The American Revolution Moves West

Soon after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the fledgling United Colonies invaded the British Province of Quebec. Despite the heroic efforts of men like General Richard Montgomery, Colonel Benedict Arnold, and Colonel Daniel Morgan, the 1775-76 invasion failed at the granite walls of Quebec City. A second, lesser known invasion, led by George Rogers Clark succeeded wonderfully a few years later, resulting in the largest capture of British territory during the American Revolution.

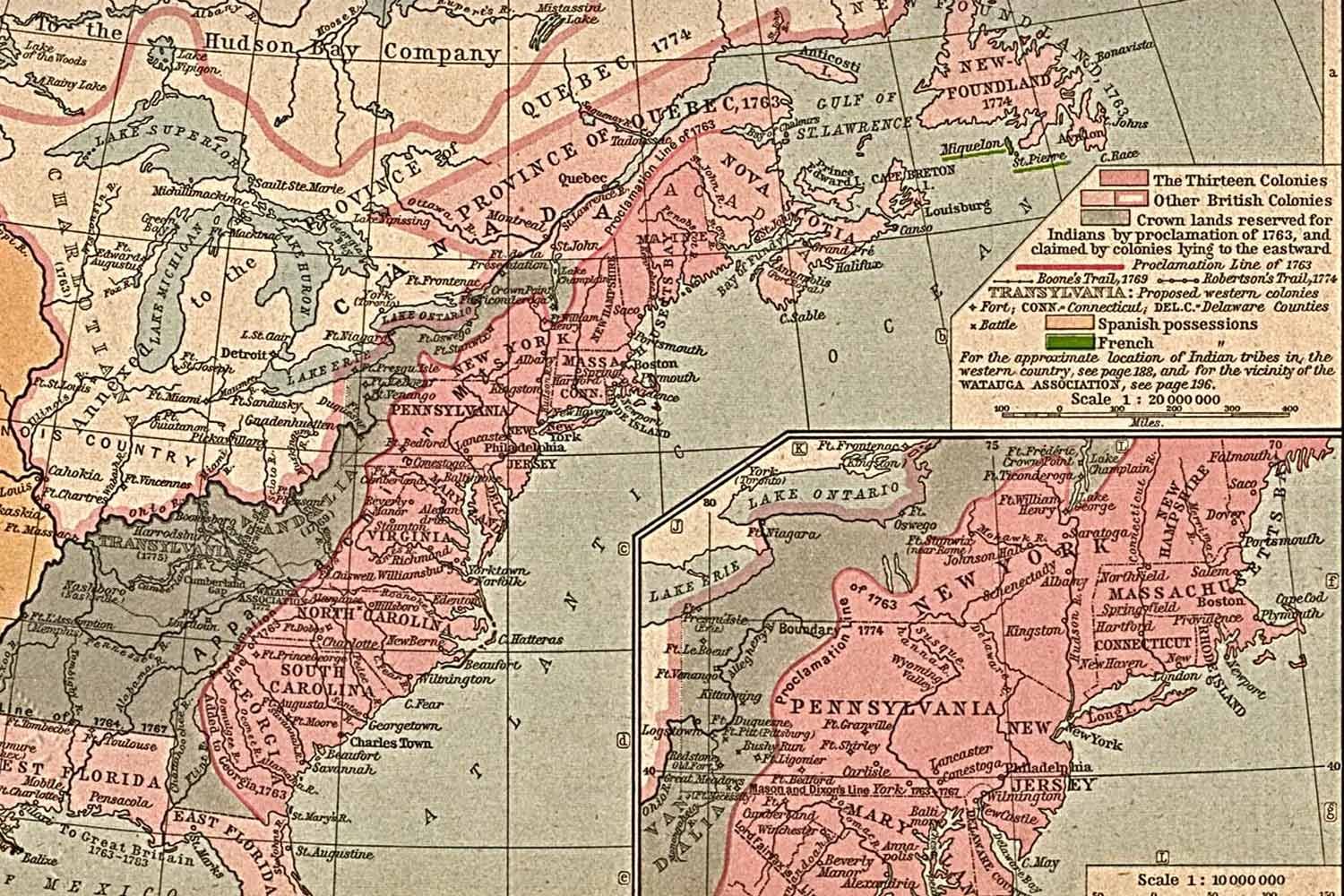

At the outbreak of the war, the largest colony in British North America was the Province of Quebec. Due to the annexation of vast lands from the Quebec Act of 1774 which tripled the size of this northern province, its domains extended from the Atlantic seaboard to beyond the western shores of Lake Superior and south from the Great Lakes along the length of the Ohio to its mouth at the Mississippi River. It was here that Clark, this remarkable Patriot, would leave his mark on American history.

In 1776, Clark was living in Kentucky, which at that time was very lightly settled and part of Fincastle County of the colony of Virginia. Clark called for a convention of the residents and convinced them to ask Virginia’s Assembly to declare Kentucky a separate county. The settlers elected Clark and John Gabriel Jones, a local attorney, to represent them in the Assembly and to take their request back to Williamsburg.

That his fellow Kentuckians would follow the lead of this twenty-three year old practically penniless surveyor who had only briefly resided in the area, speaks volumes of the natural leadership abilities of Clark. He was six feet tall possessing a muscular stocky build with sandy colored hair and piercing blue eyes. In the words of one contemporary, Clark had an “appearance well calculated to attract attention…rendered agreeable by his manly deportment and the intelligence of his conversation.”

Clark gave the petition for countyhood to his boyhood neighbor Thomas Jefferson who presented it to the Virginia Assembly, and, on December 31, 1776, the County of Kentucky was officially established with Harrodsburg as the county seat. It was hoped that this change would provide improved governance to Kentucky and greater security from Indian attacks.

During a very eventful 1777 in the east, Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga, the British occupied Philadelphia, and Washington’s men suffered at Valley Forge. As the year unfolded in the west, Shawnee and Delaware raids into Kentucky increased in frequency and ferocity. The first priority of the new county was to establish a local militia to defend against these attacks and, on March 5, 1777, Clark was commissioned as a Major in the Kentucky County militia. Because the two men elected over him, Colonel John Bowman and Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Bledsoe, declined to actively serve, Clark became the acting commander of the new unit.

“General Guy Carleton.” Wikimedia.

On the British side, a debate ensued regarding whether or not Indians should be supplied and encouraged to help crush the rebellion in the colonies. Those with a more humanitarian bent like Sir Guy Carleton, Governor General of Quebec, argued against the idea on both practical and moral grounds. However, that party was overruled by King George and his ministry who seemed to want victory by any means.

Consequently, in March 1777, orders were issued by Lord George Germaine, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to Carleton to “…direct Lieutenant Governor (Henry) Hamilton to assemble as many of the Indians of his district as he can” and commence what would prove to be a ruthless frontier war.

The news was well received by Hamilton who thought Carleton was too soft on the rebellious colonists. That could not be said of Hamilton who by the end of the war had acquired the nickname of “Hamilton the Hair Buyer” for his offer to purchase as many American scalps as the Indians could take. By September 1777, Hamilton boasted that “eleven hundred and fifty warriors are now dispersed over the frontiers” and Kentucky teetered on the brink of collapse. In December, only three settlements remained in Kentucky: Harrodsburg with sixty-five armed men, Boonesborough with twenty-two, and Logan’s Fort with fifteen.

But the ever energetic and motivated Clark was not a man to be put off by adversity. He had previously created a spy network to keep tabs on the British across the Ohio River in what was now the Province of Quebec, hoping to strike a blow at his adversaries when the time was right.

That opportunity came in June 1777 when two of Clark’s spies, Benjamin Linn and Samuel Moore, reported to Clark that the British fort at Kaskaskia near the Mississippi was undefended by British regulars, relying entirely on local untrained militia of French descent. Clark recognized the post was ripe for the taking if he acted quickly.

As to be expected, Clark’s primary goal as commander of the Kentucky County militia was to stop Shawnee raids into Kentucky from their villages across the Ohio. He soon conceived a plan to capture the British outposts in the Mississippi Valley and along the Wabash River that were on the flanks of these Indian towns to help achieve his objectives.

Next week, we will discuss Clark’s conquest of the Illinois Country. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.