History of the South Carolina Backcountry

Following General Benjamin Lincoln’s surrender of Charleston on May 12, 1780, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, offered a full parole to the captured Americans as long as they remained neutral. The other American garrisons in the state at Ninety Six, Camden, Beaufort, and Georgetown were extended these same terms.

Faced with choosing between retreating into the mountains and continuing the fight or agreeing to Clinton’s terms, most men accepted parole and returned home. With a large British army in the state and with very little to show for four years of resistance, most men felt the American cause was at an end and further resistance was futile.

Attitudes of the backcountry Patriots changed dramatically following two blunders by the English. First, on May 29, troopers from Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion allegedly murdered unarmed Patriots trying to surrender at the Battle of the Waxhaws. Then, on June 3, Clinton rescinded his parole terms to the American soldiers and demanded they swear an oath of loyalty to the British Crown.

These two events turned neutral observers of the war into angry men aching to get back at the Redcoats who had humiliated them. Over the course of the next few weeks, bands of armed backcountry men came together to resist the British occupation. These groups were generally mounted and mobile, and they knew the terrain over which they were fighting.

The success of British arms also emboldened Loyalists in the state, and many began to rally around the Union Jack. But more than wanting to defend King and Country, these Loyalists wanted to settle decades-old scores with their neighbors in this region that was rife with anger and differences ranging back to when the backcountry was first settled.

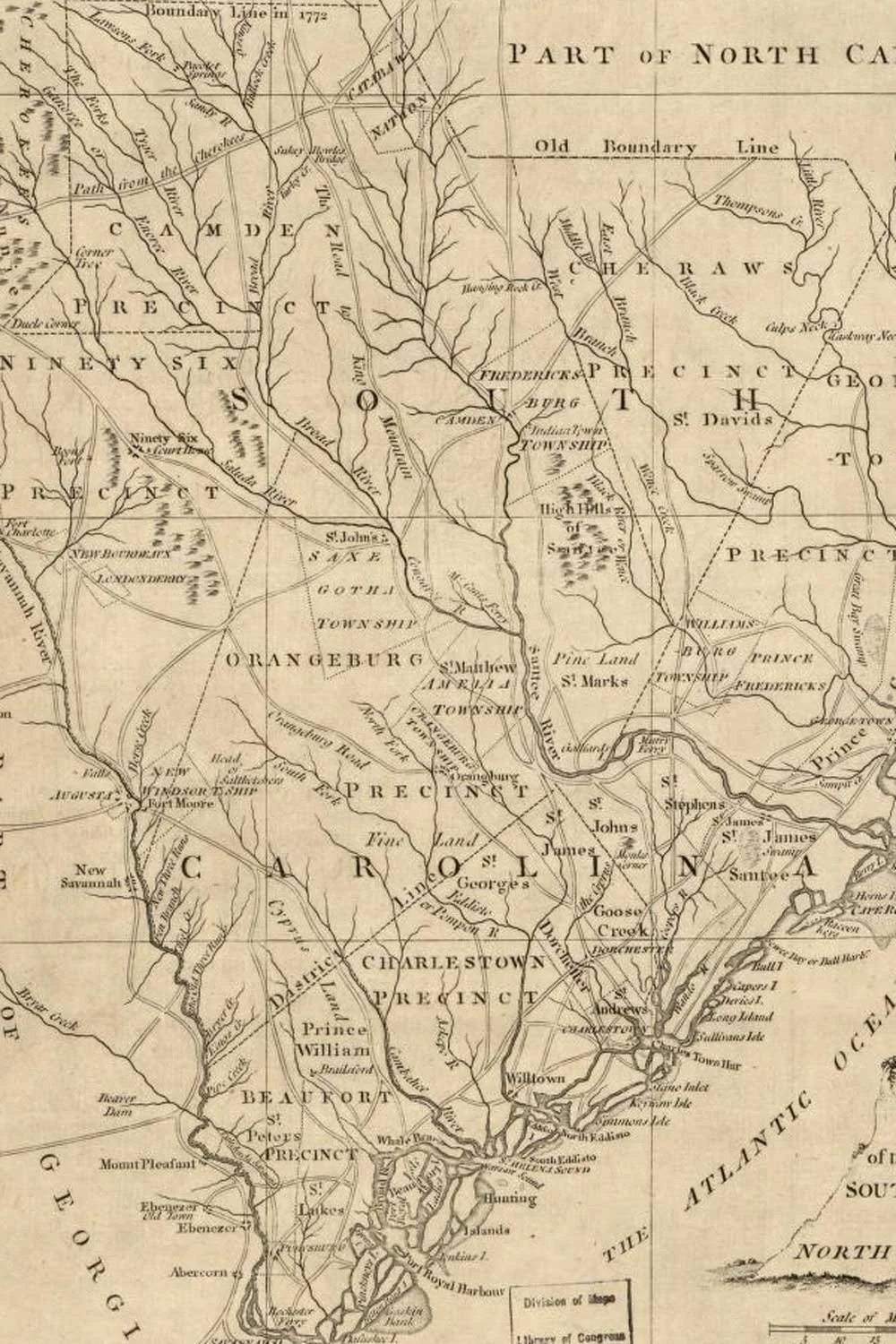

The backcountry of South Carolina, roughly defined as the area from about fifty miles inland all the way to the mountains, was practically unsettled by European-Americans until the middle of the 18th century. The populating of this section began in earnest in the 1740s when large numbers of Scots-Irish began immigrating there. Following the Great Wagon Road west from Philadelphia and then south from Harrisburg, these pioneers passed through Virginia and North Carolina before settling in South Carolina.

Not surprisingly, the primary draw to South Carolina was cheap, available land, and more of it than in the other southern colonies. In addition, the colony was known for its religious toleration, and it had a seaport in Charleston from which the settlers could ship the goods they produced. In 1740, almost no Euro-Americans lived in the backcountry, but by the start of the American Revolution this area was home to almost eighty percent of the colony’s white population.

“A new and accurate map of the province of South Carolina in North America.” Library of Congress.

Civil conflict and the bad blood it wrought had been boiling in the South Carolina backcountry for about two decades. In 1760, the Cherokee Indians had raided western settlements in retaliation for encroachments by American colonists. Settlers that did not flee the upcountry for Charleston were brutally murdered, and the Cherokee gained control of much of the colony. The Indians were finally subdued in 1761 and eventually moved to reservations further west.

In the wake of this conflict, a terrible lawlessness filled the region and organized, armed bands of outlaws replaced the predatory Indians. By 1766, these “undesirables,” who even coordinated with other gangs from as far away as Pennsylvania, controlled the area and terrorized the populace.

Pushed to the breaking point, the law-abiding settlers who hoped to build stable communities in the backcountry finally began to fight back in 1767. They adopted the name of Regulators and organized into their own bands and hunted down and killed the criminals in their hideouts. The fight turned particularly ugly, and terror was repaid with terror by both sides.

Sanctioned by the legislators in the Commons House in Charleston, the Regulators broke the back of the outlaw bands within six months, with most of the criminal leaders either being hanged or leaving the region. Not content with crushing the outlaws, the Regulators began to single out others they deemed “Rogues, and other idle, worthless, vagrant people.”

The Regulators wanted nothing less than total control of the backcountry, and, ironically, those that originally wanted law and order became the lawbreakers. Their cruelties led to a backlash against the movement and more bloodshed followed as groups calling themselves Moderators formed to resist the Regulators.

It was a case of neighbor aligned against neighbor and fractured whatever harmony had existed in the backcountry. In March 1769, each side assembled some 700 followers near the banks of the Saluda River and prepared to fight it out. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, and the men were convinced to disperse and let civil authority govern the district and punish any wrong-doers.

This episode was but a relatively gentle prelude to the terrible backcountry brawl of the 1780s. That one would see some of the most bitter and violent action of the American Revolution.

Next week, we will discuss North Carolina’s Regulator Insurrection. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.