Continental Army Victorious at Princeton

General George Washington and his Continentals had achieved a great victory at Trenton on December 26, but the General saw another opportunity if he acted aggressively. On December 30, he recrossed the Delaware hoping for another miracle.

By then, Colonel John Cadwalader and his Pennsylvania troops had finally crossed into New Jersey and the local militia had been roused to action, giving Washington about 5,000 men under his command. Unfortunately, the enlistments of many of these troops were set to expire the very next day, December 31, at midnight.

To ensure he did not lose any of these veterans, Washington assembled the men and offered them an extra $10 in return for six more weeks of service, but none accepted this offer. Washington, not prone to giving inspirational speeches, then appealed to their sense of duty.

He declared, “My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected; but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay only one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty and to your country which you probably never can do under any other circumstances.” Almost all soldiers signed up for the extra month.

Meanwhile, Lord Charles Cornwallis had assembled an army of about 6,000 men and was marching towards Trenton to strike back at the bold Americans. When Cornwallis reached Princeton, about twelve miles north of Trenton, he left a contingent there under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood. On January 2, 1777, Cornwallis continued marching towards Trenton where he hoped to attack the Continentals that morning.

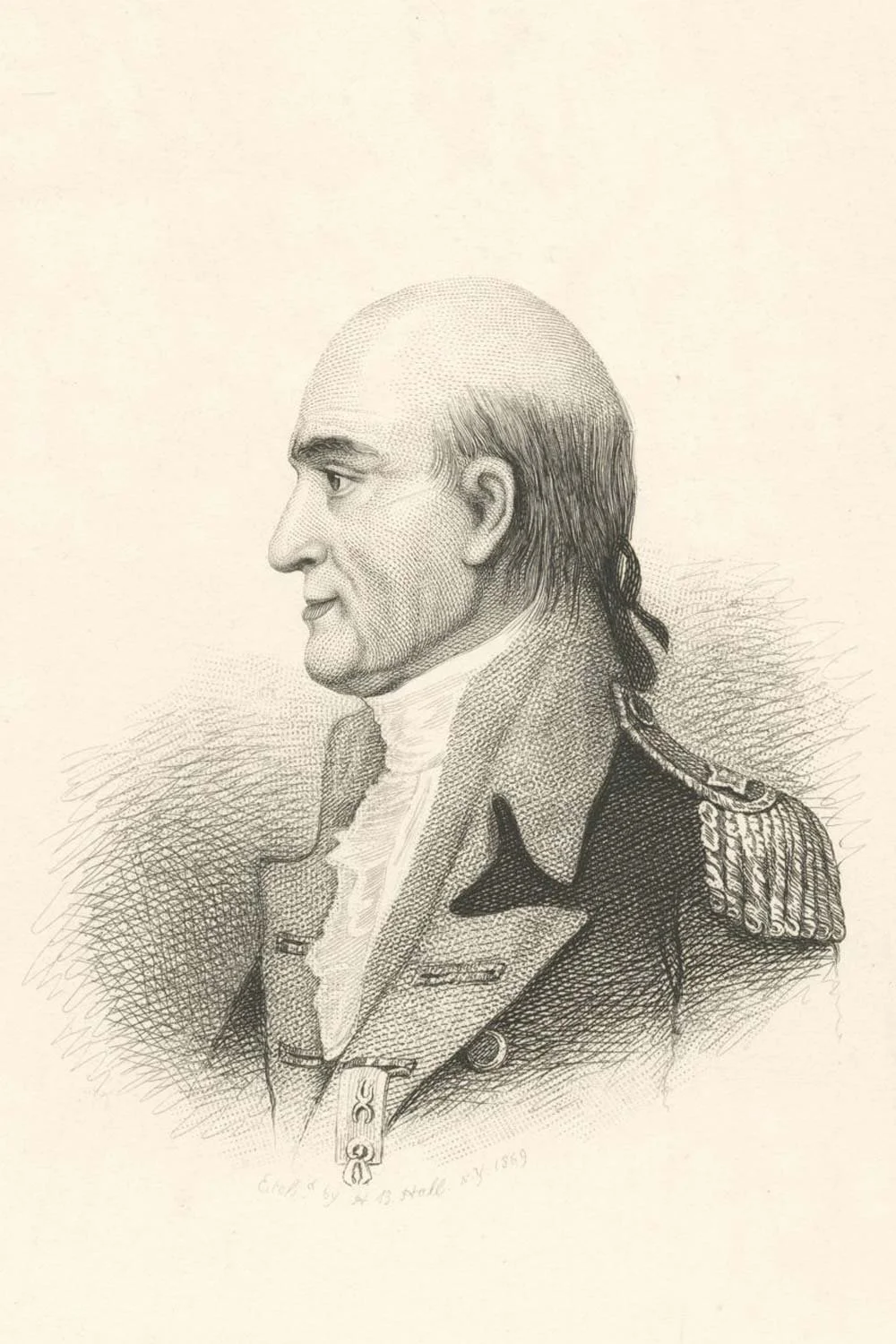

“Edward Hand.” New York Public Library.

Instead, prior to reaching Trenton, he encountered determined American troops led by Colonel Edward Hand, who had been tasked by General Washington to delay Cornwallis’ advance as long as possible. Hand and his American riflemen performed brilliantly and kept the Redcoats at bay until late in the afternoon. When Cornwallis finally reached the outskirts of Trenton, he found the Continental Army dug in on the south side of Assunpink Creek.

Eager to punish the American upstarts, Cornwallis immediately ordered an attack, but the determined Americans repulsed the Redcoats. Twice more Cornwallis sent his men forward, but musket fire and Colonel Henry Knox’s ever efficient artillery fire forced the British to retreat to the safety of their lines.

Rather than risk more losses that night, Cornwallis decided to wait until morning when he would be reinforced by Colonel Mawhood and his troops stationed at Princeton. Although advised by some of his staff that the ever-elusive Washington may not be there in the morning, Cornwallis stated, “We’ve got the old fox safe now. We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.” As it turned out, Cornwallis should have heeded his subordinate’s advice.

Learning that the Quaker Bridge Road went around the British left flank, Washington moved out on it around 2:00am on his way to attack Mawhood’s contingent at Princeton. To hold Cornwallis in place and mask his movement, Washington left behind 500 men to make noises by digging with picks and shovels and keep the campfires burning. At dawn on January 3, Cornwallis discovered Washington had slipped away.

Meanwhile, Mawhood, as ordered, had begun to march south to reinforce Cornwallis in Trenton. While enroute, he ran into the Continental Army’s lead element under General Hugh Mercer. British bayonets soon killed Mercer and drove the Americans from the field. With the Continentals fleeing and the day seemingly lost, General Washington arrived on the scene.

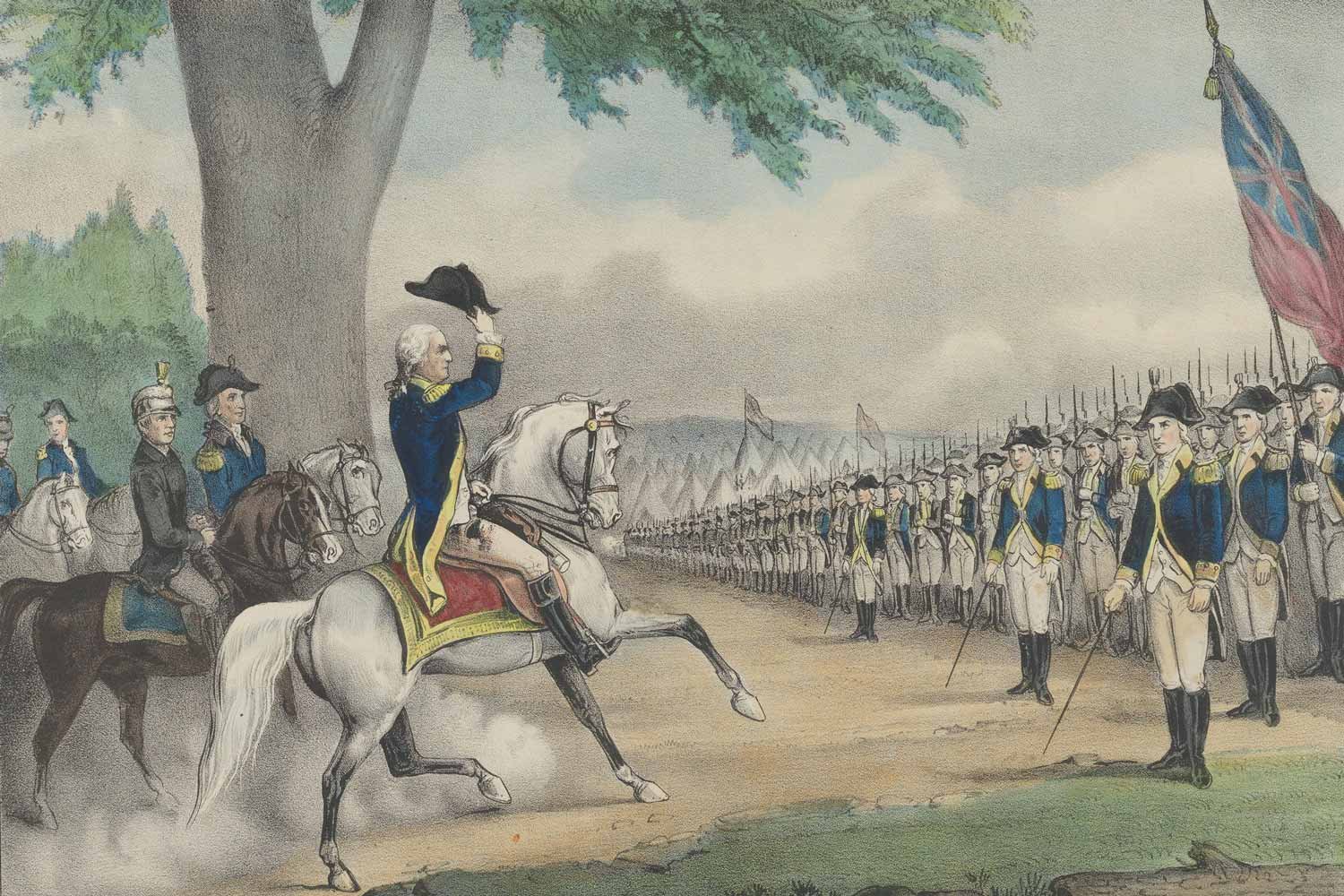

Mounted on a large white horse and conspicuous in his uniform, General Washington rode to within 30 yards of the British lines as he rallied the men, shouting, “Parade with us my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy and we shall have them directly.”

Inspired by Washington’s courage, the American gained heart, reformed their ranks, and drove against the Redcoats. Now the roles were reversed, and the pursuers became the pursued. Washington likened the British retreat to a “fine fox chase” and a portion of his force harassed the fleeing Redcoats until dusk.

When the smoke cleared the Continental Army had achieved another great victory. The Americans held the field of battle and had inflicted 170 casualties on the British and captured another 280 while only losing forty men.

Discouraged by the American’s success and willing to wait for springtime before renewing his campaign, British General William Howe ordered Cornwallis into winter quarters a second time. General Washington moved his men to the hills around Morristown, New Jersey to keep an eye on the British and rest and regroup his forces.

After six months of active campaigning, the British Army, the finest in the world, was only in control of NY and a few towns in NJ. Washington’s heroic perseverance and incredible will had kept the army together as a formidable fighting force, and his daring and field generalship in these two victories at the close of this first campaign saved the American cause. Our young nation had a reason to cheer.

Next week, we will discuss how the British captured our capital of Philadelphia in 1777. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.