British Begin the Saratoga Campaign

The Saratoga Campaign of 1777 was arguably the most significant military event during the American Revolution. If the British had achieved their goals, the American colonies would have been split in two and it is very likely that our quest for independence would have failed.

Following the disastrous American invasion of Canada in 1776, British General Guy Carleton pursued the retreating Continentals until late October and as far south as Fort Ticonderoga. The approaching winter halted his advance and he wisely retired to Canada, content to wait for the following spring to renew his assault.

However, when Carleton’s report on the inconclusive result of the 1776 invasion reached Lord George Germain, England’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Germaine was not happy. Germaine, although responsible for the grand strategy in North America, had no real comprehension of the distances and natural obstacles armies encountered in America.

That did not seem to matter to Germaine for he was a man who knew what he knew. In his opinion, Carleton lacked the aggression needed to subdue the colonies. Accordingly, Germaine turned to General John Burgoyne to right the ship in North America.

Burgoyne, who was also a Member of Parliament, had been with the troops that helped relieve the siege of Quebec and had accompanied Carleton on his campaign across Lake Champlain in 1776. However, Burgoyne, unhappy with his subordinate role and feeling Carleton too timid, returned to London in December and repeatedly harped to Germaine and the King about Carleton’s perceived faults.

For all his flair and societal polish (Burgoyne was also a published playwright having written several plays) and having developed what appeared to be a solid strategic plan, Burgoyne was a relative novice compared to Carleton regarding the nuances of warfare in North America.

Carleton had first arrived in Canada in 1758 and was with General James Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham when the British captured Quebec from the French in 1759. Perhaps more importantly, Carleton had been the Governor General of Canada since 1768, was liked and well respected by the citizenry, and had commanded the invasion of 1776.

In comparison, Gentleman Johnny, as Burgoyne was called, had spent only one short season in country. That brief period did not give Burgoyne, a man who was nothing if not self-assured, a full appreciation for the logistical challenges the upcoming campaign would present. This lack of experience and distain for all things colonial, especially the soldiers, would prove fatal to the enterprise.

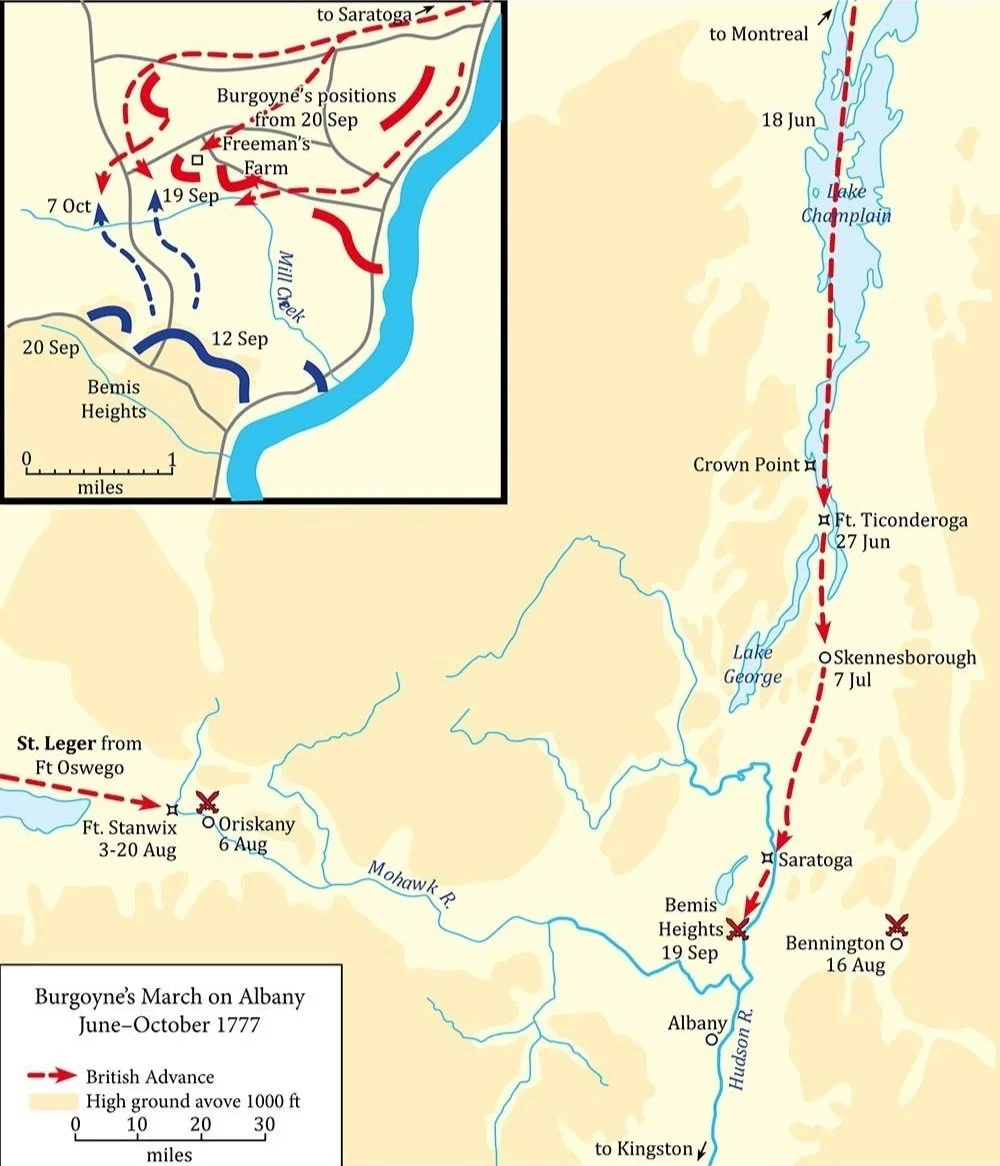

In Burgoyne’s defense, he did conceive a convincing plan to divide and conquer the colonies, and he pitched it to all who would listen. The general idea was to gain command of the water highway stretching from Montreal in the north to New York in the south, running the length of Lake Champlain and connecting to the Hudson River via a short portage.

If successful, this plan would create an impenetrable obstacle for the Americans to overcome and split New England off from the other colonies; thus, allowing the British army to defeat the two rebellious sections one at a time.

Map of Burgoyne’s March on Albany. Wikimedia.

Tactically, the concept called for Burgoyne to march south from Montreal to Lake Champlain, and then sail up the lake to assault and capture Fort Ticonderoga, and finally to continue to Albany. Meanwhile, British forces in New York, under Sir William Howe, would move north up the Hudson River to rendezvous with Burgoyne.

To further divide and confuse the American army, Burgoyne’s plan also called for a third force led by Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger to sweep east from Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario to the Mohawk River Valley and then continue towards the meeting point in Albany.

The one issue Burgoyne did not adequately address with Germaine before leaving London for Canada, or for Germaine to make crystal clear to Burgoyne and General Howe in New York, was the command structure of the three-pronged advance once the expedition commenced. General Howe, as the Commander of British land forces in North America, held the highest rank on the continent and nominally called all the shots regarding military operations on the continent.

However, for Burgoyne’s plan to succeed, Burgoyne would need Howe to subordinate his own wishes and plans to those of Burgoyne. Given the temperament of Lord Howe, a prickly sort of man and one who was not particularly fond of Burgoyne, this expectation was perhaps not very realistic. In any event, Burgoyne certainly had the impression that General Howe’s primary mission, at least during this campaign, was to move up the Hudson in support of Burgoyne.

On June 20, 1777, Burgoyne and his command of 7,000 men, roughly half British regulars and half Germans from Brunswick and Hesse-Hanau, set sail in their tiny armada from the north end of Lake Champlain. Because Carleton had cleared the lake of American gunboats the previous year, the passage was smooth and unencumbered. In Burgoyne’s mind, he was a few months and one easy campaign away from being the toast of London.

Next week, we will discuss Burgoyne’s advance to Fort Ticonderoga and beyond. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.