British Capture Savannah

In 1778, after three years of fighting their rebellious American colonists, the grand British Army was largely confined to New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. General George Washington’s Continental Army controlled virtually everything else as the hoped for Loyalist uprising in rural colonial America had failed to materialize. During this period, the British had focused their efforts on the northern colonies, basically from Pennsylvania north to New York, New England, and the Canadian border.

In 1776, Sir William Howe had driven General Washington out of New York and chased him across New Jersey, only to be thwarted by Washington’s brilliant stroke at Trenton and Princeton. The following year, British forces had tried to split the colonies in two during their Saratoga campaign, but the result was the humiliating surrender of General John Burgoyne and his entire army on October 17, 1777.

While Burgoyne was failing badly in upstate New York, General Howe had captured Philadelphia, the seat of the rebel government. However, these gains in Pennsylvania proved to be short-lived as France entered the war in 1778 and the British Army, now commanded by Sir Henry Clinton, was forced to evacuate Philadelphia, and return to New York to concentrate their forces.

Thus, thirty-eight months after the Battles of Lexington and Concord and repeated efforts in multiple states, the British Army was stymied in the north and seemingly no closer to defeating the upstart Americans. At this point, Lord George Germaine, the Secretary of State for the American Department, decided to make a strategic shift and focus his efforts southward starting in Georgia and South Carolina.

Although the British under Sir Henry Clinton had tried and failed to capture Charles Town, modern-day Charleston, in June 1776, they had made no concerted effort to establish dominion over the southern colonies since the start of the American Revolution. Even their garrison based at St. Augustine, just seventy miles from the border with Georgia, had been content to simply defend the colony of East Florida rather than initiate any offensive actions.

Germaine, who was under pressure by King George and Prime Minister Lord Frederick North to deliver some positive results, had been repeatedly approached by exiled American Loyalists living in London. They informed Germaine that the southern colonies of Georgia and the two Carolinas were heavily populated by Loyalists wanting to support the Crown and were simply waiting for assistance from the British army, and he decided to act on this advice.

George Romney. “Major-General Sir Archibald Campbell, 1790-1792.” National Gallery of Art.

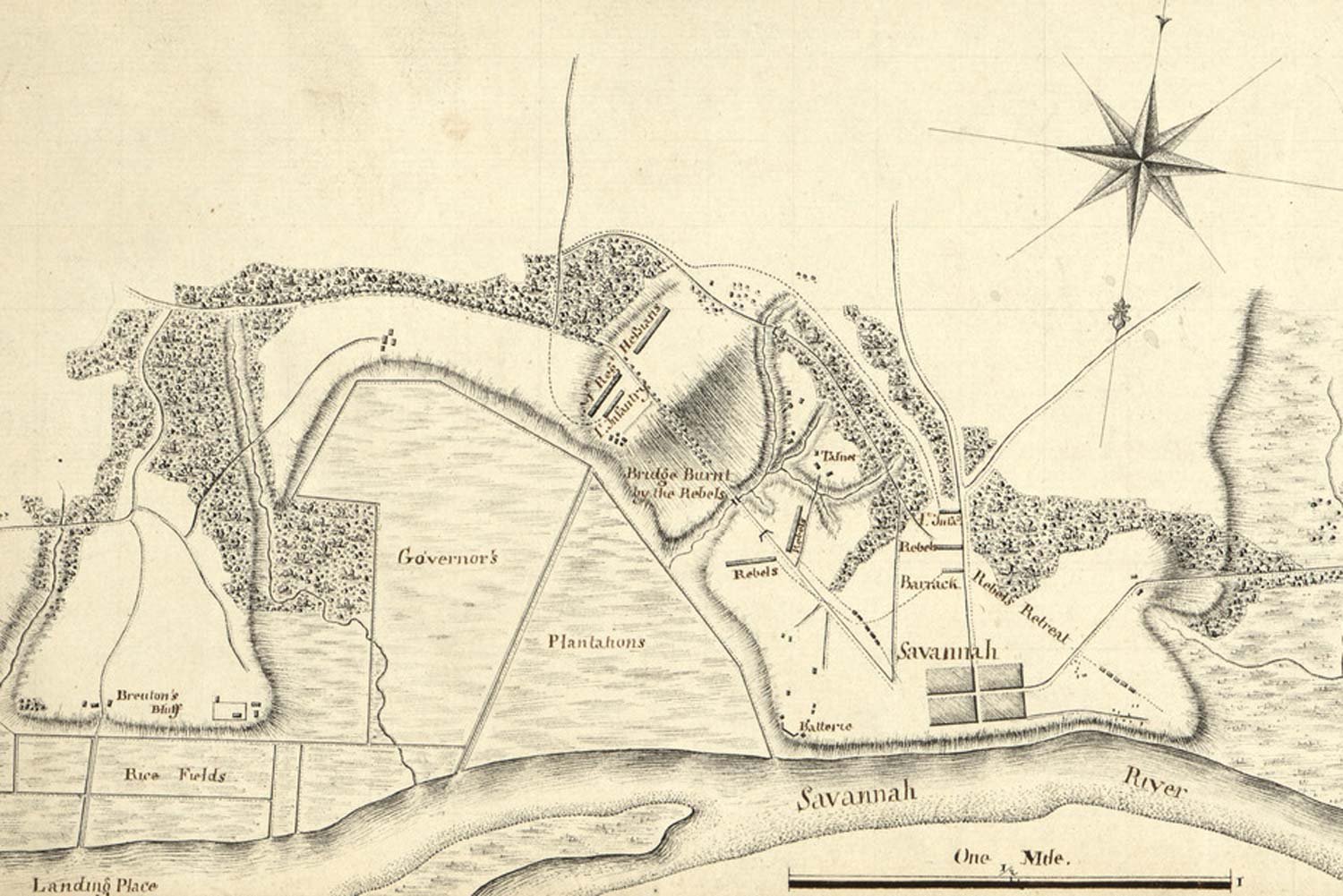

In December 1778, a British fleet landed 3,100 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell just south of Savannah, the colonial capital of Georgia. The city was garrisoned by a weak mixed force of local militia and a regiment of Continental soldiers, and it fell after a brief battle on December 29. While Campbell’s Redcoats suffered only 24 casualties, the Americans had over 500 men killed, wounded, or captured.

More importantly, with this victory, the British effectively gained control of most of the colony of Georgia. From this new base, Campbell hoped to move inland and stir the populace to join the British cause. But, contrary to their expectations, Loyalist sentiment was not as widespread as had been promised. Although Campbell successfully recruited some 1,000 men to his banner, there was no groundswell of support from the people of South Carolina.

There were a few minor engagements in Georgia and South Carolina in early 1779, most notably at Kettle Creek where Patriots under the leadership of Andrew Pickens scored their first victory in the backcountry of Georgia. Otherwise, the southern front was relatively quiet until October, 1779 when a combined American and French force led by French Admiral Comte d’Estaing attempted to take back Savannah.

This attack, launched on October 9, was an unmitigated disaster. D’Estaing’s efforts to reduce the fortifications by cannonade had been futile and, growing frustrated, he sent his men forward in a reckless assault against the entrenched Brits. In d’Estaing’s defense, he advanced side-by-side with his men, incurring two musket wounds. The losses incurred by the attacking allied force were horrific, approximately 1,000 men killed, wounded, or captured, while the British suffered just over 100 casualties. One notable death was that of Count Casimir Pulaski, a Polish nobleman who came to America in 1777 to help the American cause. Pulaski, a brave and daring Brigadier General, has been called the “Father of the American cavalry” for his work to improve the cavalry arm of the Continental Army.

Even more consequential than the battle losses were the contrasting manner in which the two adversaries viewed the results. The British, with Georgia now solidly in their control, decided they could move onto the next objective in their southern strategy, the South Carolina port city of Charleston.

On the other hand, d’Estaing’s missteps caused the Americans to lose some faith in their European ally. The defeat was the second failed American-French joint effort in as many attempts (the first being the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778).

Although the rank-and-file French soldiers were brave, their leadership seemed disorganized and arrogant. Certainly, the weapons and gunpowder supplied by the French were critical to our success. But more and more, it was becoming apparent that the Americans would have to depend on themselves for battlefield victories on their road to independence.

Next week, we will discuss the fall of Charleston. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.