Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 4: Lewis and Clark Leave Civilization Behind

On October 14, 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark met in Clarksville, Indiana Territory, and commenced the most famous partnership in American history. They planned to leave with the spring thaw and reach the Mandan villages, 1,300 river miles above St. Louis, and spend the winter there before proceeding west. On May 21, 1804, the Corps pushed out into the current of the Missouri and, as the men moved north, they entered an enchanting land that very few would ever see again. But despite the idyllic surroundings, the Corps of Discovery was still an independent military expedition traveling in hostile territory.

Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 3: Leaders of the Corps of Discovery

In March 1801, Captain Meriwether Lewis received a letter from Thomas Jefferson, the newly inaugurated president and a family friend, asking Lewis to become his private secretary. At the time, Lewis was a twenty-seven-year-old captain serving as the paymaster for the First Infantry Regiment. Over the next two years, Jefferson tutored Lewis on the lands west of the Mississippi and in the sciences of astronomy, botany, and anatomy in anticipation of an exploratory expedition to the Pacific Ocean. But both Jefferson and Lewis recognized the need to find a capable second officer for the expedition, and the man Lewis wanted to fill this coveted position was William Clark.

Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 2: Thomas Jefferson’s Western Vision

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson drafted his official instructions for a great expedition to explore the Louisiana Territory and asked his private secretary, Captain Meriwether Lewis, to lead it. Once assembled, the Corps of Discovery would operate like a small frontier garrison with rigidly maintained discipline. In the end, the group went forward remarkably prepared for what they would encounter over the next few years, a testament to the thorough planning of President Jefferson.

Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 1: The Search for the Northwest Passage

The dream of finding an all water route across North America, the mythical Northwest Passage, had been imagined since the time of Christopher Columbus, but three hundred years after the Admiral of the Ocean Seas completed his epic voyages, the vast interior of the continent was still essentially unknown to Europeans. As early as 1783, Thomas Jefferson had wanted to send an expedition to explore and chart the great unknown west of the Mississippi, and over the next twenty years, Jefferson tried on several occasions to enlist the support of some brave adventurer to undertake the exploration but with no success.

Louisiana Purchase, Part 4: The Noblest Work of Our Lives

The midnight deal Robert Livingston, United States Minister to France, struck with French Finance Minister Francois Barbe-Marbois to purchase the Louisiana Territory was arguably the most impactful treaty in the history of the United States. While the purchase seemed like a gift from heaven, there were several significant issues with it. For one, the American commissioners were not authorized to purchase Louisiana; they had been instructed to purchase New Orleans and West Florida. Second, they had only been authorized to spend $10 million; they had exceeded that amount by half. Finally, there remained the legality of the purchase as the Constitution did not specifically grant the executive branch the power to purchase new lands.

Louisiana Purchase, Part 3: Napoleon’s Unexpected Gift

When word leaked out that Spain had secretly agreed to transfer Louisiana and, possibly Florida, to France, the news hit like a thunderbolt. President Thomas Jefferson fully understood the significance of trading a weakened Spain for a powerful Napoleonic France as the country’s neighbor. In April 1802, Jefferson wrote to Robert Livingston, U.S. minister to France, to inform Napoleon, “There is on the globe one single spot the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market.” Jefferson directed Livingston, who had been busy for months laying the foundation for the purchase of New Orleans, to warn Napoleon that France acquiring Louisiana “rendered it impossible that France and the United States can continue long friends.”

Louisiana Purchase, Part 2: Western Settlement and the Mississippi River

Because of several treaties in the 18th century, Spain controlled the entire west bank of the Mississippi and the east bank for a stretch of 150 miles, from Natchez to the Gulf of Mexico. Especially unfortunate for western Americans, Spain also controlled the river port of New Orleans, the key to the continent. The rapid influx of Americans into the region following the American Revolution became a great concern for Spanish officials, as the population of Kentucky and Tennessee grew tenfold, from 30,000 to 300,000, between 1784 and 1800.

Louisiana Purchase, Part 1: The Early History of the Louisiana Territory

In 1682, Robert de la Salle, a French explorer and fur trader, reached the mouth of the Mississippi River and claimed the interior of North America for King Louis XIV. Four decades later, Jean-Baptiste de Bienville founded New Orleans, creating a massive strategic arc across North America stretching from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico. And from within this domain, the French controlled the core of the continent and the hugely profitable fur trade. But their hold did not go unchallenged and in a series of wars throughout the eighteenth century, the British dispossessed the French of its colonies in North America. As the final war drew to a close, France secretly transferred Louisiana and the river port of New Orleans to Spain rather than have Louisiana fall into British hands. When Napoleon came to power in 1799, he had visions of reestablishing a North American empire and in October 1800, he forced Spain’s King Carlos IV to give Louisiana back to France.

An Expression of the American Mind

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced into the Second Continental Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution, calling for a complete separation from Great Britain. This leap of faith into the unknown space of independence finally had been publicly demanded and a contentious debate ensued. Congress created a committee to draft a declaration of independence in the event they chose that course of action. The committee included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Robert Livingston, Roger Sherman, and Thomas Jefferson, and chose Jefferson to be the main penman.

Thomas Jefferson’s “Summary View”

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies; concepts that Jefferson had refined over the course of several years.

Thomas Jefferson, the Virginia Barrister

n 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the first internal tax on the American colonies, and thus began a decade of missteps by the British. That same year, Thomas Jefferson concluded his time studying law under George Wythe and began his brief but successful law career. In colonial Virginia, there were two levels of courts – county courts, which were scattered throughout the colony, and the General Court of Virginia in Williamsburg. Jefferson opted to bypass the county courts and try for immediate admittance to the General Court. His brilliance recognized, Jefferson was accepted, and at age twenty-four, he joined a small group of much older attorneys considered the best in the colony, including George Wythe, Edmund Pendleton, and Richard Bland.

The Early Life of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, in a small farmhouse on the frontier of western Virginia, in today’s Albemarle County. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a mountain of a man and well-respected throughout the region as a surveyor who ranged far and wide over the western portions of the colony. Peter’s work brought him significant wealth and put him in contact with the leading authorities in the colony. Sadly, in the summer of 1757, when Tom was fourteen, his father got sick and passed away, leaving behind a widow and eight children and a sizeable, debt-free estate. One of his father’s dying wishes was for Tom to complete his education, and in March 1760, Jefferson entered the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg.

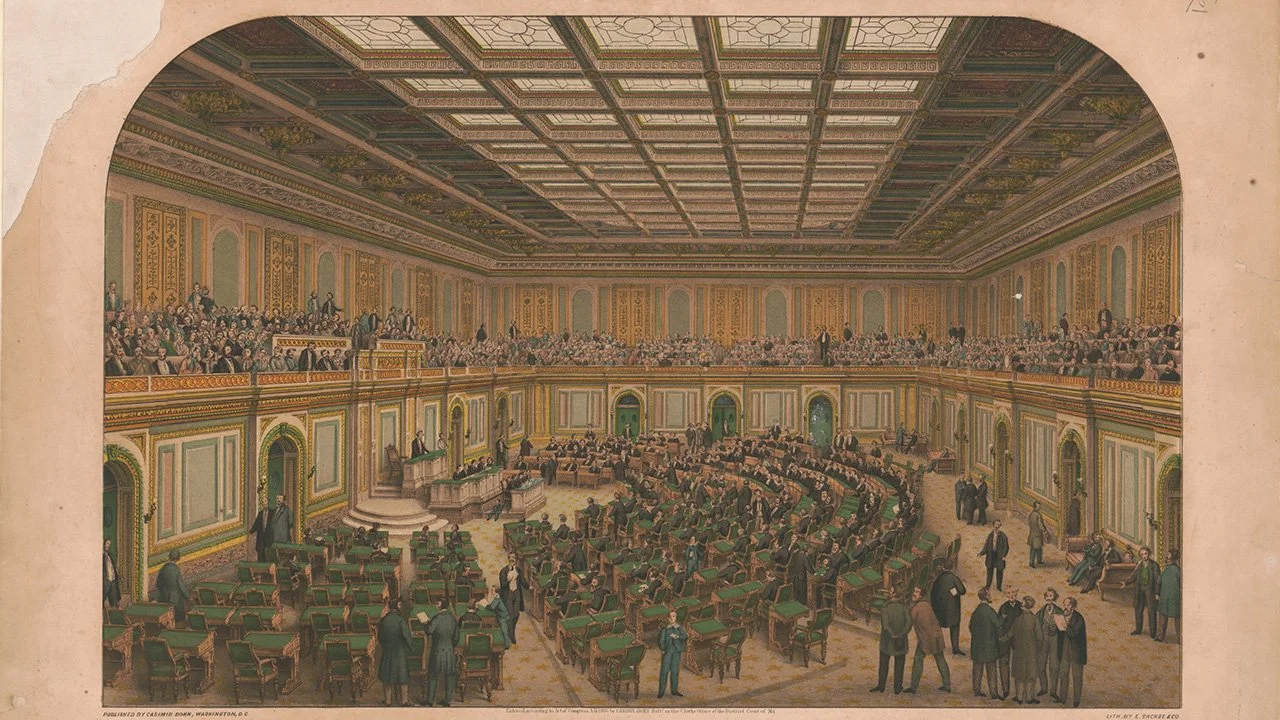

The House of Representatives Chooses Thomas Jefferson

The presidential election of 1800 ended in a tie, as the two Democratic-Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, each received 73 electoral votes. Burr had been added to the ticket to carry his home state of New York, but it was assumed that nationally Jefferson would get the most votes and Burr the second most. When that did not happen, the election moved to the United States House of Representatives in accordance with Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution.

The Election of 1800

The presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.

The Legacy of John Adams

John Adams’s loss to Thomas Jefferson in the presidential election of 1800 was a great disappointment for Adams and marked the end of the public life of this devoted patriot. For a quarter of a century, Adams had been serving at the center of the fight to create and establish the country he loved. By all accounts, he arguably did more to shape the United States than any other Founding Father, except for the incomparable George Washington.

The End of the Quasi-War

n November 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte took over control of the French government with the support of wealthy French merchants who owned lucrative plantations in the Caribbean. Bonaparte was anxious to conclude the Quasi-War, which sapped France’s naval resources and harmed his supporters’ economic interests. The determination of President Adams to stand by his principles, certainly one of his greatest traits, and not expand the conflict with France benefitted the country. But it cost Adams politically as the President lost the support of his own party. By the time the news of the treaty reached America, it was too late to help him in the election of 1800, which he lost to Thomas Jefferson.

The Quasi-War with France

The Quasi-War was an undeclared naval war between France and the United States, fought primarily in the Caribbean and the southern coast of America, between 1798 and 1800. The war resulted from several disagreements with France but was mostly due to French privateers seizing American merchant ships. On April 30, 1798, Congress created the Department of the Navy and appropriated funds to finish six frigates that had been authorized by the Naval Act of 1794. Three were near completion and soon put to sea, and three more followed in the next two years. On July 7, Congress authorized this new United States Navy to begin seizing French ships, marking the “official” start of the Quasi-War.

Relations with France Fall Apart

America’s first armed conflict following the American Revolution was a mostly forgotten fight with France called the Quasi-War and was the culmination of a series of disagreements with our former ally. In 1793, to avoid getting drawn into the latest war between Great Britain and France, President George Washington issued his Proclamation of Neutrality. This declaration angered the French because they considered Washington’s refusal to help them as a violation of the 1778 Treaty of Alliance.