Burgoyne Battles American Wilderness and Continental Army

Despite his early successes of capturing Fort Ticonderoga and defeating the American rear guard at both Hubbardton and Fort Anne, Burgoyne now faced the greatest adversary of an army invading a foreign land: a lengthening supply line. As Napoleon remarked, an army marches on its stomach and the British soldiers were no exception.

The battlefield victories won by the Brits were dearly bought with casualties Burgoyne could not replace. There were also posts along the supply line to man which further reduced the number of troops Burgoyne could bring to bear in a pitched battle.

The roads were practically non-existent in the highlands of New York and those that were there were deplorable, certainly not constructed for the needs of a large army with an extensive baggage train. To add insult to injury, the Americans felled century old trees as they retreated down those forest paths and at all major stream crossings, forcing the Brits to expend time and energy clearing the way.

Moreover, the British discovered, much to their surprise, that the Americans could fight. As English Lieutenant James Hadden stated, the Redcoats discovered that “neither they (the British) were invincible nor the Rebels all poltroons. On the contrary… the enemy behaved well.” There was also more militia arriving every day.

The plan that had seemed so easy when Burgoyne was sitting in the parlors of London was anything but that now. With the army deep in the primeval forests of North America and a supply line that stretched to the wharves of English ports over three thousand miles away, Burgoyne was faced with a new reality. He stated that for every hour planning “how he shall fight his army, he must allot twenty to contrive how to feed it.”

Burgoyne’s beautiful army clad in their brilliant scarlet uniforms with shiny brass buttons were being starved and worn down by a group of New England farmers in their homespun clothing looking as if they were ready to go work their fields.

Living off the land was not an option either as General Phillip Schuyler, the Northern Department commander, instructed the American army to destroy any provisions they could not carry off as they retreated. This scorched earth policy along with the flight of the local residents left very little food for the Brits to scrounge.

By late July, the British army had reached Fort Edward, the post at the head of navigation for the Hudson River. It had taken three grueling weeks to travel the fifty miles from Fort Ticonderoga. With the army exhausted and practically out of food, Burgoyne paused his advance to let his supplies catch up. This pause would prove to be fateful, perhaps Burgoyne’s worst mistake during the invasion.

Meanwhile, in New York, while Burgoyne was slogging through the northern wildness, General William Howe, the overall commander of British troops in North America, loaded his 14,000 Redcoats onto troop transports. However, this formidable army did not head north up the Hudson to catch the Americans between the two British armies, but rather set sail for Philadelphia in the hopes of capturing the colonial capital.

This meant, of course, that Howe would not be supporting Burgoyne’s advance as Burgoyne and other English officials expected. Howe’s ego would not allow him to play second fiddle to Burgoyne despite Howe’s assistance being a crucial element of the master plan.

Burgoyne was informed of Howe’s decision on August 3 while Burgoyne’s army was in a holding pattern at Fort Edward, and he realized at once that his situation was becoming desperate. Soon thereafter, Burgoyne was informed by a local Loyalist that a large stockpile of food and horses was being held in Bennington, about 40 miles southeast of Fort Edward.

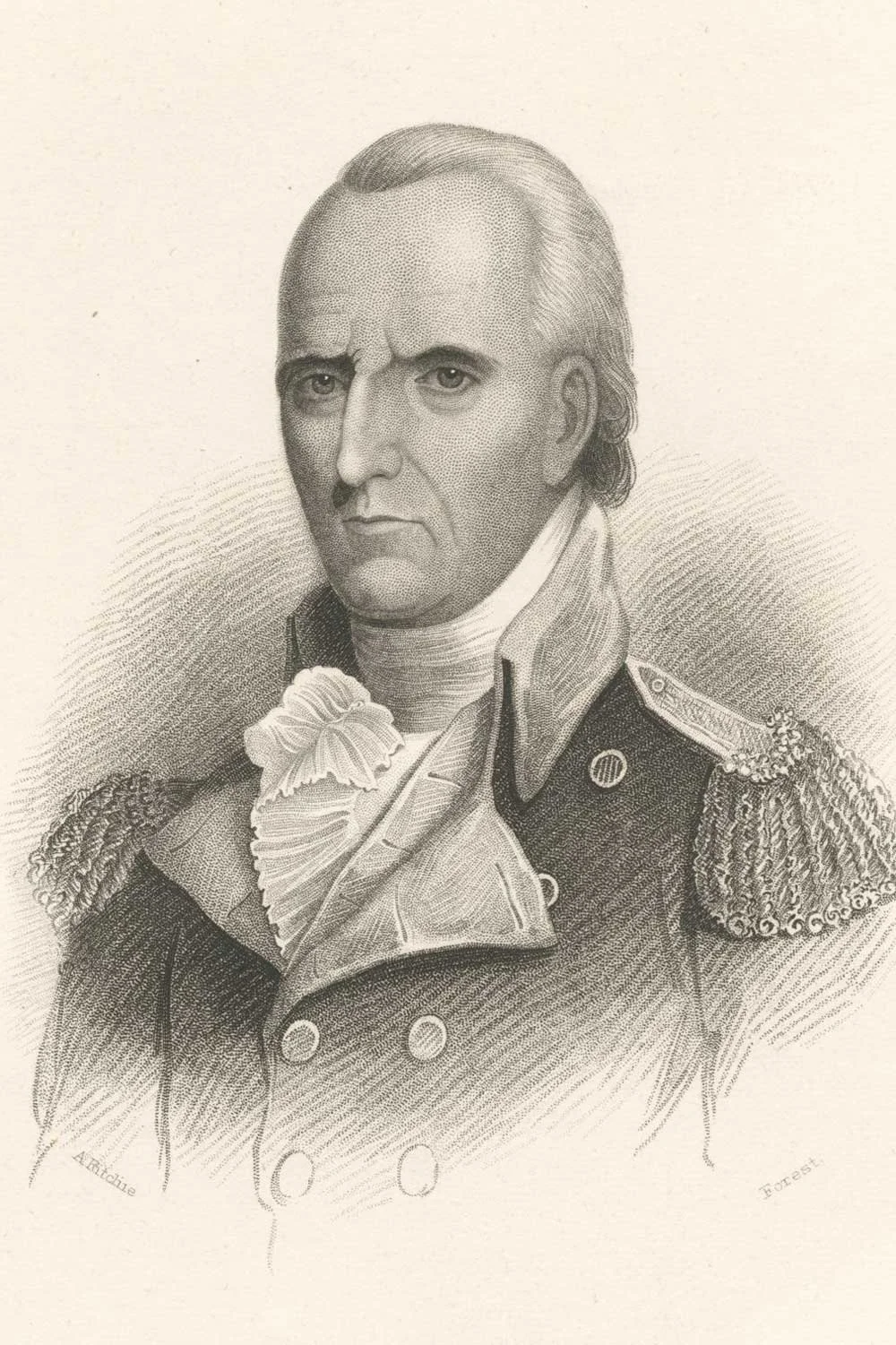

“Colonel John Stark.” New York Public Library.

With no relief coming from Howe and food supplies running low, Burgoyne dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum and 800 Brunswick (German) soldiers to capture those supplies. They did not know it, but they were walking into a buzzsaw in the form of Colonel John Stark and 2,000 angry New Hampshire militiamen spoiling for a fight.

The Battle of Bennington was fought on August 16, 1777. John Stark, a tough, talented commander with a prickly personality, on the eve of the battle, was confident of success. In an oration to his men, he declared, “There are the Redcoats and they are ours, or Molly Stark sleeps a widow tonight.”

Stark knew what he was about as his intrepid men crushed and routed Baum’s outnumbered dragoons, with Baum being mortally wounded. As the first fight was ending, German reinforcements arrived to aid Baum but it was a case of too little too late, and, as darkness fell over the battlefield, they were forced to retreat back to the main British camp.

The Battle of Bennington was an unmitigated disaster for Burgoyne. His army lost almost 1,000 men, one sixth of his entire force, while the Americans suffered only about 70 casualties, making the battle one of the most lopsided American victories of the American Revolution.

More than any other episode in the American Revolution, the Saratoga campaign was demonstrating the futility of England trying to subdue her rebellious American colonies across a broad continent by force of arms.

Next week, we will discuss the fights at Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.