The Legacy of George Rogers Clark

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution and granting independence to the United States of America. Perhaps more importantly for the settlers in Kentucky, the treaty brought an end to the steady stream of English guns and gunpowder to the Indians that had relentlessly attacked Kentucky during the war. That is not to say the danger from Indian attacks was completely over because old habits and hatreds die hard, and the Shawnee and Delaware were no exception to this rule; but at least with the peace came a temporary respite.

From 1775-1782, 860 Kentuckians were killed in countless fights and skirmishes, proportionally the greatest loss of life of any region in the American Revolution. While an average of ten people died for every 1,000 persons in the thirteen colonies, in Kentucky seventy died per 1,000 residents.

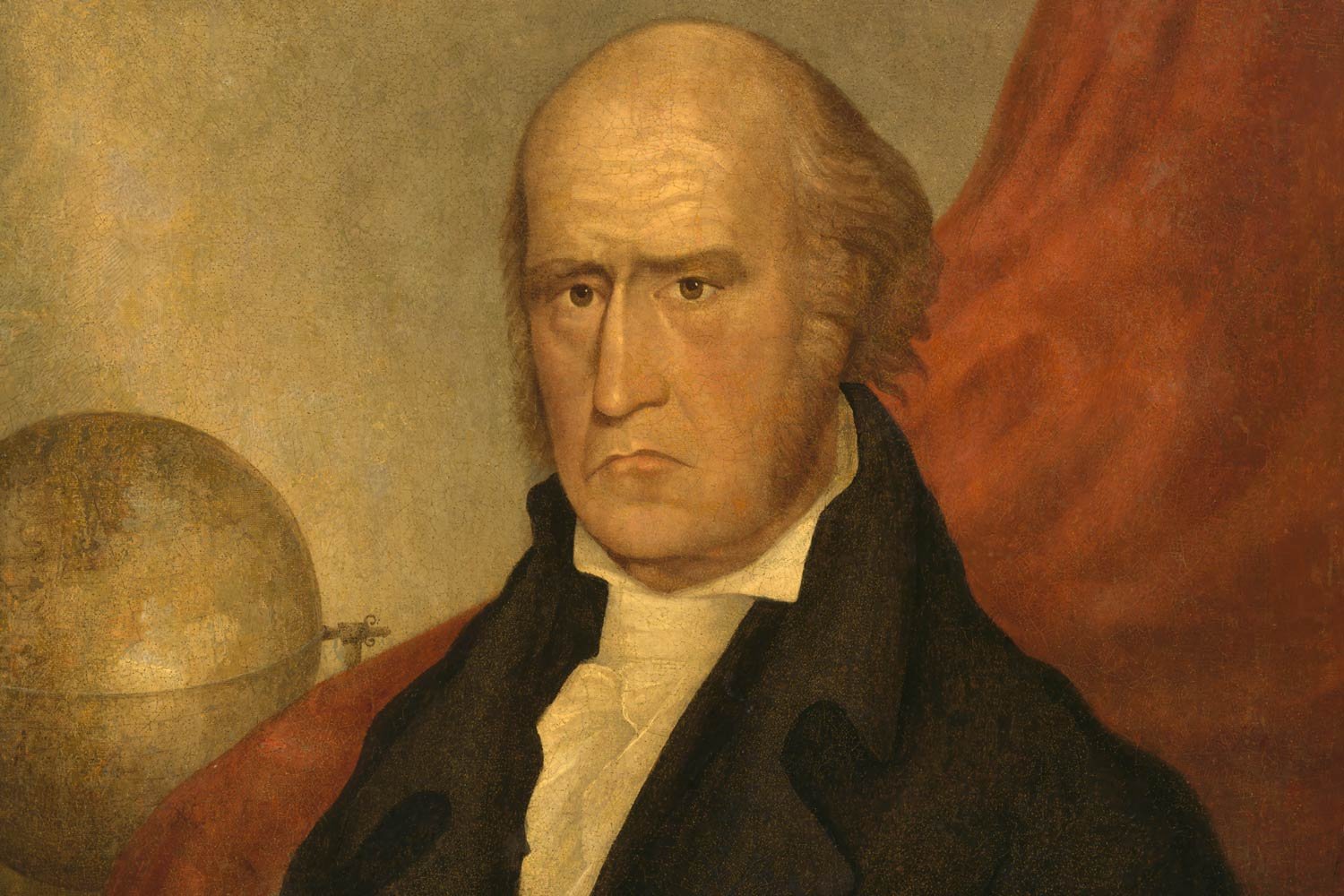

George Rogers Clark was only thirty when the Treaty of Paris was signed, and he had to figure out what to do with the rest of his life. For the man who had conquered what would become the Northwest Territory, finding a suitable encore would prove to be elusive. He did lead one last expedition against the Indian tribes in the Ohio Valley in 1786, but it accomplished very little.

Eventually, Clark turned to surveying and made a modest living, but he was dogged by creditors for the rest of his life. By the time of his death, Clark, who had been the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, retained only a small plot in Clarksville. The rest had all been taken from him to pay the debts he incurred purchasing supplies to win the war, debts for which Congress refused to reimburse him.

Simply based on results, George Rogers Clark must be ranked as the most successful American field commander of the American Revolution. Clark was never bested on the battlefield or ever failed to accomplish whatever military mission he started. No other American commander can make that claim, not Washington or Arnold or Greene.

Moreover, Clark displayed his military talents in multiple and diverse situations and against several renowned soldiers. Clark captured Fort Sackville without artillery support and defended by a veteran British officer, Major Henry Hamilton, in 1779. Clark defeated one of the great partisan leaders of the war, Simon Girty, fighting on Girty’s own turf in the largest pitched battle of the war in the west, the Battle of Piqua in August 1780. And he ambushed and defeated the renowned cavalry commander Colonel John Simcoe in a fight to defend Richmond in January 1781.

“The Northwest Territory.” Americana Corner.

Clark also led men on perilous, heroic marches like the 300-mile quest to take the far western British outposts of Kaskaskia and Cahonkia 1778, and again on a desperate 200-mile trek across a trackless flooded plain in the dead of winter to capture Vincennes in February 1779. Then, for three successive years (1780, 1781, and 1782), Clark led successful punitive raids on Shawnee villages that eventually broke the Indians’ will and their capacity to fight.

Such was his reputation among the natives that often warriors on a raiding mission returned home rather than face Clark in a fight. Clark was viewed with this same aura of invincibility by his fellow Kentuckians as well, and many men only joined expeditions if Clark was the commander.

Through sheer will and a leadership ability that was God given, Clark held his underfed, undersupplied, and undermanned armies together to accomplish so much for his country; and he did all this before turning thirty.

Sadly, following the war, as disappointment built on disappointment, Clark turned from the country he had fought so hard to defend. In the late 1780s, when Congress seemed to care little about forcing Spain to keep the Mississippi open for western goods, Clark talked with Spanish officials about serving them and even bringing Kentucky into their fold.

Then, in 1793, at the height of the French revolution, Clark accepted a Major General’s commission in the French army with the title “Commander in Chief of the French Revolutionary Legion of the Mississippi” from the French agent, Citizen Edmund Genet. While these intrigues never amounted to anything, they forever sullied his reputation, the commodity upon which he placed the most value.

So why should George Rogers Clark matter to us today? Whatever Clark became in his troubled later years, his accomplishments for his country during the American Revolution cannot be diminished.

Clark’s blend of military genius and unrelenting perseverance allowed him to take and hold a vast area comprising 300,000 square miles, land which later became our Northwest Territory, out of which five states (Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin), and part of a sixth (Minnesota) would be created. Only the Louisiana Purchase and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ending the Mexican War added more land to our nation.

Only George Rogers Clark had that rare combination of vision and charismatic leadership required to convince political leaders to support his audacious plans and the personal courage and hardiness needed inspire backwoodsmen to follow him to the end of the earth and make his dream a reality.

We must not forget that during his time in the sun, George Rogers Clark accomplished remarkable things for the country that he loved.

Next week, we will discuss Spain’s role in conquering the West. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the American Revolution, brought the United States its long-desired liberty and independence from Great Britain. But with that separation came the loss of protection on the high seas for American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. And the removal of that security blanket had painful and expensive consequences for the young country which were first felt several thousand miles away, in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.