Louisiana Purchase, Part 4: “The Noblest Work of Our Lives”

The midnight deal Robert Livingston, United States Minister to France, struck with Francois Barbe-Marbois, Napoleon’s Finance Minister, on April 13, 1803, to purchase the Louisiana territory was one of the most impactful agreements in the history of the United States. It resulted from months of conversations Livingston had had with numerous French officials, creating a foundation for the details that would follow. But as important as this step was, there remained several hurdles to overcome.

Like most business deals, the first and arguably most critical aspect to be determined was the price to be paid. Napoleon was willing to part with Louisiana primarily to raise funds for his pending war with Great Britain, and so the amount paid by the Americans was hugely critical to closing the deal. The emperor also wanted the transfer to happen fast because he was already gearing up for the next round of battles with the English; peace seemed to bore Napoleon and he was anxious to be back in the field at the head of his Grande Armee.

As instructed by Napoleon, Barbe-Marbois began the talks by stipulating that the price would be 125,000,000 Francs, or roughly $24,000,000, $18,750,000 for the Louisiana territory and another $5,250,000 in debt forgiveness for money France owed the United States for losses suffered during the Quasi War. Two weeks of steady haggling by Livingston and James Monroe finally brought down the price to $15,000,000, $11,250,000 for Louisiana and $3,750,000 for damages to American merchants.

Most of the terms were quickly wrapped up and the monumental agreement was signed by Livingston, Monroe, and Marbois on May 2 but antedated to April 30, 1803. When the signing was done, Livingston, who was on the committee that had drafted the Declaration of Independence, declared to the others, “We have lived long but this is the noblest work of our lives.” But the devil is always in the details, many of which were not ironed out in the haste to close the deal before Napoleon changed his mind, always a concern to the Americans. One key point that was settled was that American acquisition of the Floridas was not included in the terms; they would remain the possession of Spain, at least for the time being. Napoleon promised the American commissioners that he would endeavor to support their efforts to secure this territory, but when pressed to add this language to the contract, Napoleon refused; in the end, he was no help at all.

Among the details left uncertain, were the exact boundaries of what the United States had just purchased. Livingston asked French Prime Minister Talleyrand for clarity on the eastern boundary, especially the land east of the Mississippi adjoining West Florida. Talleyrand, knowing that this unsettled detail would cause mischief in the future, simply remarked, “I do not know. I can give you no direction. You have made a noble bargain for yourselves, and I suppose you will make the most of it.” For the next twenty years, this boundary would be a constant point of contention between Spain and the United States.

“Robert R. Livingston, L.L.D.” New York Public Library.

While the purchase seemed like a gift from heaven, there were several significant issues with it. For one, the American commissioners were not authorized by their instructions to purchase Louisiana; they had been instructed to purchase New Orleans and Florida. Second, the money they were authorized to spend on whatever they acquired was only $10,000,000; they had exceeded that amount by half. Finally, there remained the legality of the purchase as the Constitution did not specifically grant the executive the power to purchase new lands. Moreover, when Thomas Jefferson was not president, he argued that the Constitution must be strictly interpreted and protested vehemently whenever the Federalists did more than the letter of the law allowed.

Details of the transaction arrived on President Jefferson’s desk in late June, and he released the great news to the nation in time to celebrate it on Independence Day. Although the president was thrilled to have obtained Louisiana, it went against his core principle that the powers authorized by the Constitution were limited to those expressly stated; there were no “implied powers” which allowed for the central government to do more as his political antagonist, Alexander Hamilton, and the Federalists had always argued.

But things look different when you are the president and, fortunately for the country, Jefferson was smart enough to recognize that expediency is sometimes the wisest policy. Accordingly, Livingston and Monroe were forgiven for exceeding their instructions, the money to pay for Louisiana was found by Albert Gallatin, the brilliant Treasury Secretary, and President Jefferson set his Constitutional convictions aside and asked Congress to approve the transaction.

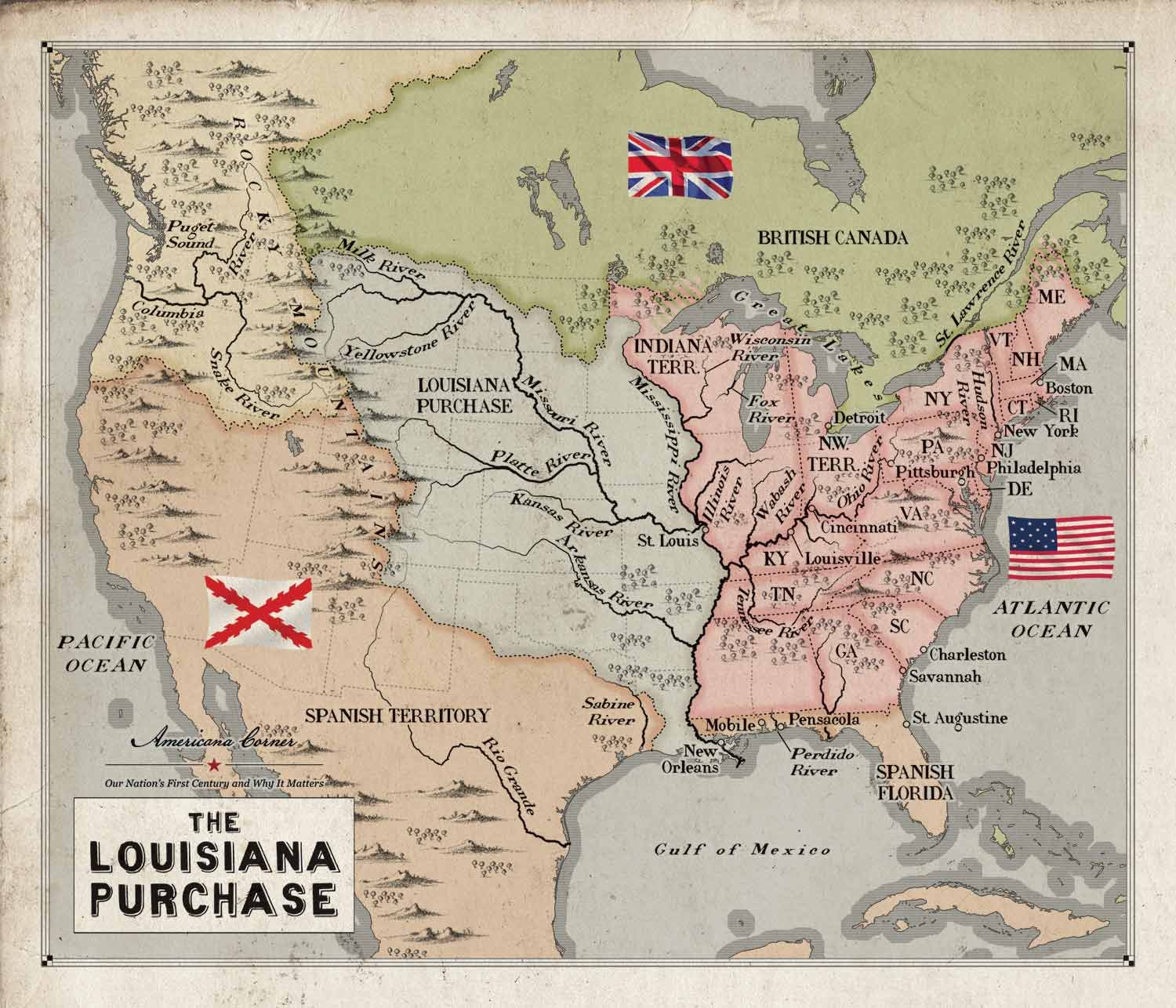

Surprisingly, this monumental issue languished for the rest of the summer, with seemingly no sense of urgency displayed by Congress for this deal of the century. Finally on October 17, the Senate took up the matter and three days later, on October 20, 1803, the purchase of Louisiana was ratified by a vote of 24 to 7. Thus, the nation was doubled in size, adding territory that would become the states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and parts of Minnesota, New Mexico, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. By this Olympian real estate transaction, the United States gained 828,000 square miles of virgin lands or more than half a billion acres, and all at the cost of roughly $.04 per acre. Looking back, it was the deal that made America.

The importance of the Louisiana Purchase was summed up by Henry Adams in his classic The History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. “Livingston had achieved the greatest diplomatic success recorded in American history. Neither Franklin, Jay, Gallatin, nor any other American diplomatist was so fortunate as Livingston for the immensity of his results compared to the paucity of his means. Other treaties of immense consequence have been signed by American representatives, the treaty of alliance with France; the treaty of peace with England which recognized independence; the treaty of Ghent; the treaty which ceded Florida; the Ashburton treaty; the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, but in none of these did the United States government get so much for so little.”

“The annexation of Louisiana was an event so portentous as to defy measurement; it gave a new face to politics, and ranked in historical importance next to the Declaration of Independence and the adoption of the Constitution, events of which it was logical outcome.”

Next week, we will discuss the start of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The midnight deal Robert Livingston, United States Minister to France, struck with Francois Barbe-Marbois, Napoleon’s Finance Minister, on April 13, 1803, to purchase the Louisiana territory was one of the most impactful agreements in the history of the United States. It resulted from months of conversations Livingston had had with numerous French officials, creating a foundation for the details that would follow. But as important as this step was, there remained several hurdles to overcome.