Americans Victorious at Saratoga

Following the setback at Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777, in which the British had lost another 900 men, and despite the deplorable condition of the British Army, General John Burgoyne still had hope that he could somehow extricate his forces from the grip of the Continental Army. But the noose was tightening, and Burgoyne and his other commanders knew they had to act fast.

Even at this late date, Burgoyne still had over 6,000 well-trained professional soldiers under his command. While the Continental Army numbered about 12,000 men, they were all sitting in front of Burgoyne, protecting the road south to Albany. The road back from whence the Redcoats came, all the way back to Fort Ticonderoga, was practically undefended.

The British were only 15 miles from Fort Edward, defended by 100 Americans, and about fifty miles from Fort Ticonderoga which the British still held. If Burgoyne were willing to jettison his cannons and much of the baggage train, the British Army could be saved by four days of forced marches back to Ticonderoga. That, of course, would be admitting defeat and that was something Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne’s ego would not allow.

The moment proved too much for General Burgoyne, as he seemed to freeze and had his troops dig in where they were. With each passing day, more American militiamen arrived tightening the noose around the Brits, but despite daily admonitions from his other generals to begin the retreat, Burgoyne did nothing.

Finally, on the night of October 12, General John Stark, the hero of Bennington, and one thousand New Hampshire militiamen crossed the Hudson and sealed off the one road left open to Fort Edward and safety. The deed was done, and Burgoyne had no choice but to surrender.

On October 17, General John Burgoyne donned a brand new scarlet red uniform with glittering gold braid and a new hat with plumes, the regimental outfit he had packed along to wear in his triumphant entry into Albany, and led his men toward the American camp. One can only imagine the supreme humiliation that Burgoyne and his brave lads must have felt.

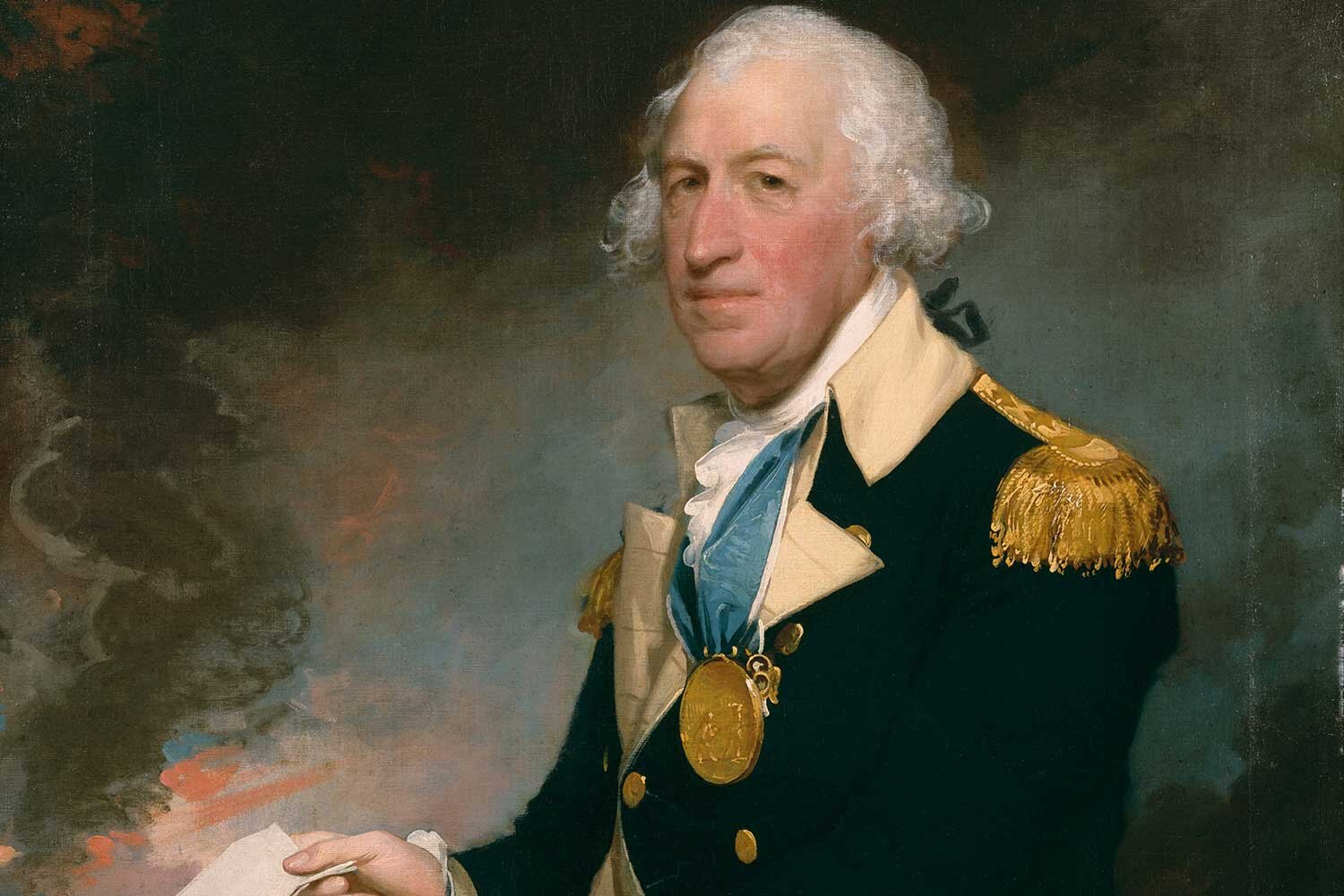

All told, Burgoyne surrendered some 6,000 men, roughly half Brits and half Germans, along with numerous artillery pieces and other weaponry, to General Horatio Gates. Interestingly, Burgoyne and Gates had known each other since 1745 when they served together as newly minted lieutenants in the British Army.

Gilbert Stuart. “Horatio Gates.” Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During the surrender ceremony, the Americans displayed the greatest professionalism to their adversaries, without any catcalls coming from the ranks. Lord Francis Napier noted, “They behaved with the greatest decency and propriety, not even a smile appearing in any of their countenances, which circumstance I really believe would not have happened had the case been reversed.”

The army was marched to Boston, about two hundred miles away. There, they were to have been paroled under a promise not to take up arms again in America during the Revolution. Unfortunately, politicians in Congress dishonored the terms to which both sets of generals had agreed and the British rank and file paid the price. These men, known as the Convention Army, were held as prisoners in deplorable conditions for six years. They finally went home in 1783.

Burgoyne, being an officer, went home to England in 1778 and spent much of the next two years trying to salvage his reputation. An inquiry in Parliament exonerated him for his defeat at Saratoga, but he was never again entrusted with a command.

Benedict Arnold’s shattered left leg never did heal all that well and ended up two inches shorter than his right. Worse than the physical damage, Arnold never seemed to recover from being denied the honors he felt he deserved for his exploits at Saratoga, as well as the other occasions when he had felt snubbed by Congress. Arnold’s deep disappointment would grow into unfathomable treason within two years.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should the Saratoga campaign matter to us today? The Continental Army’s resounding victory at Saratoga brought France into the war, an event that proved critical to our nation’s success. Given America’s lack of manufacturing, it is difficult to imagine the Continental Army could have sustained its needs for cannons, muskets, and gun powder throughout the war.

Additionally, the threat to England’s homeland and valuable sugar colonies in the Caribbean created by the French declaration of war changed the focus of the English Ministry and forced it to divide its military might. This division of resources eventually led to England to conclude it could not conquer the American colonies and led to the Treaty of Paris.

SUGGESTED READING

Saratoga, Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War, written by Richard Ketchum, is an excellent book of the Saratoga campaign. Ketchum details the events leading up to the Battles of Saratoga, the battles themselves, and the consequences of what happened there.

PLACES TO VISIT

Saratoga National Historical Park in Saratoga, New York is the site of arguably the most consequential battle of the American Revolution. Located about forty miles north of Albany, the historic park has a great Visitor’s Center with an orientation video and offers an excellent self-guided tour around the four square mile battlefield.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.