The Siege of Fort Stanwix

The American Revolution battle with the greatest loss of American lives was not one of the better-known engagements such as Bunker Hill, Brooklyn Heights, or Camden. It was a somewhat forgotten fight in western New York at a place called Oriskany. Although not well-remembered, it had a significant impact on our fight for independence.

In the summer of 1777, General John Burgoyne had initiated a three-pronged advance towards Albany, New York with the goal of securing the water highway from Montreal across Lake Champlain and down the Hudson River to New York City. If successful, this operation would effectively split New England off from the rest of the American colonies, allowing the British to defeat the American rebels one section at a time.

Besides Burgoyne’s force coming south from Montreal and Sir William Howe’s army moving north from New York City, a third unit was expected to move east from Lake Ontario along the Mohawk River Valley. Although considered by some as simply a diversion, it was still a force to be reckoned with and thus would draw American soldiers away from the main Continental army coalescing around Albany.

The leader of the British contingent coming from the west was forty-four-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Barrimore “Barry” St. Leger, an Irish born British army veteran of twenty years, with much of that time spent in North America. He was leading about 1,800 men: 900 British Regulars, German mercenaries, and Loyalists and 900 Indians, mostly Senecas and Mohawks.

The primary target for St. Leger’s army was Fort Stanwix, started in 1758 at the height of the French and Indian War and named for British General John Stanwix. The fort had not been used since the late 1760s and had fallen into disrepair. Not surprisingly, when the Americans marched in and took over the fort in August 1776, they renamed it Fort Schuyler after General Phillip Schuyler, the American Northern Theater commander. For this story, we will use the original name, Fort Stanwix.

The fort was located at the Oneida Carry or Great Carrying Place, one of the most strategically critical sites in colonial North America. Used by Indians for centuries, the Oneida Carry was a portage of roughly six miles between the Mohawk River (near today’s Rome, NY) and Wood Creek which flowed into Oneida Lake and continuing into Lake Ontario. Thus, whoever controlled this hinge point controlled the only water highway in colonial America that connected New York City and the Eastern seaboard with the Great Lakes and America’s vast interior.

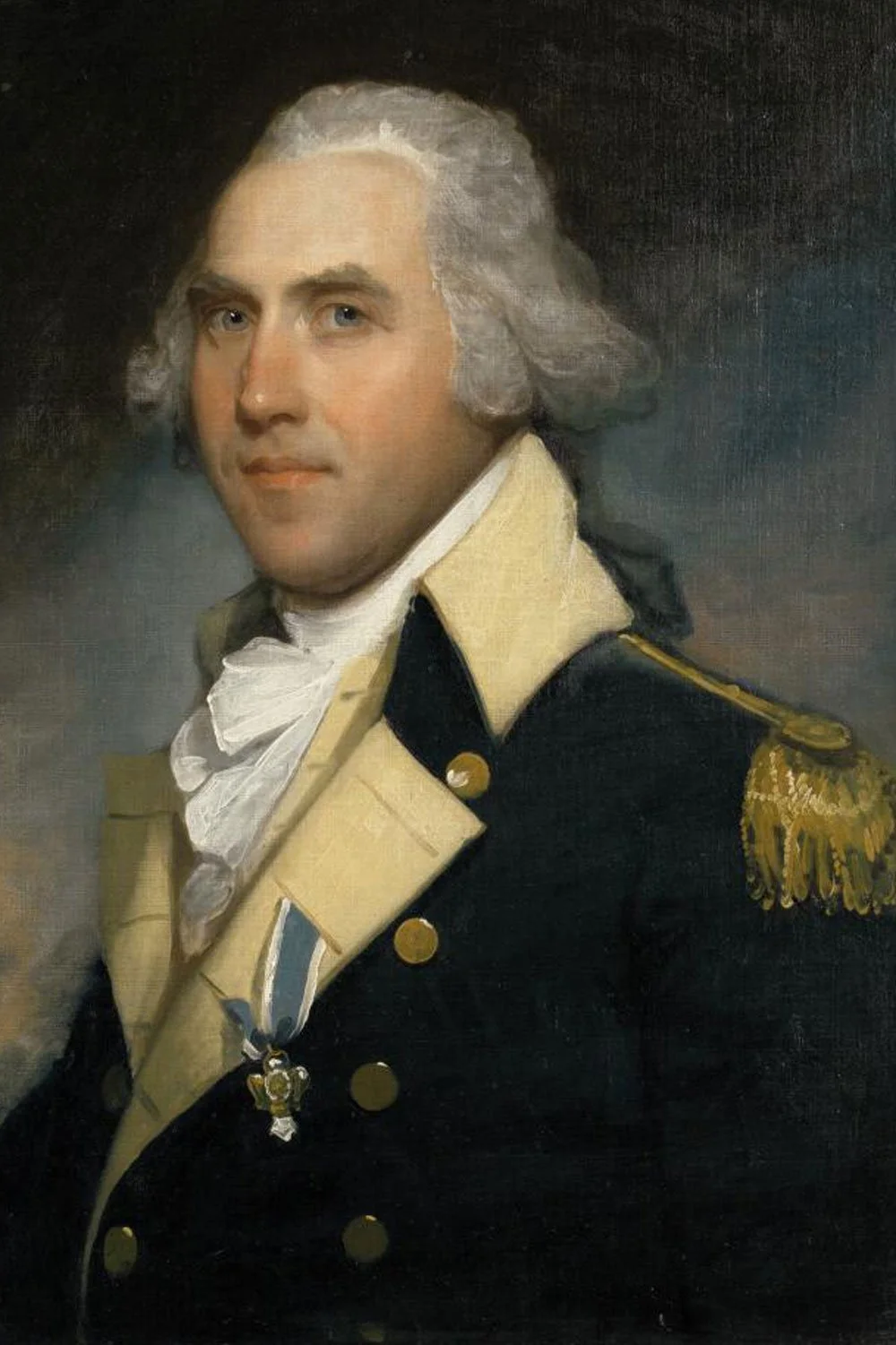

Gilbert Stuart. “Portrait of General Peter Gansevoort.” Munson Williams Proctor Art Institute

The commander of the American garrison at Fort Stanwix was Colonel Peter Gansevoort who led the 550-man Third New York Regiment. Gansevoort was a member of one of the first and most prominent Dutch families in the area, dating their time in Albany to 1660 when it was the Dutch colony of Fort Orange. Although only twenty-eight years old, Gansevoort had distinguished himself during the 1775-76 invasion of Quebec and possessed youthful energy and a mature confidence.

St. Leger’s force arrived at Fort Stanwix on August 2, 1777 and were disappointed to find the fort in relatively good order, contrary to official reports from local Loyalists. The improved defenses were largely the result of the efforts and superb leadership of Gansevoort and Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willett, his very capable second-in-command. Rather than risk a costly assault, St. Leger settled in for a siege.

Just days before St. Leger’s appearance, a call for help had been sent to General Schuyler in Albany imploring the general to hasten a relief force to Fort Stanwix. On the way to see Schuyler, the messenger stopped off to inform General Nicholas Herkimer, the commander of the Tryon County militia, of what was transpiring at the fort.

Herkimer’s base was Fort Dayton (present day Herkimer, NY) a little over thirty miles away. Although every able-bodied man under the age of sixty in the county was required to muster when the militia was summoned, almost all the men were farmers and harvest time was getting close. Consequently, the assembly took a few days but by August 4, 700 militiamen had gathered, and the relief march began.

The evening of August 5 Herkimer’s men made camp at a small Oneida village named Oriska. The enemy was about seven miles away and, as far as Herkimer could tell, was unaware of his presence. The plan was for Herkimer to approach unobserved and fall on the rear of the besieging force while at the same time the American garrison inside the fort would sortie out; thus, creating a sort of hammer and anvil effect on the Brits. It was a sound plan, but like so many sound plans, it would go astray.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Oriskany. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.