The Battle of Blue Licks

The American Revolution was winding down in the second half of 1782, with peace negotiations being conducted in earnest in Europe. But those talks appeared to have little impact on the actions of the main antagonists west of the Appalachians, as both sides were preparing invasions to punish their adversary.

Captain William Caldwell led three hundred native warriors, Shawnee, Delaware, and Wyandot, across the Ohio to attack Bryan’s Station, a fortified settlement located in present day Lexington. The Kentuckians were alerted to the pending danger, and all took refuge inside the fort. Caldwell’s men, who reached Bryan’s Station on August 15, could do little against the palisaded walls of the stockade and withdrew two days later when they learned a relief force of 200 Kentucky militiamen led by Colonel John Todd and Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Boone was on its way.

Caldwell headed north towards the Ohio and safety with a 40-mile lead on the militiamen. After arriving at Bryan’s Station, Boone advised waiting for a force of several hundred Lincoln County militiamen led by Colonel Benjamin Logan to join them before beginning their pursuit. Unfortunately, less cautious men urged that they push forward, and Boone felt compelled to go along.

On August 19, the Kentuckians reached a crossing on the Licking River known as Lower Blue Licks, named for the ground turned grayish blue from the salt and mineral deposits that animals came to lick. Before fording the river, Indians were seen lounging on a hilltop on the other side, a sure sign of ambush. Colonel Todd asked Boone, the most experienced woodsman in Kentucky, what he recommended.

Boone told Todd, “They wish to entice us into an ambush” and noted how the retreating Indians were “concealing their numbers by treading in each other’s tracks” and yet they littered their trail with debris as if they wanted to be followed. The consensus among the officers was for waiting for Logan’s men to catch up before engaging the Indians.

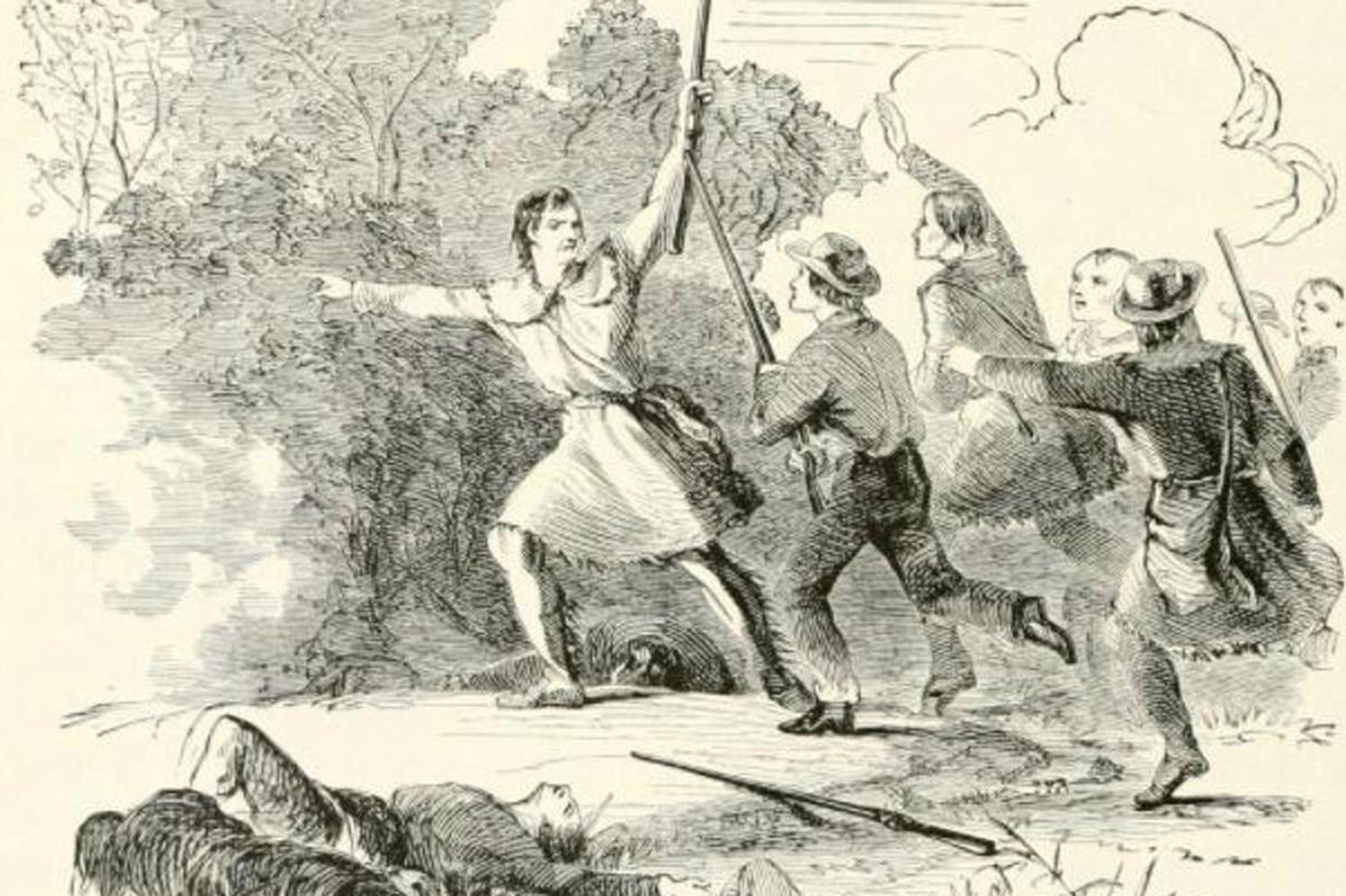

At that point, a hotheaded Major named Hugh McGary turned on Boone and said, “I never saw any signs of cowardice about you before.” Boone was enraged to the point of tears and shouted, “I can go as far in an Indian fight as any other man.” McGary then jumped on his horse, dashed into the stream brandishing his sword, and yelled for all to hear, “Them that ain’t cowards follow me.”

Keep in mind, these men lived in an age and an environment in which cowardice was a greater sin than foolishness, and calling someone a coward was tantamount to asking for a duel in refined society and a brawl to the death on the frontier. McGary’s company from Harrodsburg mounted up and raced after their leader, and the rest of the Kentuckians, swept up in the excitement, soon followed as well. As Boone led his company forward, he told them, “Come on, we are all slaughtered men.”

Boone was right; the Indians were waiting in a well laid ambush in the ravines across the Licking River, and when they opened up, their fire was devastating. Within the first five minutes, over forty militiamen lay dead or dying, including fifteen of the twenty-four officers, all easy targets mounted on their horses. Their accurate fire immediately broke the charge of the Kentuckians, and the fighting soon became a hand-to-hand melee with only Boone’s company continuing to advance.

McGary, the man responsible for the disaster, somehow escaped injury and raced to the rear as fast as his horse could carry him, telling Boone to retreat as well. Boone pulled his men together and headed back towards the Licking River which was now filled with the floating bodies of dead Kentuckians. Boone found a horse and ordered his son Israel to mount and get away from the carnage. In a matter of seconds, Israel was shot from the horse and died in his father’s arms.

“Benjamin Harrison.” Wikimedia.

The Battle of Blue Licks was the final large engagement of the American Revolution, and the greatest defeat suffered by Americans west of the Appalachians during the war. Poor battlefield leadership led to the disaster, but many in Kentucky blamed Colonel George Rogers Clark who was not even close to the scene, but rather at Fort Nelson, one hundred miles to the west.

One of those blaming Clark was Virginia Governor Benjamin Harrison who criticized Clark for failing to follow his orders and construct and man three forts along the Ohio, including one near the Licking River. While the criticism was valid, Harrison was also the man who failed to provide the funds to construct these forts. There were also growing rumors that Clark had taken to the bottle and was often drunk and incapable of performing his duties.

In any event, Clark hustled east and assembled 1,100 militiamen for another punitive strike on Indian villages north of the Ohio. They crossed into Shawnee territory on November 2, 1782, and campaigned for three weeks. The raid was a complete success with Clark’s men destroying six villages and a British trading post, as well as 10,000 bushels of corn, but it was largely unopposed, and Clark’s army only killed about twenty warriors.

Strategically, it finally forced the Shawnee to relocate further north and permanently abandon the villages closest to Kentucky, rendering future raids more difficult. Clark was once again a hero and even Governor Harrison sent a congratulatory letter stating, “the officers and men under your command deserve the highest praise from your country.” But it would prove to be the last hurrah for this devoted Patriot.

Next week, we will discuss the later years of George Rogers Clark. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.