St. Clair’s Debacle on the Wabash

The American army commanded by General Josiah Harmar had been badly mauled by the Northwestern Confederacy in the autumn of 1790. Anxious to demonstrate the will and ability to gain control of the Ohio Country, the following March, Congress expanded the army to two regiments and President George Washington appointed Arthur St. Clair, the Governor of the Northwest Territory, to command the new force.

St. Clair, like Harmar, had been a Continental Army general with a mostly successful career, finishing the war as an aide to General Washington. Named a Major General for this new assignment, St. Clair was ordered by Secretary of War Henry Knox to recruit and train two regiments of men and then head north to punish the tribes who had so badly defeated General Harmar. But there was little enthusiasm among the frontiersmen to join the expedition and recruiting was difficult.

Although St. Clair thought it was too late in the season to begin his advance, Knox sent several messages pressuring St. Clair to begin the campaign. The Secretary wrote, “The President enjoins you, by every principle that is sacred, to stimulate your exertions in the highest degree” as Knox and President Washington politically needed a victory to atone for Harmar’s embarrassment the previous year. Finally, in mid-September 1791, St. Clair began his march north from Fort Washington (modern day Cincinnati) with roughly 1,500 men.

Advancing painfully slow with a pack train that stretched back for miles and having to carve their own road through the wilderness, St. Clair’s army often made just a few miles a day. After a week, the army reached the banks of the Great Miami River and Fort Hamilton, and, on October 4, St. Clair’s army crossed to the west bank and continued towards the main Miami villages. Ten days and forty-five miles later, St. Clair halted long enough to erect Fort Jefferson as a forward supply depot and a place of shelter for the wounded and infirm. In a sign of the low quality of the troops and perhaps St. Clair’s leadership skills, the force had been reduced, mostly by desertion and disease, to about 1,100 men.

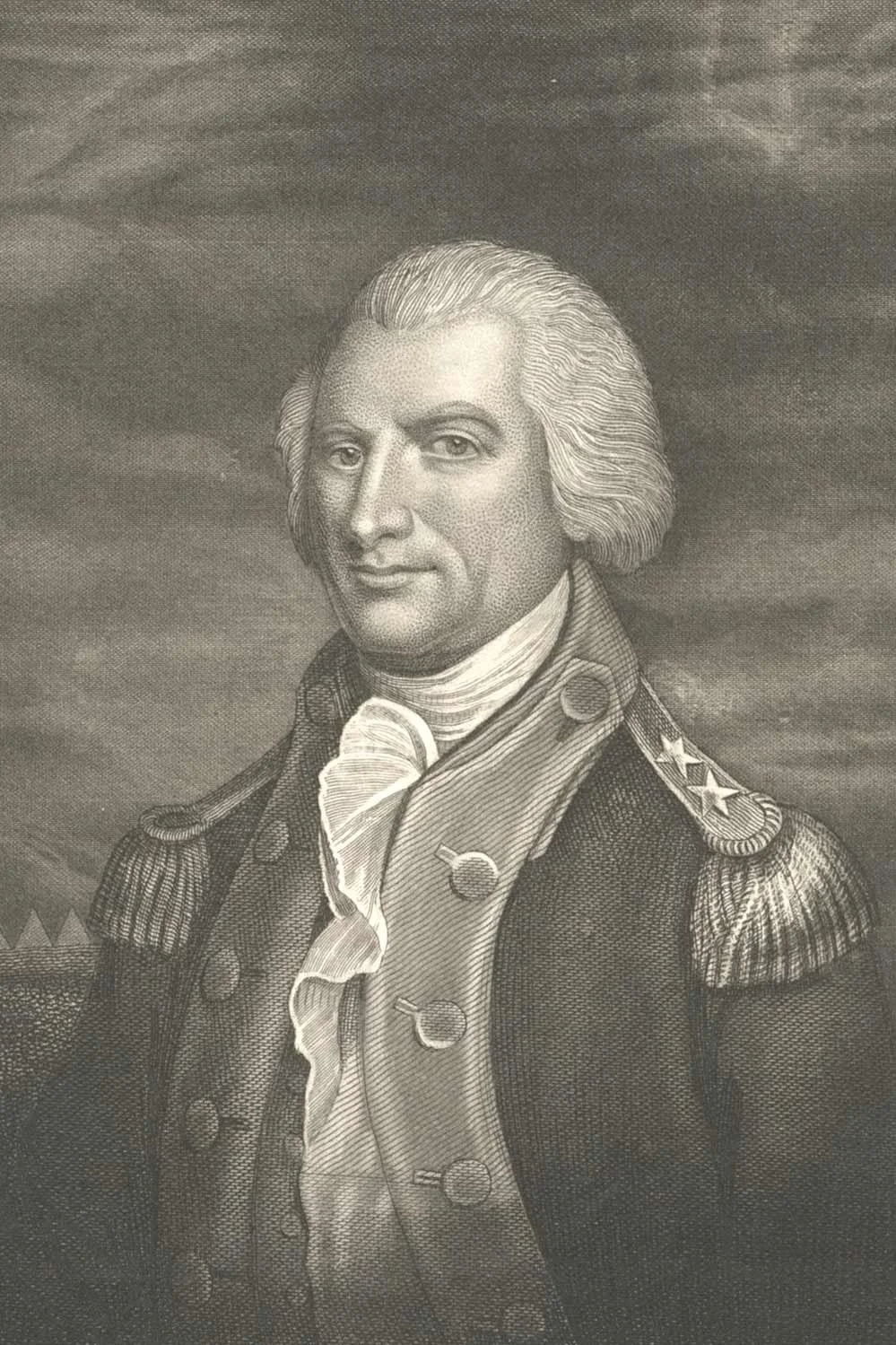

"Arthur St. Clair." New York Public Library.

Arriving at some open ground overlooking a river on November 3, St. Clair halted the column and set up camp. Amazingly, neither St. Clair nor his officers knew exactly where they were. They thought the river to their front was the St. Mary’s when in fact it was the Wabash. They also did not believe any Indians were nearby, despite three soldiers being killed, several horses being stolen, and a scouting party under Captain Jacob Slough reporting “Indians in such numbers that he thought it necessary to draw in his party.” Disregarding these warning signs, St. Clair did not post any picket lines that night nor did he have the men fortify their positions.

At dawn on November 4, in present-day Fort Recovery, Ohio, roughly 1,000 warriors, led by Miami chief Little Turtle and Blue Jacket of the Shawnee, launched a surprise attack on the American camp. The Kentucky militia, bivouacked across the Wabash from the main force, were quickly routed and retreated to the encampment. Despite outnumbering the Natives, St. Clair’s troops were soon surrounded, and the defensive perimeter began to compress into the hollow center, with the panicked militiamen seeking safety from the warriors who seemed to be lurking behind every tree.

To break the Indian line, St. Clair ordered several bayonet charges, even leading one himself despite suffering from debilitating gout in his legs. But the Indians simply yielded ground until the bayonet charge exhausted its energy and then the Indians recommenced their attack.

The Indians had been taught to concentrate their fire on the officers, and within an hour most officers were dead or wounded, adding to the panic among the untrained militia. Recognizing to remain meant certain annihilation, around 9:30am St. Clair ordered a retreat. The few remaining officers led another bayonet charge which parted the Indian line but this time the Americans kept on moving down the road towards Fort Jefferson, some thirty miles away.

The retreat soon became a rout, and the men began to discard muskets, packs, and anything else they could to speed their flight. The wounded who were left behind were soon tomahawked and scalped by the raging Indians. All told, St. Clair’s army lost about 900 men, 630 killed, including thirty-seven officers, and 284 wounded. Although an exact number of casualties for the Indians was difficult to state with certainty, most accounts had them at less than fifty. The Battle of the Wabash was the worst defeat an American army would ever suffer at the hands of a Native American force.

Angry and frustrated at the army’s futility in subduing the Indians, President Washington urged Congress to authorize a force suitable to finally conquer the Northwest Territory. In March 1792, Congress agreed to create a 5,000-man force called the Legion of the United States, the forerunner of our United States Army, and the President selected Anthony Wayne to lead this new contingent. It would prove to be a good choice.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace.