Fort Ticonderoga Falls to British

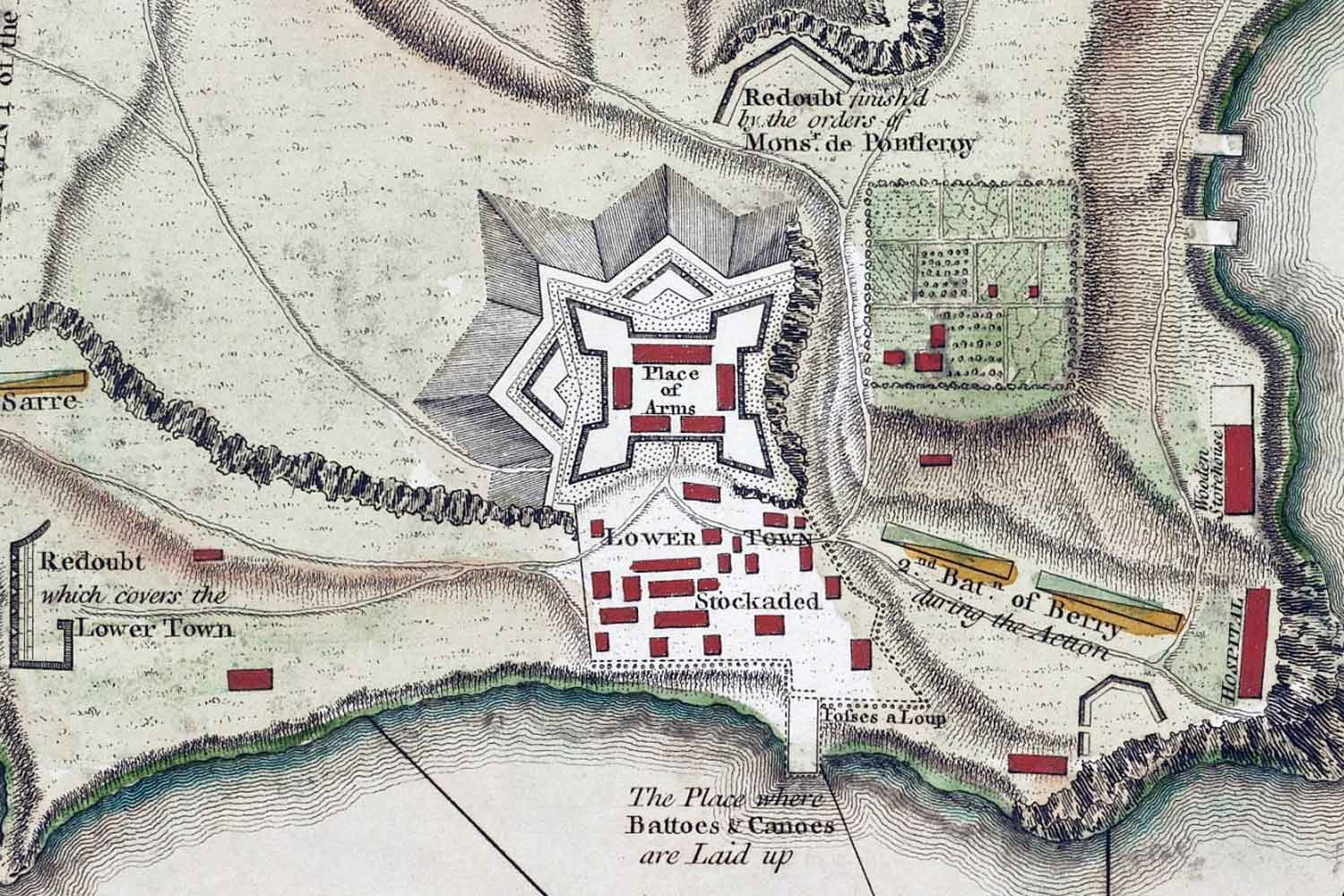

The first objective for the British task force under the command of General John Burgoyne was the capture of Fort Ticonderoga on the south end of Lake Champlain. This fortress had been the key military site in the region since its construction in 1757, and the scene of conflicts both in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution.

In the summer of 1777, Fort Ticonderoga had been in American hands since its capture by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold two years before. It was garrisoned by slightly over 2,000 men, mostly Continentals from New England like the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, under the very capable command of Colonel Alexander Scammel.

The overall command of the post was assigned to General Arthur St. Clair, an experienced soldier who previously served as an officer in the British Army, including at the Battle of Quebec in 1759. St. Clair, who only arrived at Fort Ticonderoga in mid-June 1777, saw at once that the fort was not prepared to withstand an assault by a professional army accompanied by artillery.

“Major General Arthur St. Clair.” New York Public Library.

To make matters worse, St. Clair lacked the manpower needed to adequately defend the walls of the fort and two critical pieces of surrounding high ground, Mount Defiance and Mount Independence, from which enemy cannons could reach Ticonderoga. That would come back to haunt St. Clair.

Although General Phillip Schuyler, the Northern Theater commander, estimated it would take 10,000 men to properly defend the site, no reinforcements were forthcoming because all available men were needed to guard against potential moves by General William Howe’s forces in New York City.

St. Clair also had no reliable knowledge of the size of Burgoyne’s army or where it was and when it would appear in front of Ticonderoga’s walls. Almost every scout sent out by St. Clair was either killed or force to turn back by Indians accompanying Burgoyne. It was not until the morning of June 30th when the vanguard of Burgoyne’s army of 7,000 soldiers was observed by the fort’s lookouts that St. Clair understood what he was up against.

After probing the American position for a few days, British officers saw to their surprise that Mount Defiance, the high ground which commanded Fort Ticonderoga, was unoccupied. By late afternoon on July 5, British guns were emplaced on Mount Defiance making Fort Ticonderoga, our bulwark against a British invasion from Canada, suddenly undefendable. The situation was eerily similar to General Washington forcing the British to evacuate Boston by occupying Dorchester Heights in March 1776, but this time the tables were turned.

St. Clair called a council of war with his other general officers and presented two options. They could either put up a brave but futile show by trying to withstand a siege knowing they could not win in which case the entire army would be surrendered or abandon the fort incurring the anger and disappointment of Congress for giving up without even firing a shot but save the army to fight another day.

Greatly outnumbered and now in an untenable position, the council’s opinion was unanimous to evacuate Ticonderoga that very night and quickly move south towards Albany. With the decision made, St. Clair informed his other subordinates to prepare to move. Lieutenant Colonel Udney Hay, his deputy quartermaster, asked St. Clair if he had received permission from General Schuyler to quit his post.

St. Clair replied that he had not and recognized the responsibility he was assuming. As St. Clair explained to Hay, if he defended the fort “he would save his character but lose the army” and if he retreated “he would lose his character but save his army which he was determined to sacrifice to the cause in which he was engaged.” St. Clair was correct; he was court-martialed in 1778, and, although he was cleared by the Board of Inquiry, he was never given another command in the American Revolution.

In any event, the Americans retreated in surprisingly good order given the circumstances, but the British were in hot pursuit. St. Clair entrusted the rear guard action to Colonel Seth Warner, the recently elected commander of the Green Mountain Boys. Warner was no stranger to rear guard actions, having been at Breed’s/Bunker Hill to the very end and protecting the American retreat from Canada in 1776.

Unfortunately, Warner disobeyed St. Clair’s orders to keep moving and decided the bed down for the evening as his men were exhausted after marching all day in the sweltering summer heat. Warner’s decision gave the Brits time to catch up and, on the morning of July 7, they assaulted the Americans at the Battle of Hubbardton.

After offering stiff resistance, the American lines broke when Colonel Ebenezer Francis, an outstanding regimental commander, was felled by British bullets. Warner’s decision had cost the American army over 800 casualties and further disorganized and demoralized the troops. St. Clair did the only thing he could do and ordered the retreat to continue.

For the British, the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the Gibraltar of the North, and the subsequent victory at Hubbardton, led to great jubilation. When informed of these events, King George III exclaimed, “I have beat them; I have beat all the Americans.” The good King would soon find out how wrong he was.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Bennington. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.