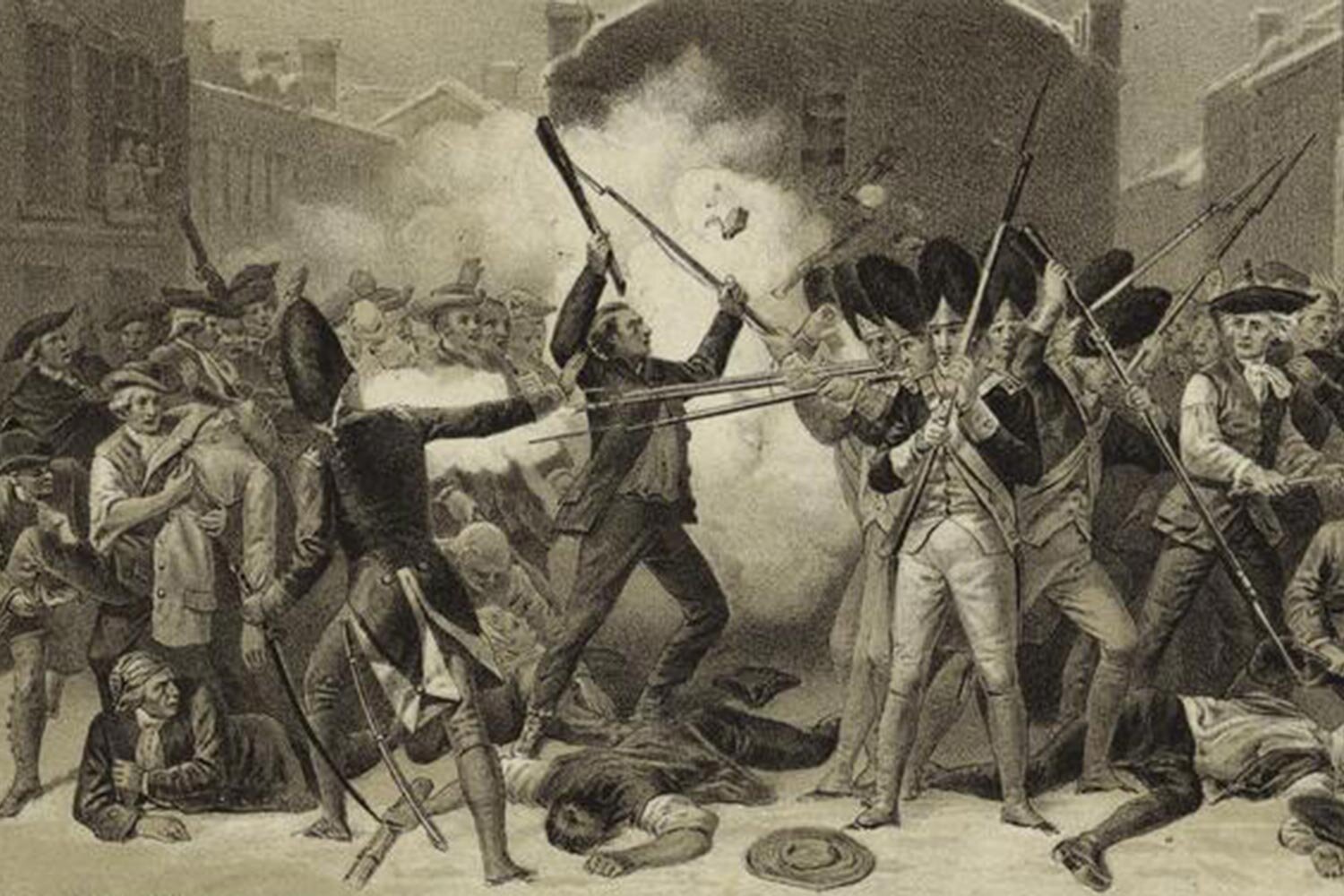

Aftermath of the Boston Massacre

The violence on the evening of March 5, 1770, in Boston is known to us today as the Boston Massacre. It was an unfortunate incident that left five people dead and growing anger between American colonists and leaders in England.

Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, a native of Boston, was quickly on the scene (the Royal Governor was visiting England) that fateful night. He met with town leaders and, by the next morning, had jailed the soldiers who had been involved in the shooting, partly for their own protection. He also reluctantly agreed to move all remaining troops in Boston to Castle Island in Boston Harbor. Unfortunately, Hutchinson and other British officials were now left with no means of enforcing the law.

On March 27, all nine soldiers were charged with murder and trial dates were set. The problem was finding a capable attorney willing to defend the men, knowing that doing so would risk their reputation, business, and, possibly, their safety.

Josiah Quincy agreed to take the case and asked John Adams, one of Boston’s most respected lawyers and a known patriot (at that time called Whigs), to help him. Adams was a principled man and felt all people accused of a crime deserved adequate legal counsel.

The first trial was Captain Thomas Preston’s, and it began in October 1770. He was quickly acquitted by the jury when no one could prove Preston had given the order to fire. The trial for the remaining eight soldiers opened on November 27, 1770.

John Adams was brilliant in his defense and discredited many so-called “eye-witnesses.” He was able to convince the jury that the soldiers were in fear of their life and acted to defend themselves. Adams reminded the jurors, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” After less than three hours of deliberations, the jury found six of the men not guilty and the other two only guilty of manslaughter, but not murder.

The aftermath of the trial was a bit more jumbled. Sam Adams, John’s cousin, was a master of propaganda and quickly presented a story favorable to Bostonians to the public, both throughout the colonies and in England. In his fanciful tale, the mob was seen as innocent gentlemen, peacefully protesting, and the soldiers cast as aggressors who fired without cause. Partly because his spin was first, it made the greatest impression then and has continued to be the version most Americans know today.

After the trial, Captain Thomas Preston quickly left the army and retired back to his native Ireland where he died in 1798. Thomas Hutchinson, the acting Governor who took the side of the soldiers, was forced into exile from his native Boston and all his property was confiscated by former friends. He died a bitter man in 1780.

Sam Adams continued to agitate for independence. Three years later, he instigated the Boston Tea Party, an event in which his followers tossed 92,000 pounds of British tea into Boston Harbor. He lived to see his dream of an independent America become a reality in 1776, and he proudly signed the Declaration of Independence. In his time, he was called “the Father of the American Revolution.” Later, Sam was elected Governor of Massachusetts for four consecutive terms. He lived to the ripe old age of 81 and passed away on October 2, 1803.

John Adams would go on to be one of our greatest Founding Fathers, and our nation’s second President. He led the debate to approve the Declaration of Independence at the Second Continental Congress, secured numerous diplomatic successes including the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and was our nation’s first Vice President, serving under George Washington for two terms.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should the Boston Massacre matter to us today? This tragic event was both a curse and a blessing and provides useful lessons to us today.

It was a curse in that the violence perpetrated the night of March 5th showed us in our worst light, that of an uncontrolled mob bent on harming others who were simply do their duty. That stain will always be with us.

Additionally, it is a lesson regarding how misguided leaders can inspire their followers to doing bad things. We must choose our leaders wisely.

Finally, the events that evening were also a blessing in that it sparked the spirit of American independence in the hearts of many colonists, and perhaps brought matters with England to a head sooner rather than later.

SUGGESTED READING

The Boston Massacre written by Hiller Zobel is a thorough account of this tragic event. Published in 1996, Zobel covers the background, the shooting, and the trial in a very readable manner.

PLACES TO VISIT

The Old State House in Boston was built in 1713 and was the seat of Massachusetts General Court until 1798. From its balcony, our nation’s independence was announced to the people of Boston. The Old State House is one of the oldest public buildings in America.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

Partly due to Benjamin Franklin’s testimony before the House of Commons, the Stamp Act, which taxed items such as newspapers and legal documents, was repealed by Parliament on March 18, 1766. Unfortunately, this conciliatory measure was immediately undone when Parliament enacted the Declaratory Act which reasserted that all laws passed by that legislative body were binding on the colonies, including those related to taxes.