The Cherry Valley Massacre

The Spring and Summer of 1778 was terribly hard on the Mohawk Valley with partisan conflicts raging across much of New York state, and atrocities committed by both sides. Unfortunately, some of the worst mayhem was still to come.

In October, in response to the Wyoming Valley Massacre, Colonel William Butler (no relation to Loyalist Colonel John Butler) led about 260 Continentals, including Captain Daniel Morgan’s now famous Virginia riflemen, on a punitive raid of two prominent Indian towns, Oquaga (today’s Windsor) and Unadilla. After destroying both villages and depriving the Indians of all their provisions for the winter in this lightning attack, Butler quickly retreated to his base at Schoharie, thinking the raiding season was over.

He could not have been more wrong. John Butler’s hotheaded son Walter, a Loyalist Captain, had “borrowed” his father’s Rangers (the senior Butler was ill) and was on his way to devastate the thriving town of Cherry Valley, thirteen miles south of the Mohawk River and roughly halfway between Cobleskill and German Flatts.

Walter Butler was an interesting character, but not in a good way. Twenty-three at the start of the American Revolution, young Walter had been captured early in the war but soon escaped. Feeling he had been mistreated during his captivity, Butler ached with a desire to strike back at the Patriots. Butler also seethed with anger that his mother and three siblings had been imprisoned by Patriot militia when they could not capture or subdue his father and was embittered by the loss of his birthright property, about 26,000 acres seized by the Patriots.

This pent-up hatred would manifest itself in his ruthless attacks on Patriot sympathizers in the Mohawk Valley from 1778 to 1781. By the time he finally met his Maker on October 30, 1781, Butler was perhaps the most feared and hated man in the Mohawk Valley. It was said that the news of his death and that of the British surrender at Yorktown arrived in the Mohawk Valley at about the same time and that the news of Butler’s death brought more joy to the inhabitants.

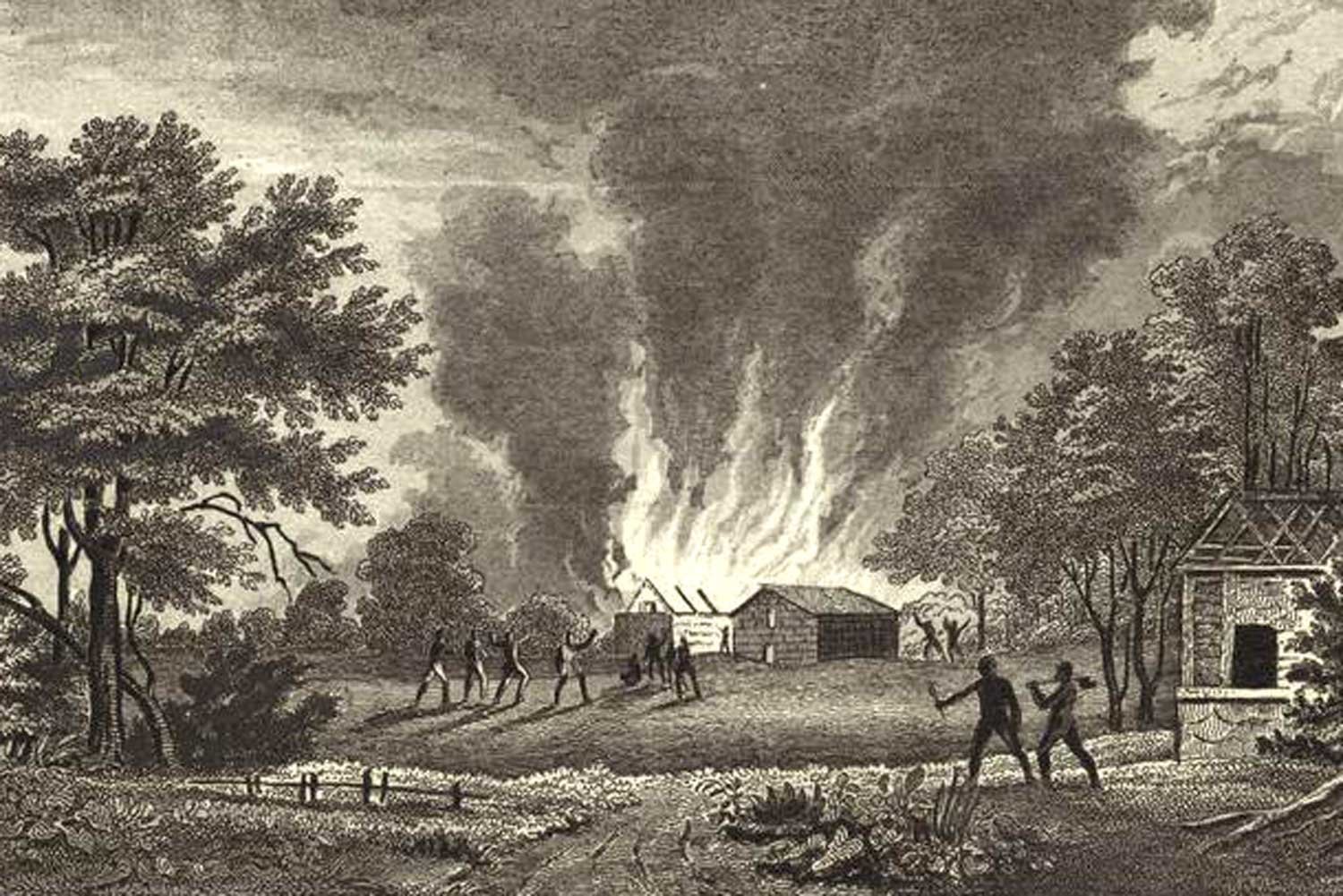

“Cherry Valley Massacre.” Wikimedia.

There had been rumors for some time of a large raiding party coming to Cherry Valley. Unfortunately, the defense of this important town was entrusted to Colonel Ichabod Alden, an inept commander who did little to prepare.

Alden, ignoring the warnings, failed to properly emplace his cannons and did not bother to strengthen the walls of Fort Alden (named by Colonel Alden in honor of himself). To make matters worse, Alden preferred to sleep in the village rather than the fort because the village had more comfortable lodgings. His unit of 260 Continentals did the same.

When Butler’s Loyalist-Indian contingent fell on Cherry Valley in a swirling snowstorm at dawn on November 11, 1778, the garrison and villagers were caught completely off-guard. Everyone raced for the Fort Alden, but most did not make it.

Butler, who was leading his first raid, had vengeance on his mind and instructed his followers that no quarter was to be given. The several hundred Senecas who accompanied Butler and his Rangers were of the same mindset.

Those inside the fort were relatively safe from Butler’s men and his Indian allies so the Senecas took out their frustration on everyone and everything outside the walls. The butchery that followed was unprecedented, even in this most bitter of civil wars, and Butler made little effort to control the Indian’s bloodlust. The Senecas seemed to kill simply for the pleasure of doing so and without any real military purpose.

Captain Daniel Whiting, the senior surviving militia officer, reported finding thirty-three women, children, and infants murdered and scalped amid the rubble and another one hundred soldiers killed. One observer wrote, “I was never before spectator of such a scene of distress and horror. The first object that presented was a woman lying with her four children, two on each side of her, all scalped…There were only three men of the place killed, all the rest being women and children.”

One result of these many raids was that they depopulated this region of upstate New York, driving many farmers from their farms. Prior to 1778, the area had been one of the breadbaskets of the east coast, providing valuable food stuffs for General George Washington’s Continental Army. Washington was determined to reestablish control of the Mohawk Valley and formed a plan to take it back.

Next week, we will discuss the Sullivan Expedition, the American response to the massacres of 1778. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.