The Iroquois Confederacy

When the American Revolution began, most of western New York state was unsettled by Europeans and remained the dominion of the Iroquois Confederacy. Over the course of the next eight years, the clash of cultures would result in some of the bloodiest and most brutal fighting of the war.

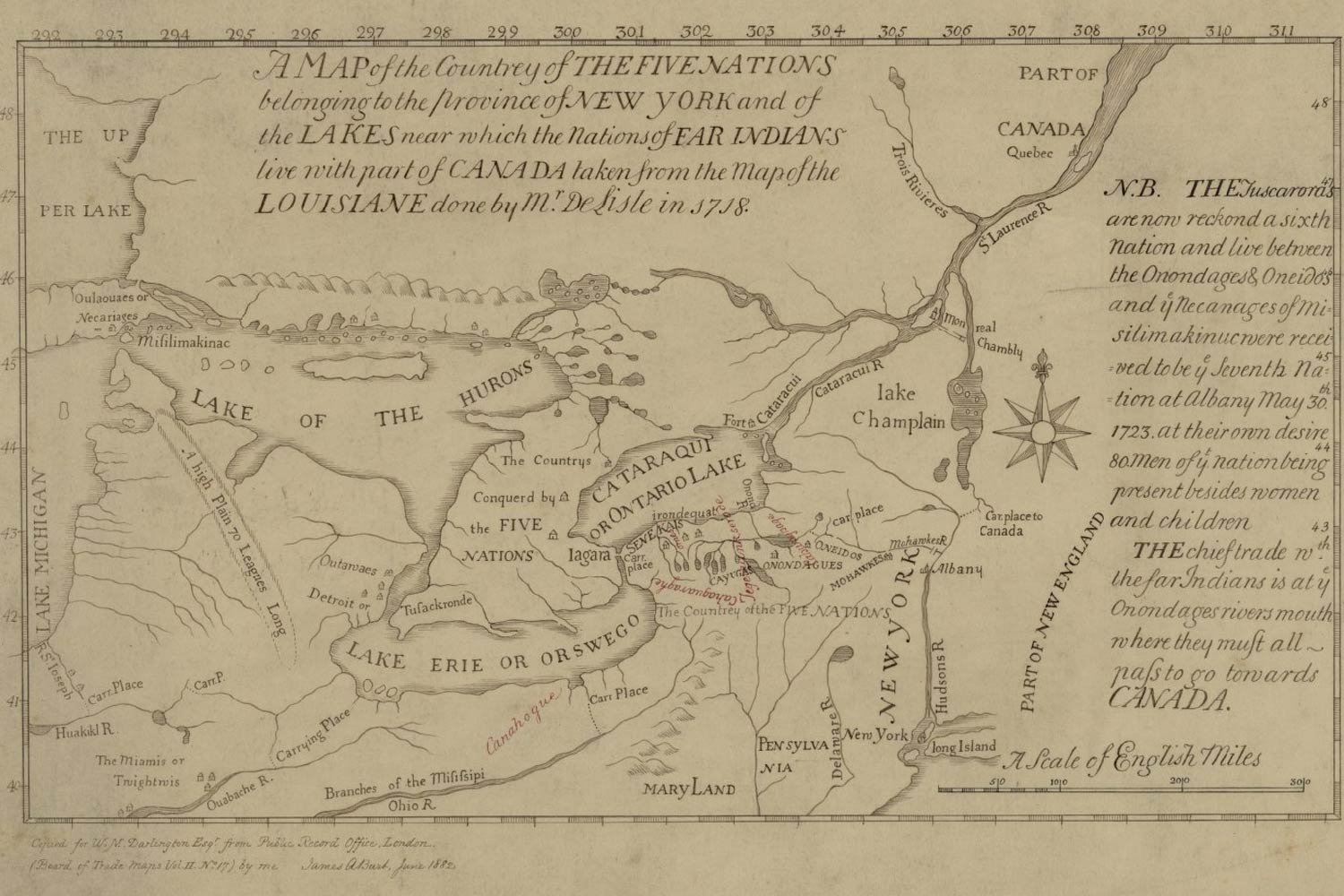

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Five Nations, was given this name because it was originally comprised of five allied Indian tribes (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca; the Tuscarora joined in 1722). The Iroquois were based in what is today the central part of New York state, along the Mohawk River and the Finger Lakes region.

The five nations joined forces sometime in the early 1600s, though the exact year is uncertain. Prior to the Confederation, they had been dominated by other tribes in the area like the Huron and Mohicans. Now that situation changed dramatically. By mid-century, as the Iroquois became better organized than their adversaries, they destroyed the Mohicans and even came to dominate many tribes in New England, demanding tribute from the conquered Indian nations.

The dynamics of the region began to shift in the late 1600s as more and more Europeans got established in the area. The arrivals from the Old World, first the Dutch and then the French and British, had an insatiable thirst for beaver pelts which the Indians happily supplied.

The Europeans also had a seemingly limitless supply of muskets, powder, and ball, the most desired commodities of the Natives. A mutually beneficial barter system of furs for guns was established, but it also intensified the warfare between the tribes for control of the beaver trade.

Whichever tribe had the most furs would obtain the most guns, and whichever tribe had the most guns would dominate the region. Throughout the second half of the 17th century, as beaver became depleted in their home region, the Iroquois expanded their empire into the Great Lakes region and the Ohio River Valley in a quest for more furs. Importantly, the Iroquois also signed a pact with the English in 1677 which solidified their hegemony.

In a series of conflicts known as the Beaver Wars, the Confederacy destroyed and conquered many neighboring peoples such as the Susquehannocks in present day Pennsylvania and greatly weakened the Huron peoples around the Great Lakes. At the height of their power in the early 1700s, the Iroquois controlled a region from Illinois in the west to Michigan in the north and as far south as the hills of Tennessee.

The Confederacy’s greatest strength had always been their ability to stay united. Even during the French and Indian War, all Iroquoian nations had allied with the British, while, not surprisingly, their many enemies such as the Huron took up with the French. With the British victory, the Iroquois became even more dominant in the region.

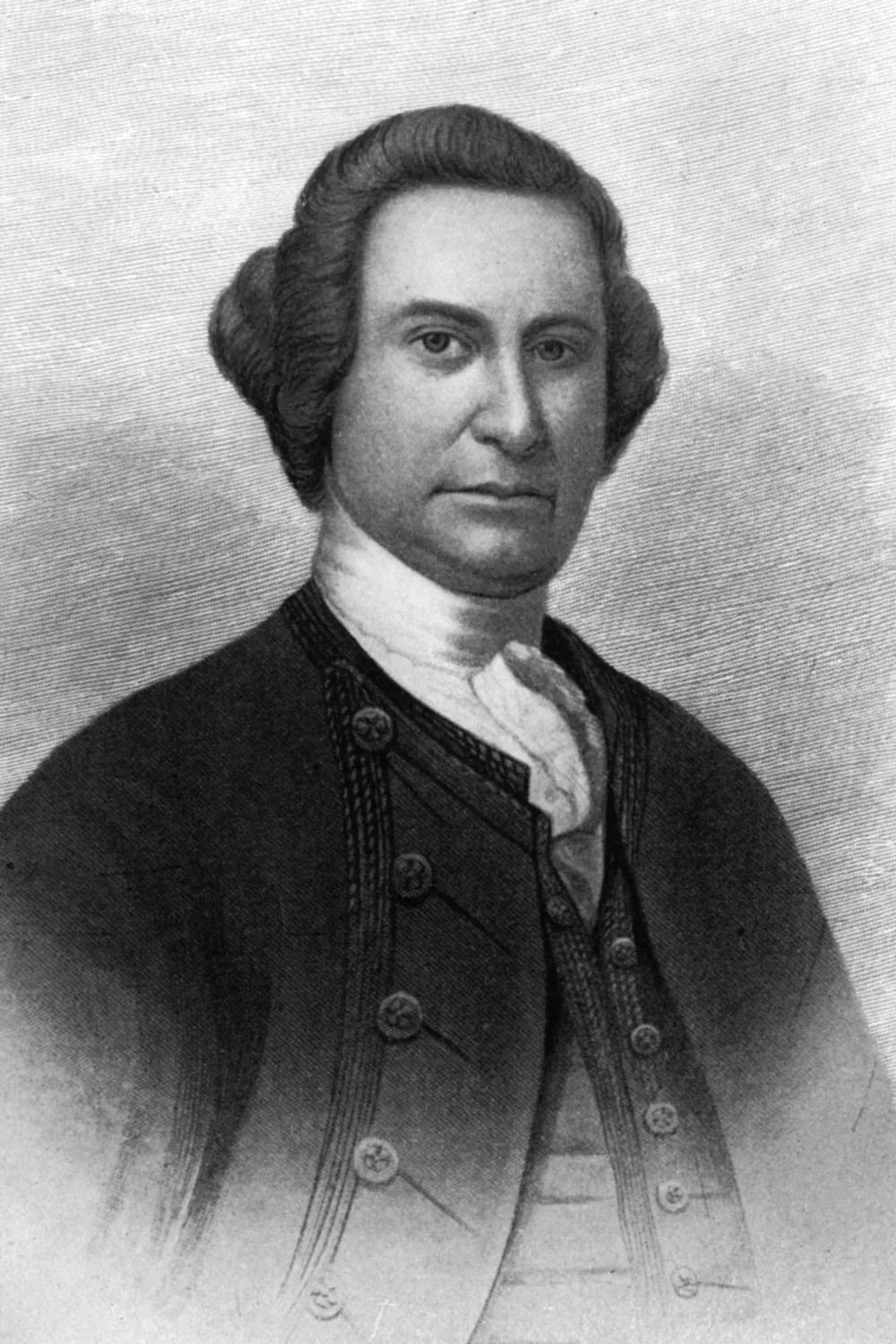

“Sir William Johnson.” Wikimedia.

Throughout the mid-1700s, part of the glue that held the tribes together and allied them to the British was Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet of New York. Sir William had been the long time “king” of Tryon County, a huge county in western New York, and he politically dominated this section of the state to include controlling all tribes of the Iroquois nation.

Sir William, one of the more colorful and powerful men in the history of colonial America, was born in 1715 in Ireland and came to America in 1738 to manage the monumental estate of his uncle, Peter Warren. By the mid-1700s, Sir William ruled his region like royalty and, in 1755, was awarded a baronetcy for his heroic work during the French and Indian War.

Sir William died on July 11, 1774, while presiding over an Indian conference at his seat of power, Johnson Hall, and his untimely death would prove terribly unfortunate to the Iroquois. As European encroachment on native lands had increased, Sir William became the magnet to which all Iroquois tribes attached themselves for protection.

With Johnson’s passing and the pull of the Americans and the English during the American Revolution, the Confederacy splintered apart. While four tribes (Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga) took up with the English, the Oneida and the Tuscarora assisted the American effort.

With the failed British invasions of New York in 1776 and 1777 to subdue the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor, the power of the Loyalists and those tribes allied with the British was significantly weakened. However, they were not broken, and some of their leaders were determined to fight back.

In early 1778, as most American eyes, including General George Washington’s, were turned towards the British army occupying Philadelphia, Loyalist leaders in New York were planning to strike unsuspecting Patriot settlers in the area. The result was a series of bloody massacres, followed by equally bloody reprisals.

Next week, we will discuss the terrible civil conflict in New York and Pennsylvania in 1778. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.