Pontiac’s War Moves East

With the forts around the Great Lakes taken by early June 1763, Pontiac’s Rebellion moved east towards the remaining British outposts along the frontier and the settlements just beyond. The following months would bring unprecedented bloodshed to American colonists, with long term consequences to colonial expansion plans.

The British American frontier in 1763 did not extend beyond the Allegheny Mountains, but rather ran in a line roughly from mid-state New York at German Flats along the Mohawk River to Bedford in present-day south central Pennsylvania. Further south into Virginia, settlements were also compressed along the eastern seaboard, east of the lower Appalachian range.

The keystone fort in this region of British America was Fort Pitt at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers where they form the mighty Ohio River in present-day Pittsburgh. Fort Pitt, built in 1759 by General John Stanwix, was an impressive structure, with corner bastions holding sixteen cannons and ramparts of earth faced with brick overlooking the Ohio. Its commander was Captain Simeon Ecuyer, a Swiss mercenary, who led 230 men, roughly half British regulars and half local militia.

But it was an isolated outpost, almost sixty miles away from the small garrison at Fort Ligonier and then another forty miles from Fort Bedford. After that, it was one hundred miles to Carlisle, the Susquehanna River, and the settlements beyond. If trouble came, Fort Pitt would be on its own until help could arrive from New York or Philadelphia.

Delaware and Shawnee warriors made their initial incursions in late May against the defenseless farms scattered throughout the area, killing all colonists they could find. Those settlers that survived fled to the relative safety of Fort Pitt. On June 22, the Indians first fired on the fort, but it was more of an announcement of their hostile intentions than an assault.

The next morning, a contingent of chiefs, led by Turtle’s Heart, appeared at the gate professing their friendship for the Brits. The chief told Captain Ecuyer “there were bad Indians already here; but we will protect you from them.” Ecuyer must have chuckled to himself as he told Turtle’s Heart “we are grateful for your kindness” …but “we mean to stay right here.” Their ruse failing, the angry Delawares and Shawnees withdrew from the fort and, for the next several weeks, effectively laid siege to Fort Pitt while they continued their attacks across the frontier.

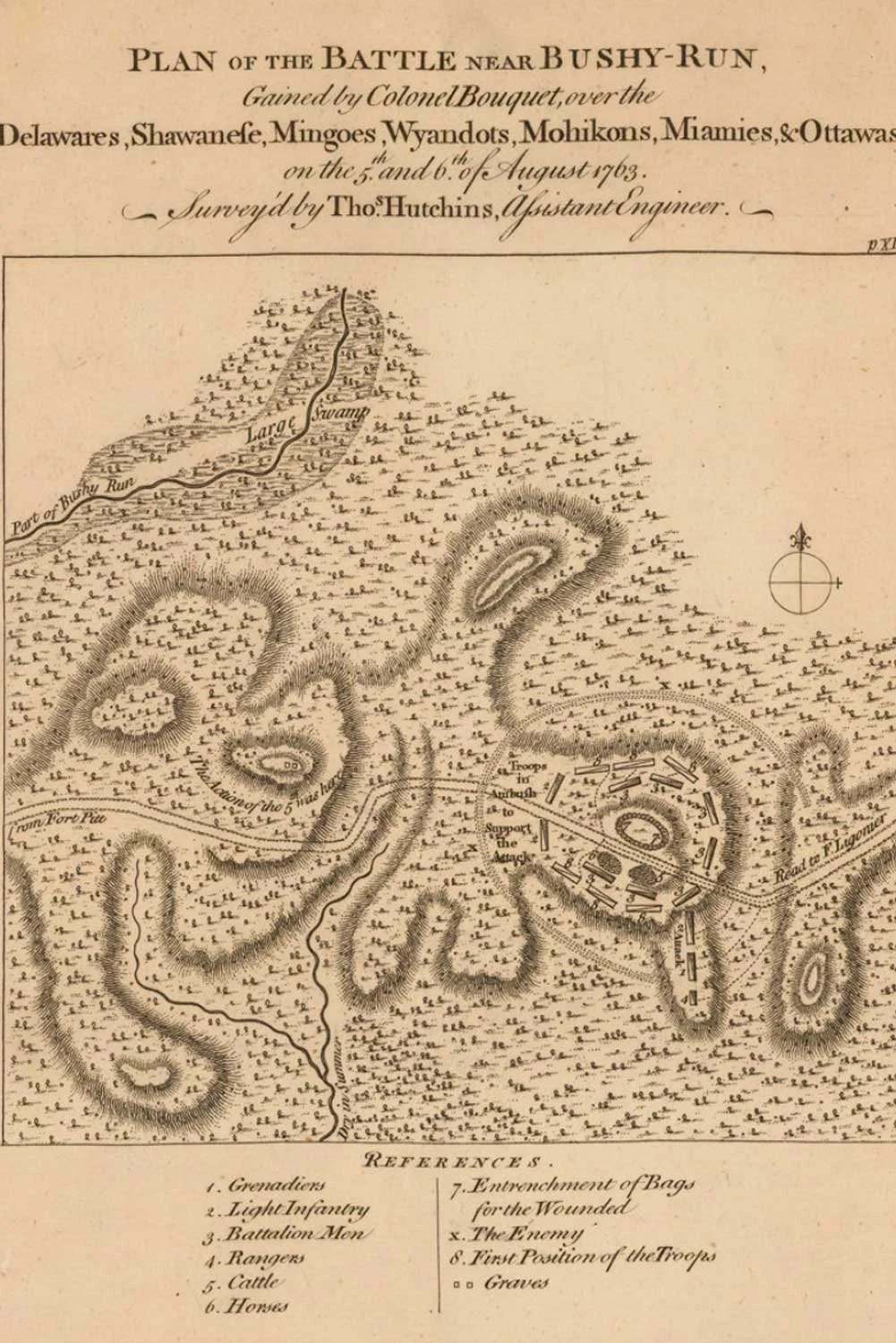

In early August, the natives unexpectedly moved away from the fort to attack a 500-man relief force led by Colonel Henry Bouquet. On August 5-6, a fierce fight, the Battle of Bushy Run, took place in the dense forest about twenty five miles east of Fort Pitt. Although severely pressed by the Delaware and Shawnee warriors, Bouquet's troops survived the initial onslaught and routed the native warriors. Four days later, Bouquet reached Fort Pitt, ending the siege and rendering Fort Pitt unassailable, but the carnage throughout western Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia was far from over.

“Plan of the battle near Bushy Run.” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

Into the fall of 1763, all along the entire frontier, Indian bands roamed practically at will, burning crops and farms, destroying livestock, and killing any colonist they could find. Among the first groups murdered were the traders who had lived with the Native Americans for years, bringing them much needed iron tools and other supplies in return for furs. These traders made easy targets for Indian warriors seeking any European scalp they could find, and it is estimated well over a hundred of them met their fate during this time.

Terror reigned supreme throughout the region, and, by the end of 1763, more than one thousand families had fled east trying to escape the wrath of the Indians; the condition of the refugees was beyond wretched. In the words of one contemporary, “the miseries and distresses of the poor people were really shocking to humanity…And on both sides of the Susquehanna, for some miles, the woods were filled with poor families, and their cattle, who make fires, and live like the savages.” Although armed bands of colonists went in search of the war parties, they were no match for the Indians who simply melted away into the vast wilderness.

In one gruesome episode, three or four Delaware natives approached the fortified home of Archibald Glendenning in the small village of Greenbrier in present-day West Virginia. Having been on friendly terms with them for a long time, the Indians were admitted into the home, and offered an elk carcass for their feast.

Soon, other braves emerged from the woods and asked for admission as well. Not wanting to insult them, they were allowed in. An old woman asked one of the Indians if he knew a cure for a cut she had recently received, and he responded by splitting her skull with a tomahawk, not exactly your standard remedy. At that signal, a general slaughter began, and most of the one hundred colonists were either murdered or taken captive.

By the fall, a requisition had been made by British authorities to several colonies for them to supply men for a spring offensive. The year 1764 would see the wrath of the colonies descend on Pontiac’s troublesome confederates.

Next week, we will discuss the British taking back the Great Lakes. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.