British Outposts Fall During Pontiac’s Rebellion

In mid-May 1763, Pontiac attacked Fort Detroit and initiated his grand plan to drive the British from the Great Lakes. Word soon spread to Indian villages across the region and other tribes soon followed suit. By the time Pontiac’s Rebellion ended in 1765, it would be the deadliest Indian uprising ever in North America.

On May 16, several Wyandots approached Fort Sandusky on the south shore of Lake Erie and asked to speak with the commandant, Ensign Paully, with whom they were on friendly terms. Paully had the gates opened to admit the Indians and, while the chiefs were smoking a peace pipe with Paully, other Wyandot warriors massacred the fifteen man garrison. Paully was kept alive and given to an old withered Indian woman whose husband had recently died. It is hard to say who suffered more, the dead soldiers or Paully, but eventually Paully escaped and made his way back to Fort Detroit.

A similar story unfolded on May 25 at Fort St. Joseph in present day Niles, Michigan when a band of Potawatomis, under the pretense of visiting relatives in the fort, suddenly seized and slaughtered fourteen soldiers of the garrison. Two days later, Fort Miami, at the head of the Maumee River, was taken when natives lured Ensign Holmes, the commander, out of the fort on a mission of mercy to help an ailing Indian woman. Once in their village, they murdered Holmes, cut off his head, and tossed it into the fort. The now leaderless nine-man garrison surrendered.

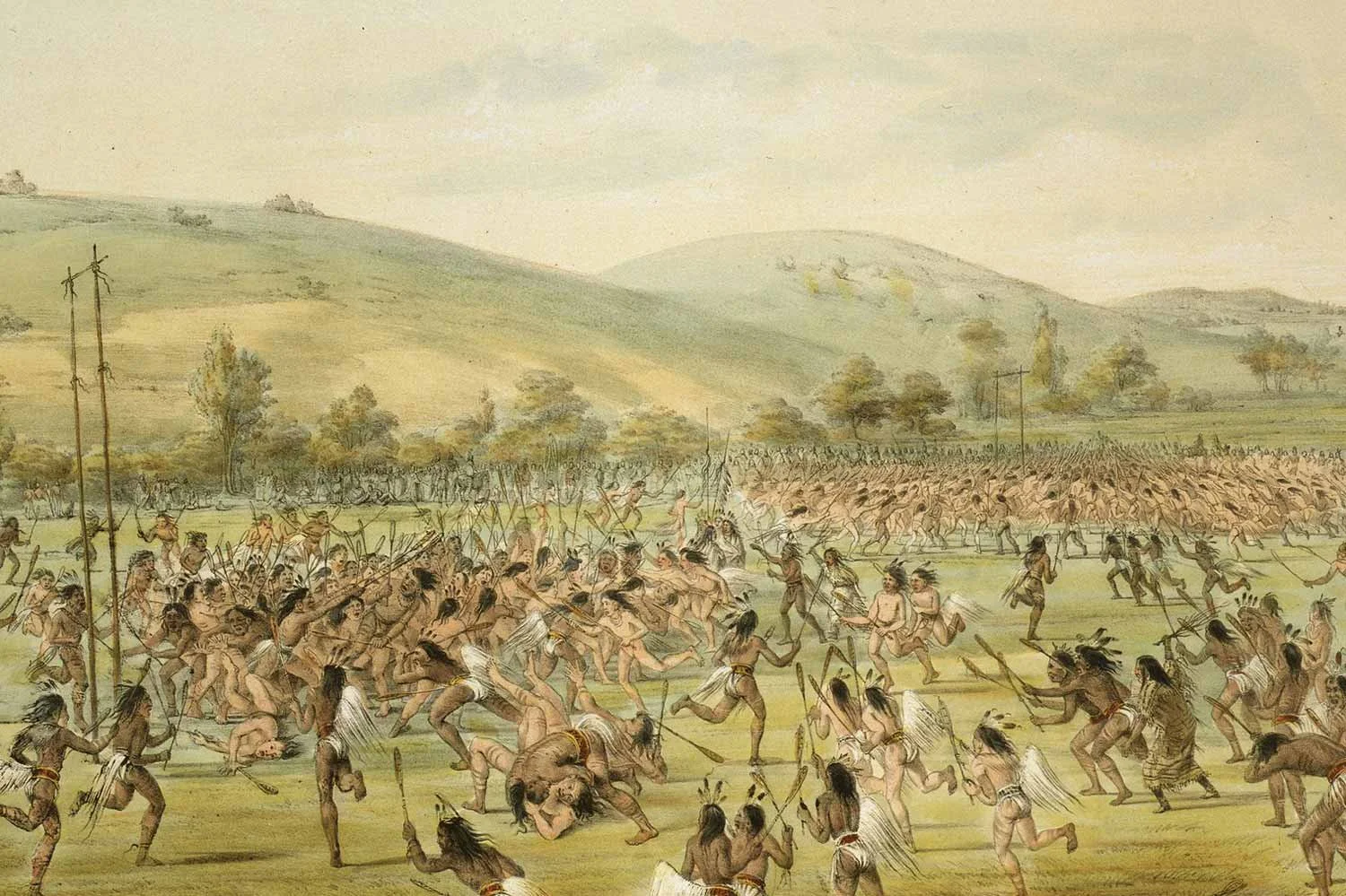

The following week, Fort Quiatenon, in present day Lafayette, Indiana, was captured by a band of Kickapoos and, on June 4, Fort Michilimackinac at the beautiful Straits of Mackinac, the most remote British outpost, was taken by surprise. This site, originally established by French Jesuits in 1671, was home to thirty-five British soldiers and a few dozen traders. Ojibwas (Chippewas) organized a game of baggataway (the precursor to lacrosse) against a tribe of Sauks, as they had done many times before. The field of play was immediately in front of Fort Michilimackinac and involved hundreds of braves from each tribe racing to and fro and screaming like banshees as they pursued the ball.

Some of the chiefs invited the commander, Captain Etherington, to watch their match just in front of the main gate, which he did, and Etherington allowed his thirty-five troops to do the same. Etherington, despite being forewarned that the Ojibwa were planning to strike the British at some point, did not think it necessary to have the men armed.

George Catlin. “Ball Play.” Library of Congress

Numerous Indian women, wrapped in blankets, congregated near the opening to the fort and around the field of play. At a signal from the head warrior, the ball was thrown near the gate and the hundreds of native players suddenly raced towards the gate, stopping long enough to grab tomahawks that the Indian women had hidden beneath their blankets.

Within seconds, the Indian braves were inside the fort and the slaughter began. Most of the soldiers and traders quickly surrendered, but the warriors still killed fifteen of the soldiers and many more traders, taking twenty men, including Etherington, as captives. About a week later, a war chief who had missed out on the attack entered the makeshift prison and killed seven of the Englishmen with his knife. Later that night, the bodies were boiled and eaten at a feast held by the Indians.

With the fall of Fort Michilimackinac, except for the besieged garrison at Fort Detroit, the entire Great Lakes territory was devoid of British troops. Two weeks later, a second wave of attacks against British forts began in the upper Ohio Country, stretching from Fort Pitt and to Lake Erie.

The first to fall was Fort Venango on the Allegany River, near present-day Franklin, Pennsylvania, on June 16 to a band of Senecas who gained entrance to the fort by professing their friendship for the Englishmen. They immediately killed the twelve-man garrison but kept alive the commander, Lieutenant Gordon, so he could write a letter to British officials outlining the Native’s complaints. Once that was completed, they burned Gordon alive over the course of several days, stopping each day just in time to prevent Gordon from dying too soon and spoiling their entertainment.

On June 18, another band of Senecas moved north and took Fort Le Boeuf, located at a portage site that connected Lake Erie with the Allegany River, but the twelve-man garrison escaped by cutting through the back wall. The next day, June 19, the eighth and final British fort to fall, Fort Presque Isle, near present-day Erie, Pennsylvania, surrendered to a mixed group of Ottawas, Ojibwas, Wyandots, and Senecas after a three-day fight. The thirty soldiers that survived the fight were marched to Detroit and later used in prisoner exchanges. Although no more British outposts would be lost to the Indian onslaught, the fighting was far from over.

Next week, we will discuss Pontiac’s Rebellion moving east. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.