British and Americans Clash at Saratoga

By mid-September 1777, British General John Burgoyne, after crossing to the west bank of the Hudson River, was committed to continuing his advance towards Albany. There was only one road he could take to get there, and that road was strongly defended by an American army, twice as large as his own.

General Benedict Arnold, the Continental Army’s brilliant field commander, assisted by Colonel Thaddeus Kosciusko, a Polish military engineer, had emplaced the American troops in a virtually unassailable position on some high ground called Bemis Heights. To make matters worse for Burgoyne, he was operating blind because his Indian allies who acted as his scouts had all left after the disastrous defeat at Bennington. They had been promised easy bounty and plentiful scalps and that was just not happening.

At dawn on September 19, Burgoyne, unaware of the exact American position or its troop strength, was about three miles from Bemis Heights. Thinking Gates would be content to sit behind his barricades and wait for the British to attack, Burgoyne planned to move through heavy woods around the American left flank and take them in the rear. Burgoyne was correct about Gates, who hardly left his tent during the battle, but he had not reckoned on Benedict Arnold.

Arnold, anticipating Burgoyne’s move, pulled Captain Daniel Morgan’s Virginia riflemen and Major Henry Dearborn’s light infantry out of the trenches and sent them to fall upon Burgoyne’s forces before they could deploy. The Americans arrived at a place known as Freeman’s Farm just as the Brits were preparing to commence their attack around 1 p.m.

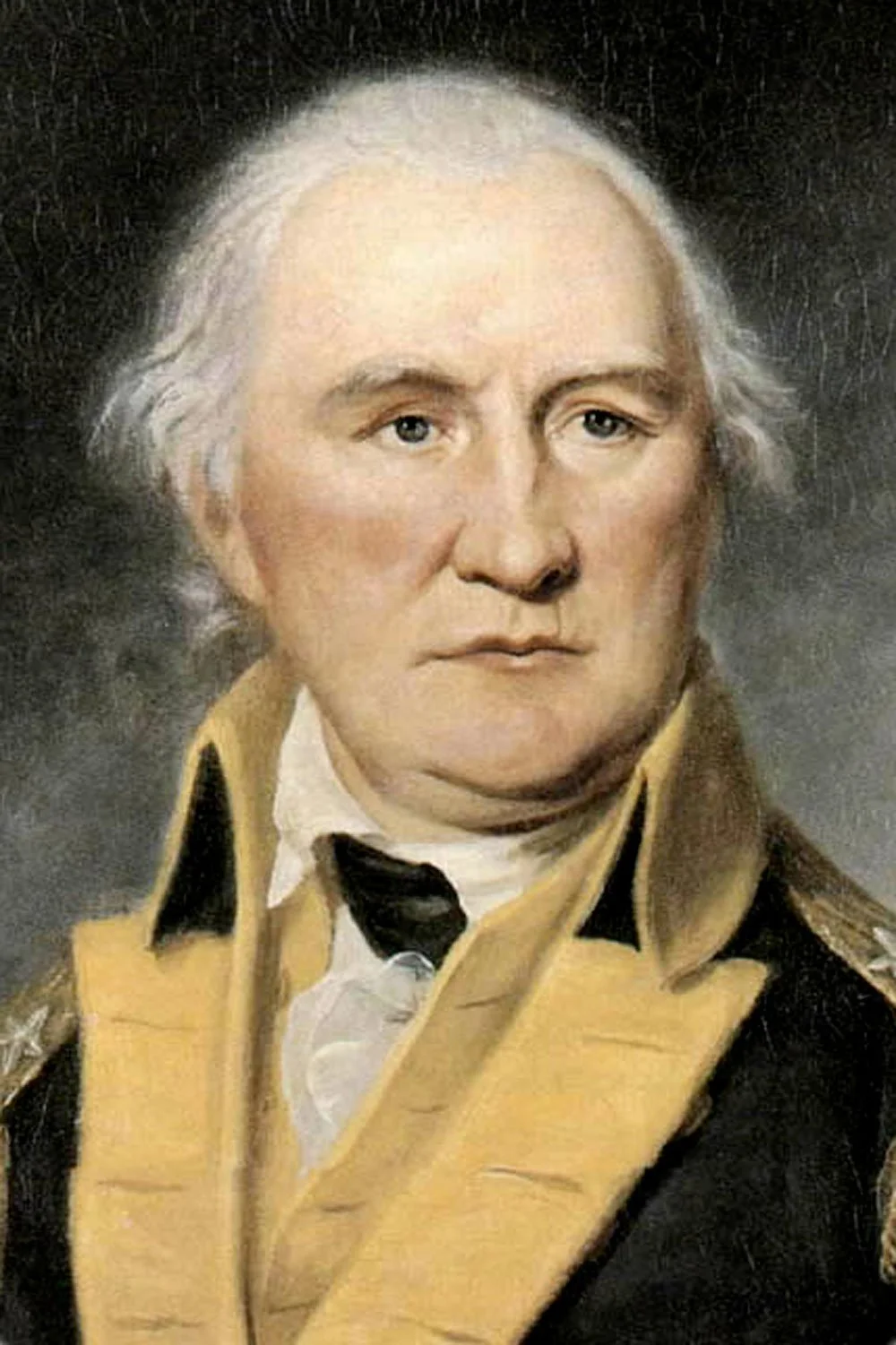

Charles Wilson Peale. “Daniel Morgan.” Wikimedia.

The Redcoats were astonished to find the Americans in front of them and a bloody melee ensued. Morgan’s sharpshooters soon began targeting all the British officers, knowing without their leadership the rank and file would become disorganized. Back and forth the two sides slugged it out in the rugged wooded hills, with attacks and counterattacks raging throughout the day.

Both sides were finding out that the ragged looking Americans, when properly led, were an equal match for the Brits. As Massachusetts Colonel John Glover stated, Burgoyne’s men were “bold, intrepid, and fought like heroes while our men were equally bold and courageous and fought like men, fighting for their all.”

Late in the day, as darkness was starting to fall, British reinforcements arrived and drove back the Americans. The field was theirs and, technically, so was the victory, but the Battle of Freeman’s Farm came at a cost Burgoyne could not afford to pay. He had lost almost 600 men, a tenth of his total force, losses he could not replace. By comparison, Americans had suffered 300 casualties, but they had more men arriving in camp every day.

The Americans had performed well, in large part thanks to General Arnold’s foresight and battlefield heroics. However, when General Gates, who was jealous of Arnold, submitted his official report of the battle to Congress, he failed to even mention Arnold’s efforts. This snub would have infuriated anyone, but for the hypersensitive Arnold it was too much.

A few days later when Arnold found out, he confronted Gates in his tent and two Major Generals had a profane shouting match while shocked subordinates and other soldiers watched and listened. The end result was that Gates ordered Arnold to his tent under a sort of house arrest, despite Arnold being the best commander in the Northern Army and the Brits just across the trenches and getting ready for another assault.

With his army starving and quick action seemingly required to save the day, Burgoyne hit the pause button on September 21. Early that morning, he had received a letter from General Henry Clinton, who was in New York with a small garrison, that Clinton might move north with 2,000 men to assist Burgoyne. There was nothing definite in this message, just a possibility. But that was enough for Burgoyne to decide to dig in where he was and hope for help. It was the worst of decisions.

For two and a half weeks, Burgoyne sat and waited for help that never came, and with each passing day his men grew more weary and hungrier. Finally, on October 7, unable to delay any longer, Burgoyne sent about 1,700 men in a reconnaissance in force, to determine the extent of the American position. They found it by mid-afternoon, but Burgoyne soon realized it was more than he had bargained for.

The Americans hit them hard, and the battle seesawed back and forth for several hours. Arnold, disregarding his house arrest and Gates’ orders, mounted a horse and raced to the sounds of the guns against Gates’ orders. Arriving at a critical juncture, Arnold led three Connecticut militia regiments in a valiant assault that captured a well-defended redoubt that anchored the British line.

With darkness falling, Arnold was severely wounded in the knee, the same one that had injured at Quebec, and was removed from the field. Arnold’s assault had broken the British line and carried the day for the Americans. But with Arnold gone and the shadows enveloping the field, the American attack ground to a halt.

Next week, we will discuss the British Army surrendering at Saratoga. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.