The Early Life of George Rogers Clark

On the eve of the American Revolution, the lands west and south of the Appalachians were ripe for conquest. French settlers in the Ohio River Valley resented their new British masters; the fledgling United States had a ready-made ally in Spain who wanted to oust the British from Florida; and a growing contingent of Americans were in Kentucky with more of their countrymen on the way.

To further compound the matter, Parliament passed the Quebec Act in June 1774 which granted inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, all French Catholics, the right to freely practice their Catholic faith. Concerned with the growing unrest in the American colonies, the Act was passed to keep the 90,000 former Frenchmen living in Quebec in the British fold. While this legislation pleased the Quebecois, the largely Protestant American colonists viewed it as a vindictive affront by a hostile Parliament and a threat to their way of life.

Perhaps more importantly, the Act stretched the boundaries of the Province of Quebec to the Ohio River in the south and as far west as the Mississippi, tripling the land area of the province. In the eyes of Americans interested in western lands, the legislation essentially placed a stranglehold on their dreams of westward expansion and investment north of the Ohio.

All that was needed to exploit this cauldron of trouble and take over this vast land was an intrepid man with a vision and a band of determined followers. That leader would emerge in the person of George Rogers Clark, and his extraordinary efforts would secure the Ohio River Valley for the United States.

Clark was born on November 19, 1752, in Albemarle County, Virginia on the 410-acre family farm at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. His parents were John and Ann Rogers Clark who had moved there from the tidewater region of Virginia soon after they married in 1749. Just a short 2 ½ miles away was Shadwell plantation, Peter Jefferson’s estate, where his son Thomas was born in 1743. The destiny of the future President and the Clarks would be intricately interwoven in the decades to come.

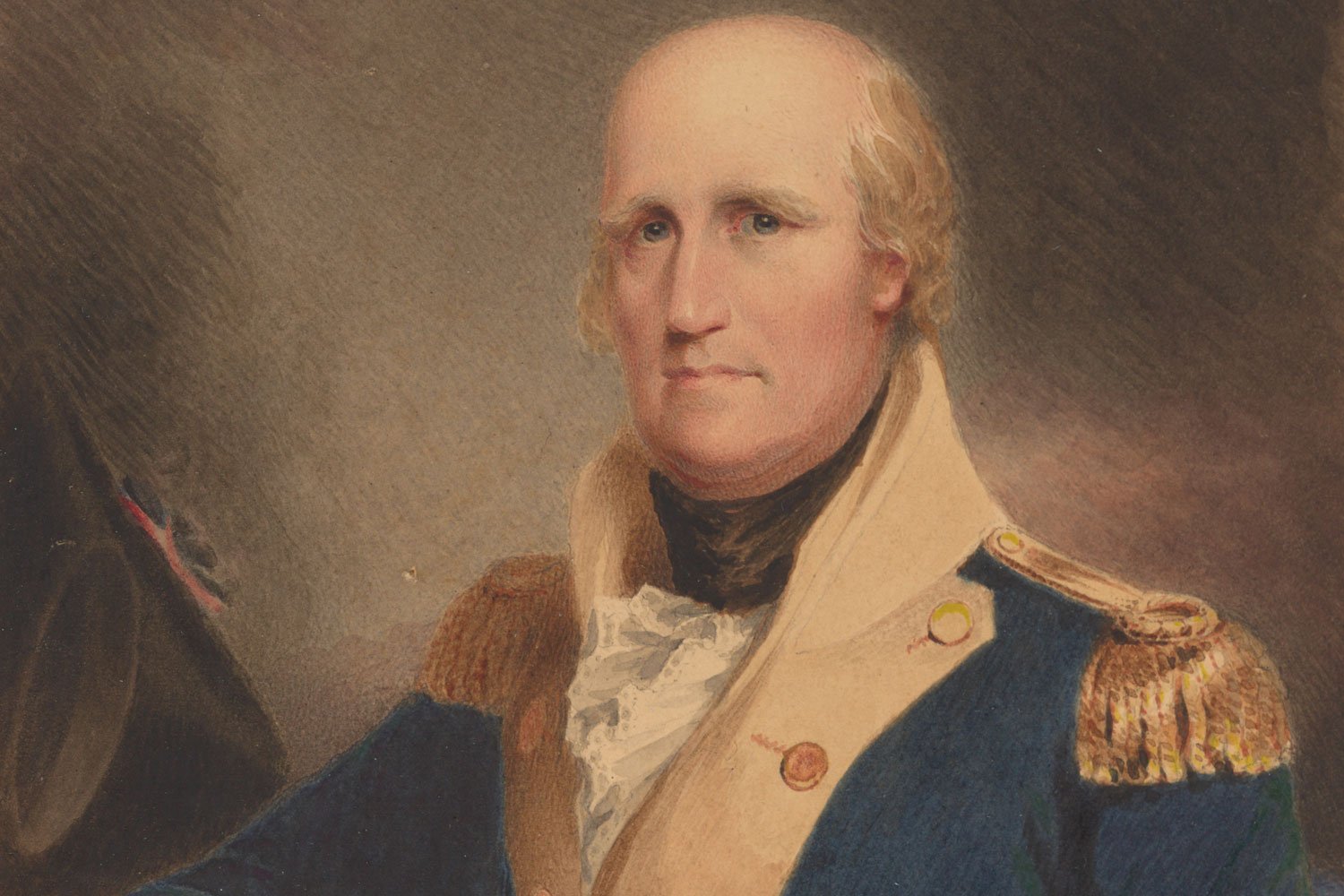

“William Clark.” Wikimedia.

Over the years, Ann, by all accounts a hardy, talented woman, bore John ten children, four girls and six boys. They were a strong, independent family and, when war broke out, five sons from this remarkable Patriotic clan served as officers in the American Revolution. The only son who did not serve was the youngest, William, who was not old enough to join up, much to his disappointment. However, William would become the most famous sibling of the bunch when he joined with Meriwether Lewis to lead the Corps of Discovery in exploring the Louisiana territory from 1803-1805, the greatest exploration in American history.

After the outbreak of the French and Indian War, the Clarks grew concerned about the increasing frequency of Indian raids along the Virginia frontier. In 1756, they moved to Caroline County when John’s uncle left the family a 170-acre farm along the Rappahannock River. It was here that George Rogers would spend the bulk of his childhood, including eight months of schooling, the only formal education George Rogers would ever receive.

His father was willing to pay for more classroom time, but the schoolmaster, Clark’s uncle Donald Robertson, despaired of ever getting the rambunctious George to settle down. Concluding that his young relation was “not very apt at learning,” Robertson recommended the parents invest their money elsewhere.

Recognizing George’s natural restlessness precluded farming as an occupation, father and son agreed George should try his hand at surveying. This profession required stamina and vigor, which George had in abundance, and promised exciting escapades in the great outdoors. George’s grandfather John Rogers taught him this craft, and George proved to be an excellent and eager pupil.

At age nineteen, with a head full of knowledge and seven pounds sterling worth of surveying equipment, a copy of Euclid’s Elements (the classic Greek treatise on mathematics essential to surveying), a bedroll, and a rifle, George Rogers headed west to make it on his own.

For much of the next two years, George mapped and surveyed the Kanawha River Valley in present day West Virginia. During that time, the area became a hotbed of Indian activity and raids, with numerous atrocities being committed on settlers along the frontier. In 1774, Virginia’s Royal Governor Lord Dunmore, led an expedition of Virginia militiamen which included Clark into Ohio Country to punish the Indians and make the area safe for British American colonists.

The effort, known as Lord Dunmore’s War, was brief in its duration and only one major battle was fought, the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10. This engagement was a resounding victory for the Virginians and the Delaware and Shawnee begged for peace. The adventure gave George Rogers his first taste of military life, as he was given a Captain’s commission and a company command in the Virginia militia. Although Clark saw no combat action, the thrill of the campaign and the manly, martial existence suited him to a T.

Next week, we will discuss the American Revolution’s move to the west. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.