Southern Continental Army Tries to Regroup Under General Gates

The surrender of Charleston and its entire 5,000-man garrison on May 12, 1780, essentially eliminated the American southern Continental Army. At that point, Lord Charles Cornwallis and his British legions were able to operate virtually unopposed in South Carolina.

To restore a presence in the state, Congress named General Horatio Gates, the victor of Saratoga, as the new southern commander. General George Washington knew Gates well and recognized this was a bad decision but being the good soldier and always deferential to political authority, Washington accepted it.

Gates had a checkered past in the Continental Army. In late 1777, following his success at Saratoga and coupled with Washington’s loss of Philadelphia, Gates joined with a small group of Continental Army officers in an effort to undermine Washington and convince Congress to replace him with Gates. Led by Brigadier General Thomas Conway, this intrigue, known as the Conway Cabal, was discovered and thwarted.

Gates apologized to Washington for his role in the affair but was shunted off to a staff position. Aching for another command, Gates saw his opportunity when Charleston fell to the British. The ever-political Gates lobbied for the now open southern command and his allies in Congress gave him the assignment. Gates headed south from Traveler’s Rest, his home near present-day Shepherdstown, West Virginia, arriving at the American base camp at Buffalo Ford on the Deep River in North Carolina in late July.

Here, Gates found a small but well-trained group of Continental soldiers under the leadership of Major General Baron Johannes de Kalb, a Frenchman who had been fighting for the American cause since 1777. The fifty-nine-year-old De Kalb, who was better conditioned than men half his age, was arguably the most capable of the foreign officers fighting on the American side, having served France for almost forty years.

This small army was comprised of about 1,400 Continentals from some of the army’s best regiments, veteran fighting men from Delaware and Maryland. They were also some of the best led with officers such as Maryland’s Lieutenant Colonel John Eager Howard who Major General Nathanael Greene said was as “good an officer as the world affords” and Colonel Otho Holland Williams, the regiment’s Adjutant General.

Interestingly, the Delaware Regiment that was present was the only one raised by the state during the American Revolution. Delaware, the smallest of the thirteen colonies, focused on quality rather than quantity when it came to raising troops. It was generally regarded as the best trained, best equipped, and best fed regiment of the Continental line.

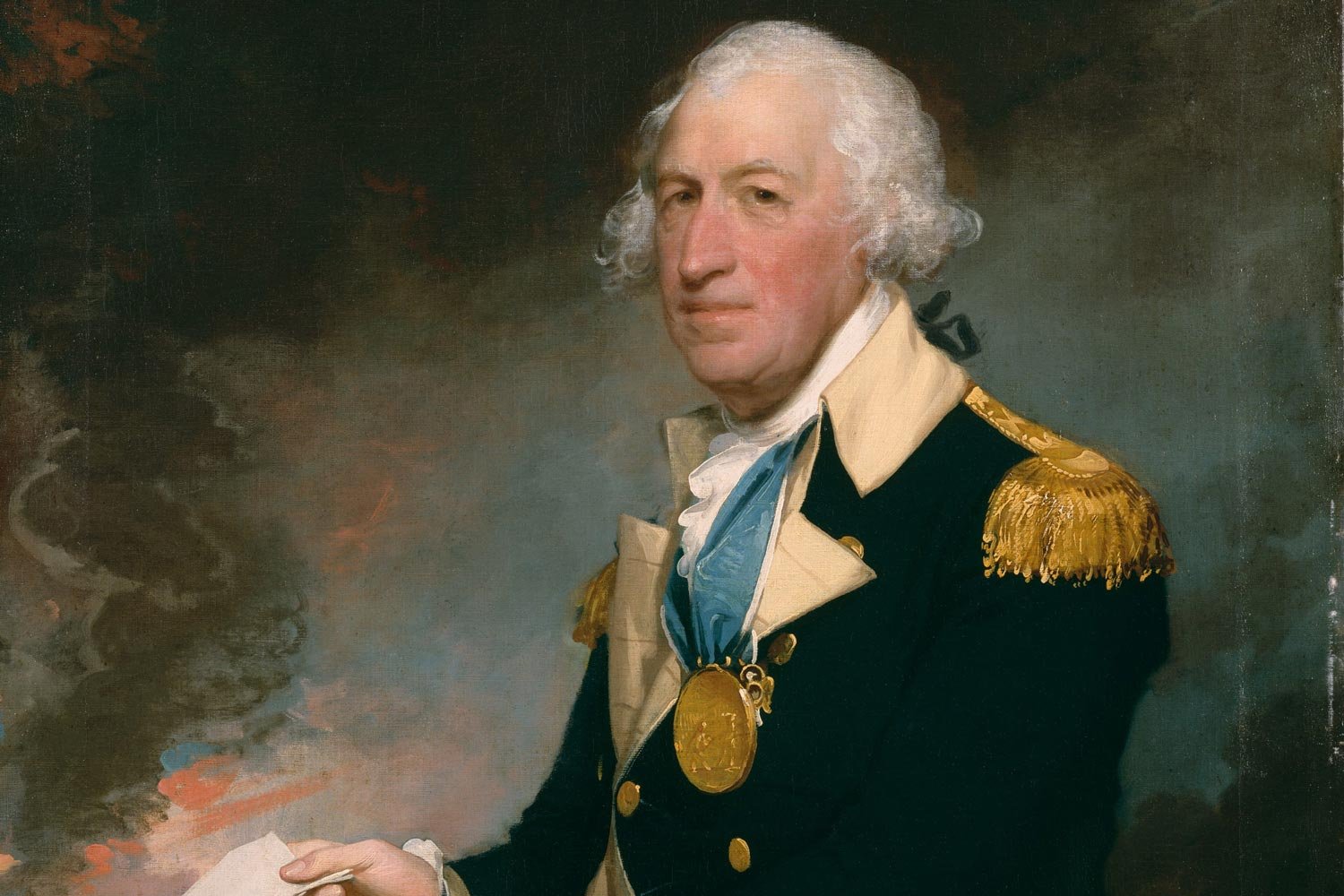

“Maj. Gen. the Baron de Kalb.” The New York Public Library.

De Kalb’s detachment was originally sent to the Carolinas by General Washington for the relief of Charleston, but halted enroute when they received word of the city’s fall. De Kalb, knowing he must preserve his army above all else, then proceeded cautiously hoping to avoid a pitched battle with Cornwallis until his ranks were strengthened by militiamen promised by North Carolina and Virginia. With his army starving and few provisions to be found, De Kalb set up camp at Deep River waiting for reinforcements and supplies to catch up. It was here Gates found him and his hungry men.

Gates was anxious to strike the Brits at their base in Camden and, the next day, convened a council of war on how to best proceed. He was advised by the Continental Army officers and veteran South Carolinians like Francis Marion and Thomas Sumter to take a longer path through Salisbury and Charlotte which were rebel-held and where supplies were more plentiful. Instead, Gates chose to ignore this advice, and, on July 27, he led his men down the more direct road despite the scarcity of food to be found in that region.

One of Gates’s reasons for taking this route was to sooner effect a junction of his command with an estimated 3,500 North Carolina militiamen operating in the state. On August 7, at Mask’s Ferry, Gates found this band of North Carolinians under the command of General Richard Caswell, the three-time governor of the state. Unfortunately, there turned out to be only 1,400 militiamen and practically none of them had ever fired a shot in battle.

The march south continued with Gates’ troops marching into Rugeley’s Mills, about thirteen miles north of Camden, on August 13. By now, the Continentals were exhausted, having marched for seventeen straight days with little food to eat. One Delaware sergeant noted that during the march they had subsisted on one half pound of flour each day, “living chiefly on green apples and peaches.”

The next day, Gates’s army was joined by 700 Virginia militiamen who were equally tired and hungry and who, like the North Carolina militiamen, were preparing to face the enemy for the first time. So now Gates had his full complement of soldiers assembled, roughly 1,400 veteran Continentals and 2,100 untrained and unproven militiamen, to do battle with the British.

Meanwhile, just down the road in Camden, Lord Cornwallis had under his command 2,300 of the best trained and most experienced Redcoats in North America. Within two days, the armies would square off with disastrous results for the American cause.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Camden. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.