The Conspiracy of Pontiac

In the spring of 1763, following the conclusion of the French and Indian War, the Ohio Country and the Great Lakes region officially changed from French to British control. While markedly affecting the two European nations, the most significant impact fell on the Native Americans who lived in the region. Generally, these nations were unhappy with this transfer of power and worried that their way of life would be adversely affected. A charismatic Indian chieftain named Pontiac was determined to prevent this from happening.

Pontiac was a powerful chief of the Ottawa tribe, one of predominant Native groups around Lake Huron and the territory north of Lake Erie. Little is known of Pontiac’s early life, but it is believed he was born around 1715 in a village in present-day northern Ohio or southern Michigan. Contemporary accounts credit Pontiac with being a gifted warrior; a man of courage, resolution, and wisdom. At the time of the rebellion that bears his name, he was about fifty years old, a leader of great renown, and living along the north bank of the Detroit River near Fort Detroit.

Like other Indians in the area, Pontiac had a great hatred for the British, built largely upon seven years of fighting them while allies of the French. Moreover, the Natives sensed the British held them in low regard and were indifferent to their needs. This feeling was soon confirmed when General Jeffery Amherst, the military commander of the region, began to withhold presents from the tribes.

As trivial as this may seem to us today, to the proud Natives this reduction in gifts was viewed as an insult and an affront that demanded retribution. This change in treatment was partly due to the different way the French and the English viewed the Natives. While the French had lived amongst and befriended the Indians for almost a century, the British, everyone from fur traders to soldiers, considered them a conquered people and treated the Natives with contempt. Moreover, to ingratiate themselves to the Natives and to win their confidence, the French had always been extremely generous with their gifts. So much so, that the Indians came to rely on European weapons, clothing, and even household items, and could not get by without them.

Conversely, the British saw little reason to continue this policy and, almost immediately, reduced or eliminated presents to the Indians. While the paltry number of gifts was certainly insulting, more importantly, the Indian dependency on the iron pots and farming tools that the British no longer supplied led to hunger and hardship within the tribes.

But the most unforgivable sin of the British, the one thing that most irritated the Natives, was the encroachment on their ancestral lands by British American colonists, and the permanent settlements they established. Pontiac and other Indian leaders recognized that their very way of life was being threatened by this influx of settlers and they naturally pushed back.

It didn’t help that the French were continuing to incite the Natives with tales of British atrocities and plans to exterminate all the tribes. French fur trappers and traders made their way into native villages throughout the region to spread the word that the British intended them great harm. To give the Natives hope and bolster their spirits, these Frenchmen falsely asserted that an army from France was already on its way to oust the British and reclaim their lost lands.

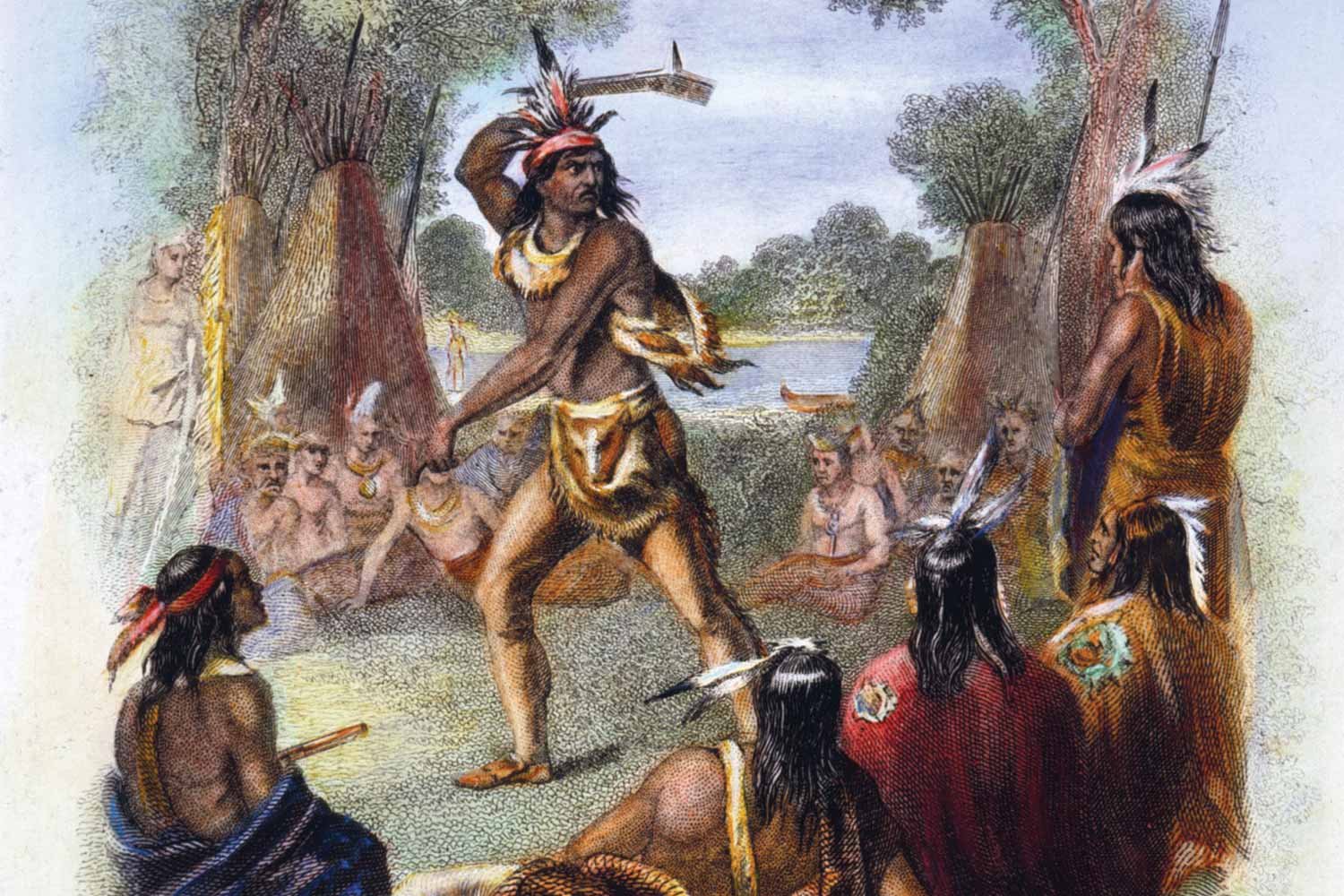

“Chief Pontiac.” Wikimedia.

Accordingly, in late 1762, Pontiac sent emissaries to the numerous tribes around the Great Lakes and Ohio Country, and as far west as the lower Mississippi. These ambassadors delivered vehement speeches in hogans and wigwams across the region detailing the treachery of the British and proclaiming that the French were coming to their aid. The orations always concluded with the speaker flourishing a red or black wampum war belt and throwing down a red stained tomahawk, the Native American sign of war, and challenging the Indians to join the endeavor to expel the British.

By the fall of 1762, this effort had gained countless converts to the cause and included Seneca, Potawatomi, Ottawa, Ojibwa, Wyandot, and many others. Pontiac’s call served to galvanize the Native Americans into a loose knit confederation, no easy task given the independent nature of tribal culture.

The blow was to be struck sometime in May, with the initial assault reserved for Pontiac. There were nine British forts in the Ohio Country and around the Great Lakes and the general idea was that each tribe would attack the fort in its immediate vicinity and all at roughly the same time. This well-coordinated assault would prevent the many forts from informing and supporting one another. Once that task was completed, the tribes were to turn against any settlers living along the frontier and kill as many as possible, sparing no one. The hope was that the terror inspired by these unmerciful attacks would discourage future settlement.

With the approach of spring in 1763, Native warriors began to leave their winter hunting grounds and gather near the British forts as they did each year. Following one last grand council meeting at the Ecorces River, Pontiac was ready to put his master plan in motion.

Next week, we will discuss Pontiac’s Rebellion. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.