England Reigns Supreme Following French and Indian War

The British American experience since 1607 when the first English settlers arrived in Jamestown had largely been confined to the eastern seaboard north of Spanish Florida. As the British began to expand beyond this Atlantic bubble in the mid-1700s, they came into conflict with their longtime nemesis, the French, primarily over which nation would dominate the lucrative fur trade in the Ohio Country.

In 1754, Colonel George Washington and a contingent of soldiers from Britain’s Virginia colony ambushed a French force at Jumonville Glen near present day Pittsburgh. This skirmish placed the two countries on a path that eventually led to the French and Indian War.

By 1760, due to a string of battlefield defeats, France lost all its northern possessions to England. In 1759, Niagara surrendered to Sir William Johnson and Ticonderoga yielded to Sir Jeffery Amherst, while General James Wolfe, in his final act, became immortalized as the conqueror of Quebec. Then on September 8, 1760, the final French bastion in Canada, Montreal, surrendered to the British without a shot being fired.

Two years later, despite the war drawing to a dismal close for the French, King Charles III of Spain, the cousin of France’s King Louis XV, joined the conflict on his cousin’s side. France, fearful of having to surrender their Mississippi Valley possessions to their arch enemy England, signed away French Louisiana to the Spanish in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762.

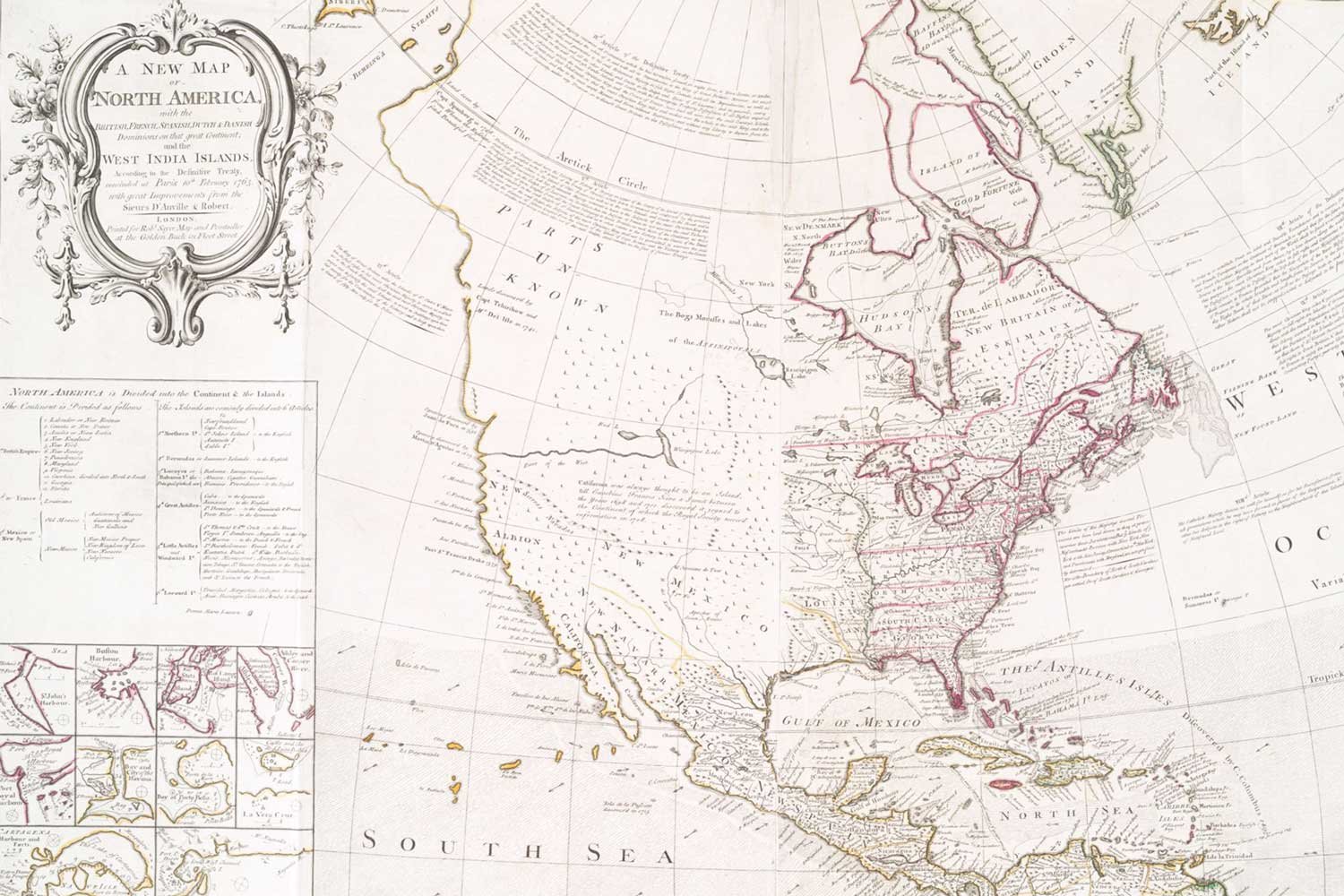

When the French and Indian War formally ended with the Treaty of Paris in February 1763 (not to be confused with the Treaty of Paris of 1783 which ended the American Revolution), the map of North America was redrawn. France was basically expelled from the continent, but it retained a strong influence in Canada, New Orleans, and in other outposts it had established in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and around the Great Lakes. Spain was forced to cede its valuable colony of Florida to the British but allowed to retain its possessions west of the Mississippi, as well as the vital river port of New Orleans.

To the victor goes the spoils and, accordingly, England was awarded all lands east of the Mississippi to the Atlantic seaboard and from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, except for New Orleans. To better manage their new possessions along the Gulf Coast, the British created two colonies, East Florida and West Florida, out of what had been Spanish Florida, with naval bases at Mobile and Pensacola. But by 1776, there were just 1,000 British subjects living along the Gulf Coast, with only 100 regular soldiers to man the forts.

The British also established garrisons in the Ohio River Valley and around the Great Lakes in areas originally settled by the French. The key outposts were Fort Sackville on the Wabash River (in present-day Vincennes, Indiana), Fort Detroit commanding much of the Great Lakes, and Kaskaskia and Cahokia near the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi in far-western Illinois. But due to a lack of manpower and virtually no settlement by British colonists, these frontier garrisons, like those along the Gulf, were lightly defended.

To better control traffic and trade on the Mississippi River, the British set up forts along the east bank of the lower Mississippi at the former French settlements of Natchez and Baton Rouge, issuing land grants to officers who had served with distinction in the French and Indian War. But by the start of the American Revolution, there were just 2,500 British colonists living along the vast Mississippi delta, almost all of them concentrated in Natchez and Baton Rouge.

“The Royal Proclamation of 1763.” Wikimedia.

The reason these almost limitless lands acquired in the Treaty of Paris remained unsettled in the land-hungry society of colonial America was partly because of the Royal Proclamation issued on October 7, 1763. This Act temporarily disallowed settlement west of the Eastern Continental Divide from Georgia to northern Pennsylvania and north of the St. Lawrence Divide all through New England.

Although it was never intended to be a permanent barrier to English expansion further west but rather designed to allow for an orderly progression into the Trans-Appalachian region, the Act was very unpopular. Neither British colonists nor land speculation outfits like George Washington’s Ohio Company were as patient as King George and they wanted to move at a faster pace.

Moreover, some of the land declared off-limits to settlement had already been settled. Regardless, no arbitrary line drawn by ministers in London 3,000 miles away and not policed locally was going to deter determined colonists from crossing the Appalachians.

This trickle of new settlers, along with other policies implemented by the British commander General Jeffery Amherst, served to irritate Indians living in the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley. Used to the non-invasive and hands-off practices of the French, Native tribesmen resented their new masters' more formalized system of governance which treated them like conquered peoples. This resentment would erupt in May 1763 with disastrous results for British garrisons and settlers.

Next week, we will discuss Native preparations to strike back. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.