British and Americans Poised for Battle

In the eight short weeks since capturing Fort Ticonderoga without a fight, British General John Burgoyne had seen his army go from being invincible to facing starvation and defeat. More bad news arrived on August 28, when Native Americans brought word that a relief force under Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger coming from the west down the Mohawk River Valley had turned back.

With General William Howe sailing his army to Philadelphia and now with St. Leger in retreat, Burgoyne was on his own. The three-pronged British advance into New York to split New England from the rest of the colonies was down to just Burgoyne’s dwindling army, and they were mired down at Fort Edward on the east bank of the Hudson about 50 miles north of Albany.

Burgoyne knew his situation was becoming desperate and he must quickly choose between continuing his advance to Albany or retreat to Fort Ticonderoga and prepare winter quarters. Burgoyne, perhaps unable to endure the embarrassment of turning back, chose to move forward. On September 10, the British army began crossing the river to the west bank of the Hudson where the American Army was waiting for them.

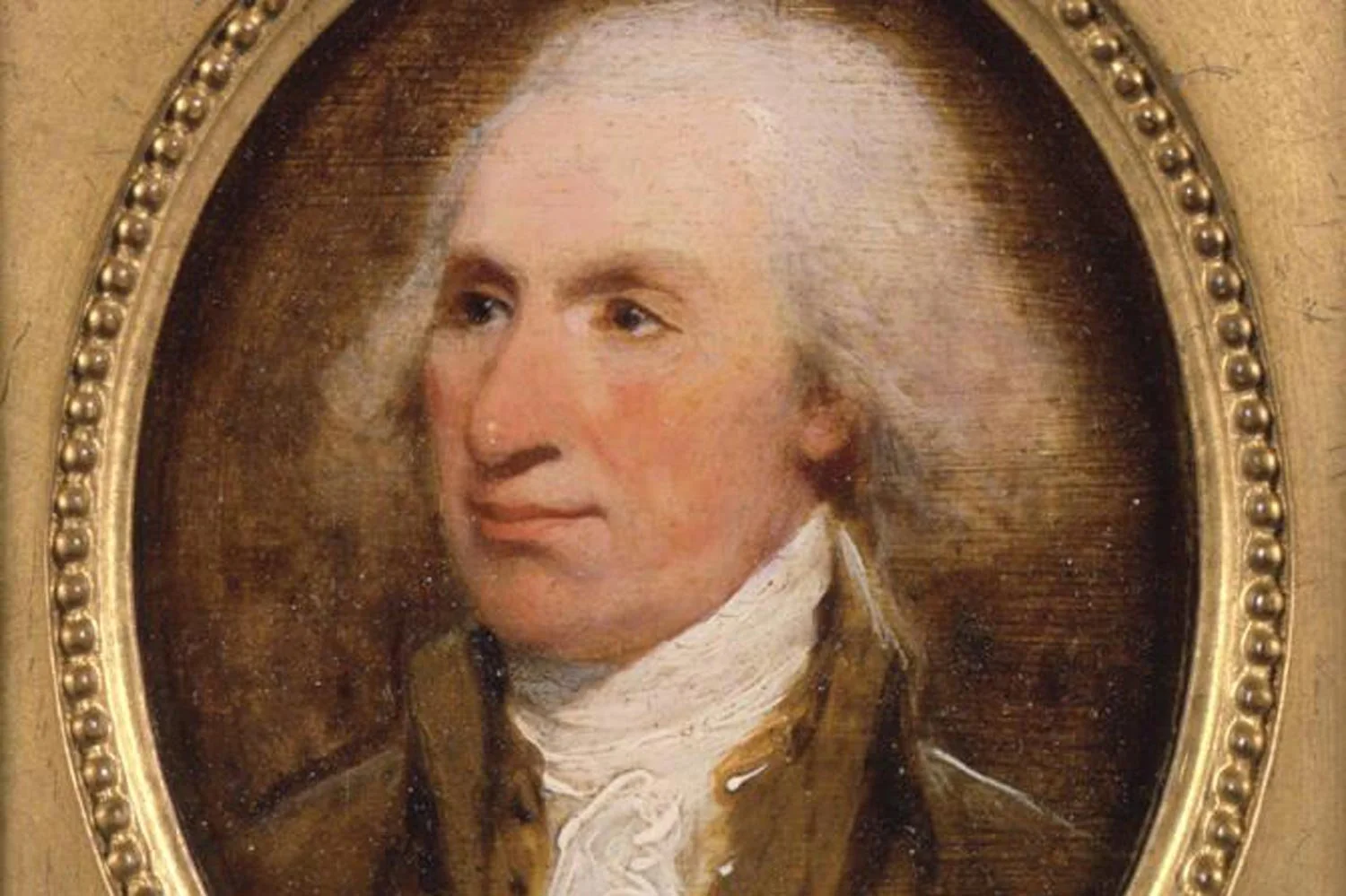

The Americans had been having some issues of their own. The commander of the Northern Department since June 1775 was General Philip Schuyler, a wealthy, devoted Patriot from upper New York state. Schuyler, who suffered no fools, especially politicians, could appear distant and a bit arrogant to those who acted or spoke foolishly.

John Trumbull. “Major General Philip John Schuyler.” New York Historical Society Museum & Library.

He was vehemently disliked by New Englanders in Congress who resented having the haughty General directing their regiments and failing to jump at their every demand. Although Schuyler’s retreat had been well executed and drained Burgoyne’s army of manpower and supplies, the poignant loss of Fort Ticonderoga was a perfect excuse to remove him from command.

Anxious to have someone more to their liking in charge, in mid-August, Congress replaced Schuyler with General Horatio Gates who had been Schuyler’s subordinate. Gates, a true scoundrel and covetous of Schuyler’s job, had been badmouthing his boss for over a year. Later, Gates would also try to discredit General Washington behind his back, hoping to get the commander-in-chief’s job. Fortunately for America, that time Gates’s scheming would not work out.

In any event, the retreat had also caused concern with General Washington, who was busy keeping an eye on General William Howe’s army based in New York. To remedy the situation in the north, Washington dispatched the best field commander in the Continental Army, General Benedict Arnold, to assist Gates and the Northern army.

Thomas Hart. “Colonel Benedict Arnold.” Brown University Library.

Since receiving his commission in March 1775, Arnold had risen to the rank of Major General and was already a bit of a legend for his battlefield exploits. Regarded by the English as the colonies’ most competent officer and by Americans as second only to Washington in terms of ability, Arnold was an aggressive, brave officer who was adored by his men.

Unfortunately, Arnold’s fame made him a target for his new boss, General Gates, who seemed to resent any success that was not his. That resentment shaped how Gates would use his talented subordinate and almost cost the Continental Army this campaign.

The biggest positive for the Americans was the way militiamen were responding to the call to arms. While Burgoyne’s army was shrinking almost daily, the American ranks were constantly expanding as new men arrived. They were motivated to protect their homes from the invading Brits, and an ugly incident that had fired up the men in the area.

Jane (Jenny) McCrea was an uncommonly attractive woman who lived near Fort Edward. On July 27, she was captured by Native Americans supporting Burgoyne’s Redcoats while they were raiding the region. They subsequently shot and scalped McCrea and proceeded to mutilate her body.

Despite the atrocities committed by Burgoyne-allied Native Americans happening at a frightening rate, this one seemed to really hit a nerve. Within weeks it was the talk of New England and New York state, with the story in every paper and the details getting embellished with every telling. In an age when men were expected to protect their womenfolk, angry militiamen came running to prevent further mayhem. By the time Burgoyne and his 6,000-man force confronted the American army, Gates’ army had grown to over 12,000 men.

Headquarters for the Continentals was in Stillwater, about fifteen miles south of Saratoga. General Benedict Arnold, knowing the Americans needed to find a more defensible position, persuaded Gates to allow Arnold to take the men forward and fortify an area known as Bemis Heights. This high ground was adjacent to the Hudson River and dominated the only road to Albany. Arnold knew Burgoyne would have to pay a heavy price to continue his march south.

Next week, we will discuss the fights at Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.