George Rogers Clark Leads Invasion of Illinois Country

As the American Revolution continued in the east, the British removed all regular troops from their western outposts to assist in the more active theater. Naturally, that exposed a weakness in their defense, one that the intrepid George Rogers Clark would soon exploit with an invasion of the southwestern region of the Province of Quebec. The results of this conquest would be felt several years later when this land captured by Clark was granted to the United States by the Treaty of Paris.

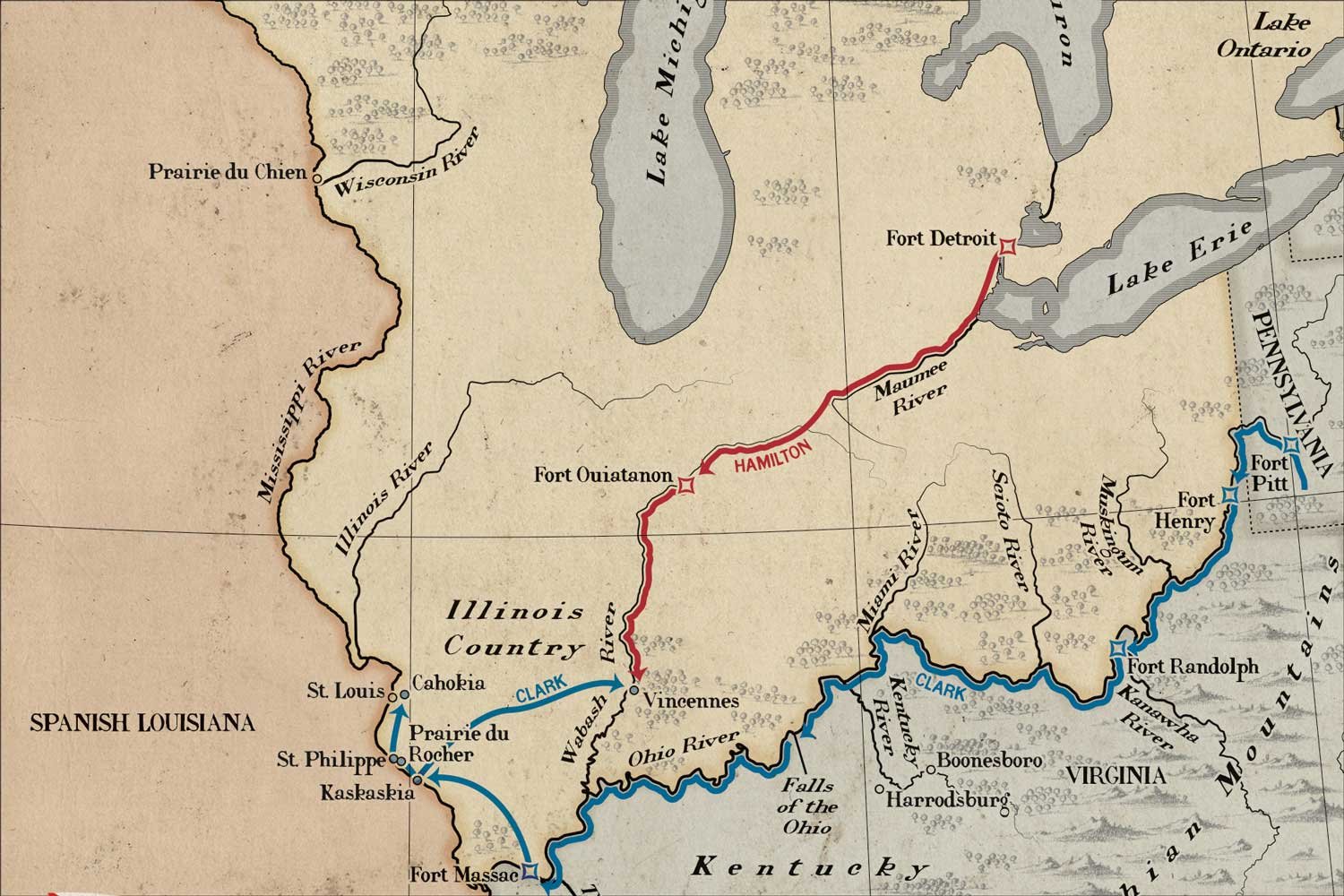

Clark conceived an audacious plan to take a body of men down the Ohio River, land just south of the far western British outposts of Kaskaskia and Cahokia and take the two forts by surprise. Given the logistics involved and the number of able bodied men required to make this dream a reality, Clark needed the support of the Virginia Governor and Assembly. Hence, after the Indian raiding season ended (and yes, there was a season for these raids as the Indians rarely ventured out in the winter), Clark hustled back east to Williamsburg.

On December 10, 1777, Clark presented his scheme to Governor Patrick Henry and the executive council of Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and George Wythe. Besides taking British territory, Clark argued the conquest of the two Mississippi Valley forts would open a conduit to the Americans of badly needed supplies from the Spanish just across the Mississippi at St. Louis and further south in New Orleans. In early January 1778, Governor Henry and the executive council approved Clark’s proposal, named the twenty-five year old Clark as the expedition’s commander (promoting Clark to Lieutenant Colonel), and authorized him to raise an army of 350 men.

“Patrick Henry.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Clark soon discovered being authorized to raise an army was easier than actually doing so. After three years of war without much progress being made, enthusiasm for joining the army was fairly low. To make matters worse, the constant threat of Indian raids in Kentucky and Tennessee caused most men west of the Appalachians to feel they should remain close to home rather than venturing away from the area.

When Clark assembled his contingent at the Falls of the Ohio (present-day Louisville), there were only 178 men on hand, about half of what had been planned. Most were untrained militiamen with little or no formal military training. Although they were not uniformly dressed or equipped and possessed no artillery pieces, this hardy band would demonstrate that their fortitude and courage would more than make up for any of these deficiencies. Fully understanding that an undersized group of determined men, well led, could accomplish oversized deeds, Clark broke camp on June 24, 1778, and headed downriver towards Kaskaskia and fame.

After four days of rowing down the Ohio, Clark’s men disembarked at the site of an abandoned French fort known as Fort Massac (near present-day Metropolis, IL). Clark was concerned that his unit would be seen by one of the many travelers on the river and the garrison at Kaskaskia informed of the army’s approach. Consequently, Clark led his men on a six-day trek through roughly 120-miles of the dense Illinois wilderness before arriving on the south bank of the Kaskaskia River just across from the town late in the evening. Fittingly, the date was July 4.

The band that emerged from the woods was a rough looking bunch, hungry, unshaven, and filthy with their clothes in tatters after walking for a week through brambles and branches. As the men stared at the fort and adjacent town, all was still with no signs of their presence being detected. Clark’s decision to go cross country from Fort Massac had been wise.

Getting across the river was the next challenge, but that was solved by scouring the riverbank and finding a few boats to ferry the men over. Around midnight, the Americans cautiously approached the fort, prepared to launch their assault. Much to their surprise, no sentry was on duty and the gate was wide open. Clark’s men quietly filtered into the compound and stationed themselves at all critical points, before breaking the night’s solitude with cries announcing the fort and town were taken.

The acting Lieutenant Governor, Phillip de Rocheblave, a former French army officer who had fought at the Battle of the Monongahela, was defiant but the rest of the residents and local militia not so much. They were all Frenchmen who had no great love for their British masters and had no objection to their American liberators. Incredibly, Clark’s audacious plan to capture this distant British outpost had been achieved without firing a shot.

Clark, showing wisdom beyond his years, immediately implemented very liberal and lenient policies towards the people of Kaskaskia and began a successful campaign to win their hearts and minds. He next dispatched Captain Joseph Bowman and a contingent of thirty men along with Father Pierre Gibault, Kaskaskia’s priest since 1770, to Cahokia, about fifty miles to the north, to convince that town to surrender as well. Cahokia’s leaders, recognizing the futility of resistance, complied on July 6, and the far west of this British province was secure, at least for now.

Next week, we will discuss Clark’s winter march to take Fort Sackville. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.