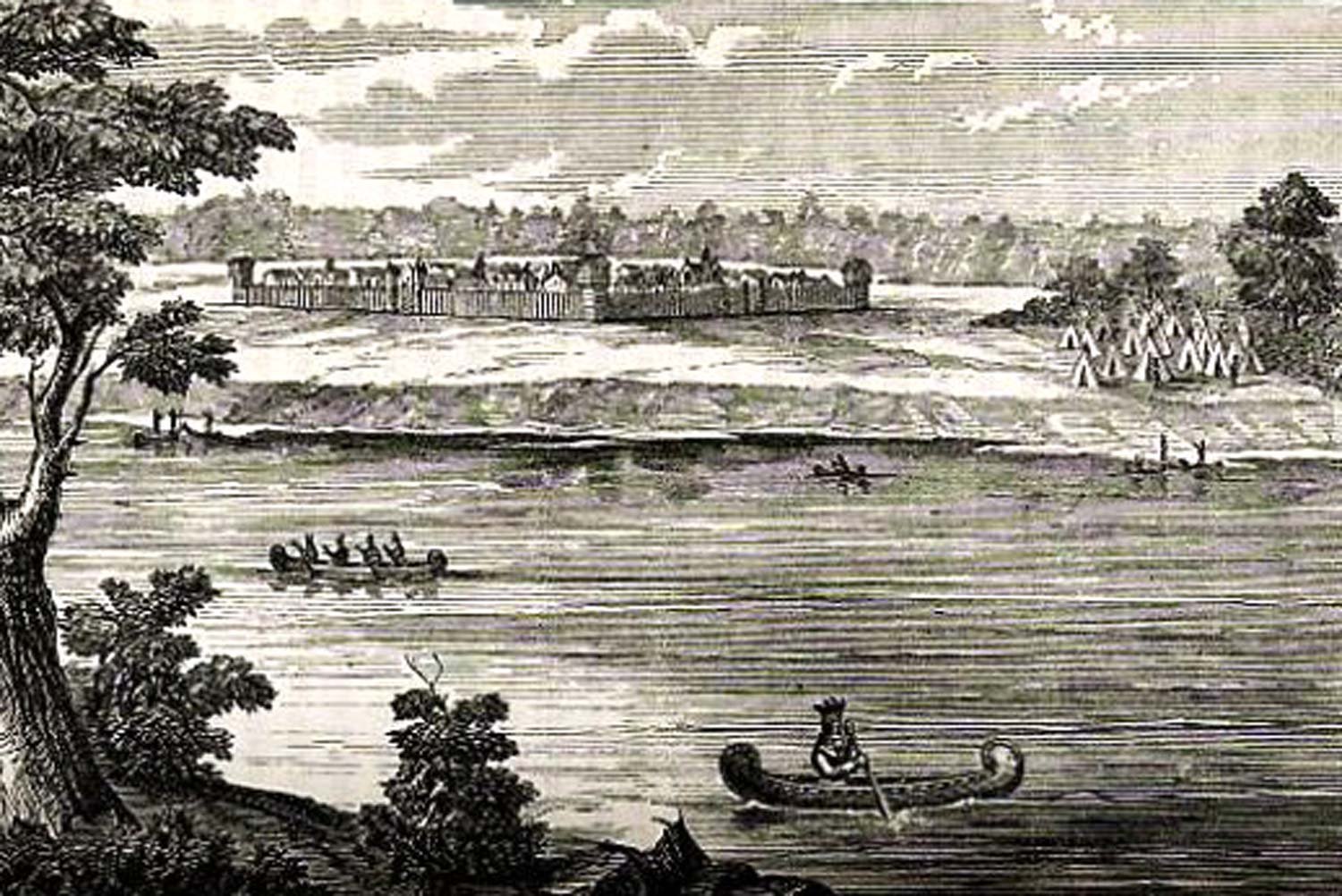

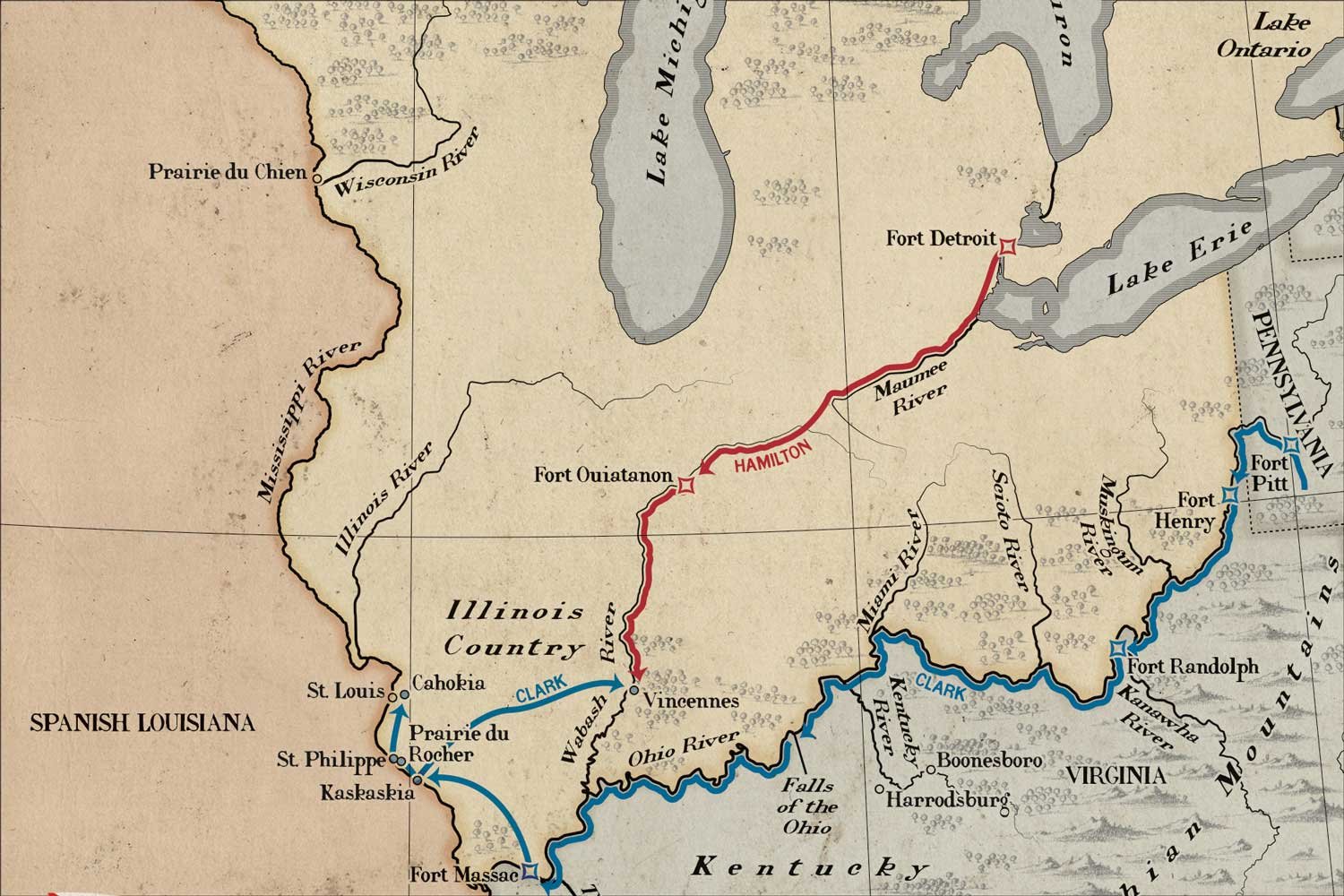

Given negotiations were underway to end the conflict, the most compelling question of the day with the greatest strategic consequences was “Who gets the Ohio and Illinois Countries, the vast territory from the Ohio to the Great lakes and west to the Mississippi?” We must remember that when the American Revolution began in 1776, the land across the Ohio River from Kentucky, stretching from Fort Pitt to the muddy waters of the Mississippi, was the British Province of Quebec, a valuable property recently wrested from France. The Brits had no intention of giving it up.

In the eighteenth century, wars were generally settled under two ancient legal concepts, status quo ante bellum (“the situation as it existed before the war”) and uti possidetis (“as you possess, so shall you possess”). The one method or the other for ending a conflict was selected in large part by the amount of territory captured during the conflict.

For instance, because England had captured most of Canada during the French and Indian War, they followed the principle of uti possidetis when negotiators signed the Treaty of Paris (1763) and England was granted Canada. During our War of 1812, almost no land was captured by either side, and they used the principle of status quo ante bellum for the Treaty of Ghent. Due to these considerations, it was imperative that the vast lands George Rogers Clark had painstakingly captured in 1778-79 be defended until final terms were determined by the peace commissioners.

In a clear example of the disconnect between those in Kentucky who had been living with the daily terror of Indian atrocities for six years and the politicians back east safe in Richmond, Governor Benjamin Harrison advised Colonel Clark to not do anything to antagonize the Indians. Harrison urged “the citizens on our frontier to use every means in their power for preserving a good understanding with the savage tribes.”

Clark was incredulous at Harrison’s instructions and reminded the Governor that the British and their Indian allies did not exactly follow the rules of war or its moral niceties. Moreover, one of Clark’s spies had relayed word Major Arent DePeyster, commander at Detroit, planned to launch an invasion of Kentucky in the spring of 1782 to “lay the whole country waste.”

Harrison and the Virginia legislature then ordered Clark, as commander of the Kentucky militia, to build forts at three strategic locations, the mouths of the Kentucky and Licking Rivers and Limestone Creek, and to man them each with sixty-eight men. It was a good plan, but they failed to provide any funding to accomplish these tasks telling Clark he would “have nothing to depend on for the present but the virtue of the people.” Not surprisingly, no forts were erected and, when the onslaught came, Clark was blamed by the settlers.

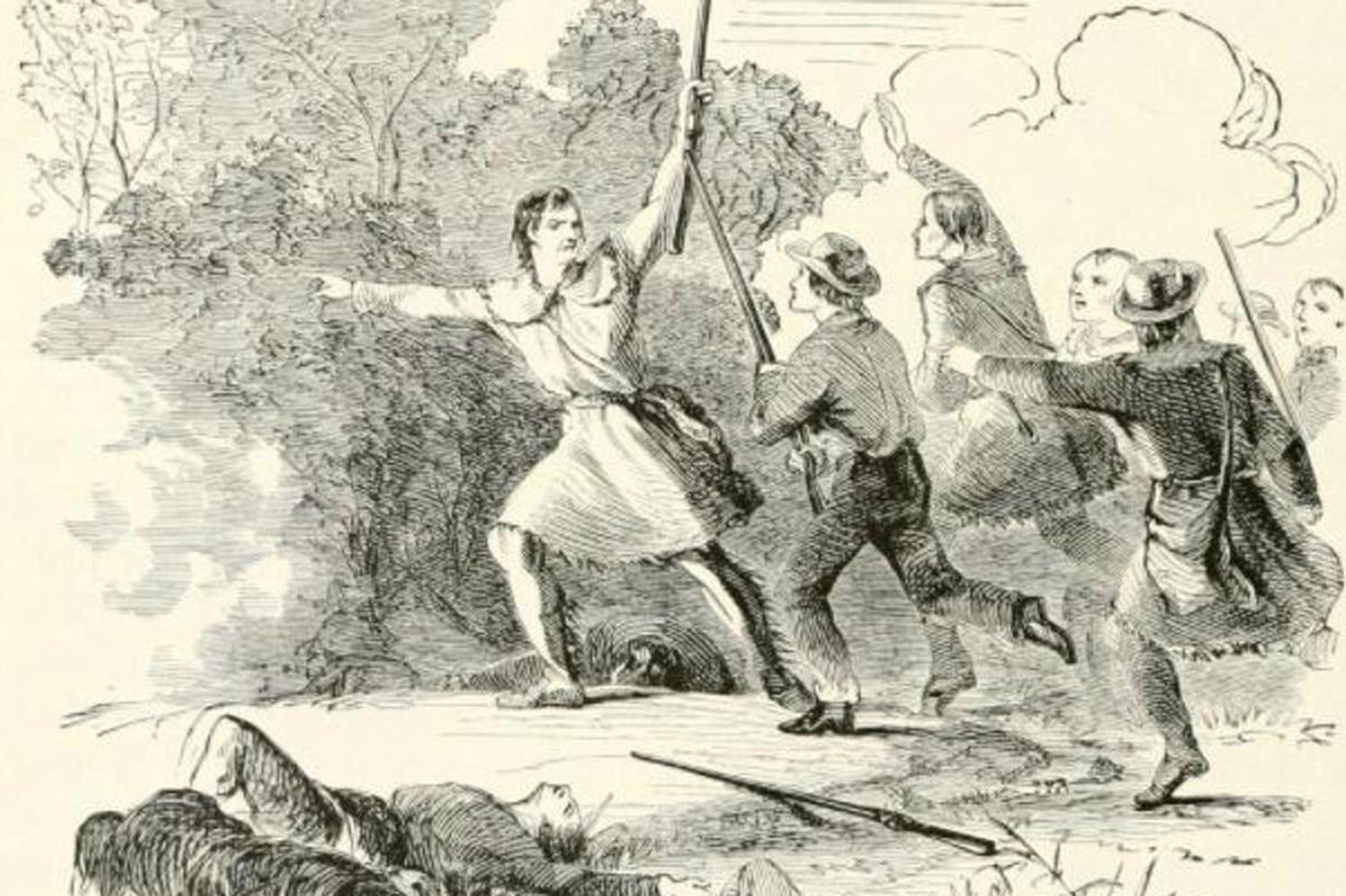

“Massacre of the Christian Indians.” New York Public Library.

Forty-seven Kentuckians were either killed or captured in the first three months of the year, and it got worse as the year rolled on. In one example of the inconceivable brutality practiced by the Indians, warriors were besieging a strong blockhouse at Estill’s Station and wanted to draw the defenders out of the fort. To do so, the Indians took a small girl they had taken captive and scalped her alive in front of the fort. Twelve enraged Kentuckians burst from the blockhouse to rescue the girl - all were killed by the savages.

Not surprisingly, the brutality cut both ways. In March, three hundred Pennsylvania militiamen led by Colonel David Thompson went in search of hostile warriors, but only found a tribe of Christian pacifists known as the Moravian Indians. Frustrated by years of suffering at the hands of the natives, the militiamen rounded up ninety six innocent Moravians in the village of Gnadenhutten and proceeded to tomahawk and scalp all of them, 28 defenseless men, 29 women, and 39 children.

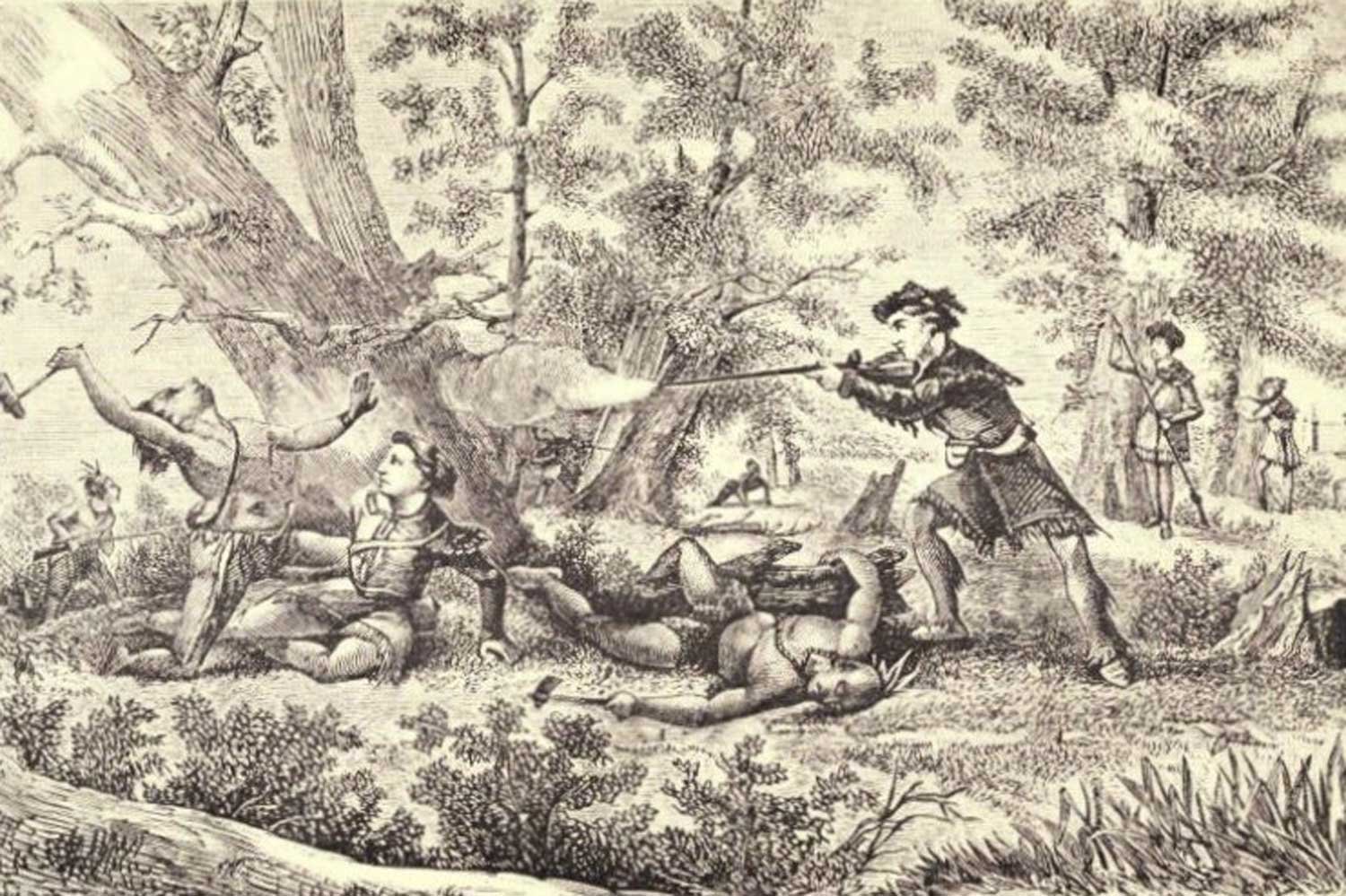

A few months later, on June 4, the tables were turned, and another expedition, this one called the Crawford Expedition, was ambushed and routed in the Battle of Sandusky by vengeance-minded Delaware and Shawnee who killed or tortured to death seventy soldiers. In retaliation for the Gnadenhutten massacre, the Indians tortured the group’s commander, Colonel William Crawford, for two hours before burning him alive at the stake.

Hoping to build on this victory, Captain William Caldwell, a very capable but ruthless Loyalist commander, gathered over 1,000 Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo warriors to accompany his 150-man contingent from Butler’s Rangers on a raid against Wheeling, then part of Virginia. The attack was called off when rumors reached their camp that George Rogers Clark was organizing his own army to invade the Ohio Country. At that point, most of the Indians returned to their villages, such was the fear instilled by Clark.

But Caldwell and about 300 followers crossed the Ohio and headed for the Kentucky settlements, leading to the final British victory of the war.

Next week, we will discuss the final battles in the west. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution and granting independence to the United States of America. Perhaps more importantly for the settlers in Kentucky, the treaty brought an end to the steady stream of English guns and gunpowder to the Indians that had relentlessly attacked Kentucky during the war.