A Desperate Winter at Valley Forge

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.

Valley Forge was so named because of the many ironworks and pre-industrial facilities located alongside Valley Creek, a tributary of the Schuylkill River. The spot selected by Washington for his winter encampment was about 18 miles from Philadelphia, allowing the Continental Army to keep an eye on British forces in the city. Importantly, it was strategically placed on high ground above the creek valley, providing a strong, natural defensive position.

Unfortunately, there were no ready-made shelters for his 12,000 soldiers and improvised wooden huts were hastily erected. Within four weeks of the Army’s arrival, over 2,000 shelters had been erected, each housing 8-12 men. The quality of the buildings varied, but most barely kept out the wind and cold and they lacked adequate ventilation for removing woodsmoke from the fires used for heating and cooking.

Clothing was in short supply and many men wore rags and thread-bare clothing, and a significant number had no shoes. So poorly clad were the men, that many dared not venture outside their miserable huts. The prescribed daily allotment of food was rarely met with the men having no meat for days on end and a complete dearth of vegetables. Additionally, critical medicines and medical supplies were practically non-existent.

The core issue was a lack of leadership. The job of Quartermaster General, charged with supplying the Continental Army, had been entrusted to General Thomas Mifflin, a former politician from Pennsylvania. However, Mifflin was not up to this very challenging assignment and resigned his post amid deep criticism in late 1777.

Congress failed to fill this vital post and the supply chain floundered badly, with the brave soldiers paying the price. That terrible winter, thanks to a bickering and seemingly indifferent Congress, about 2,500 troops died of disease, exposure, and hunger.

Washington, who remained at Valley Forge with his troops throughout this long winter, sent almost daily entreaties to Congress imploring them to alleviate his men’s suffering. In December, he wrote to Henry Laurens, then President of the Continental Congress, “unless more vigorous exertions and better regulations take place in that line (supplies) and immediately, this army must dissolve.”

At this critical juncture, Washington turned to General Nathanael Greene, a division commander and one of his most trusted subordinates, to remedy the quartermaster issues. Greene attacked this task with his customary zeal and competence, and supplies immediately began flowing to the army.

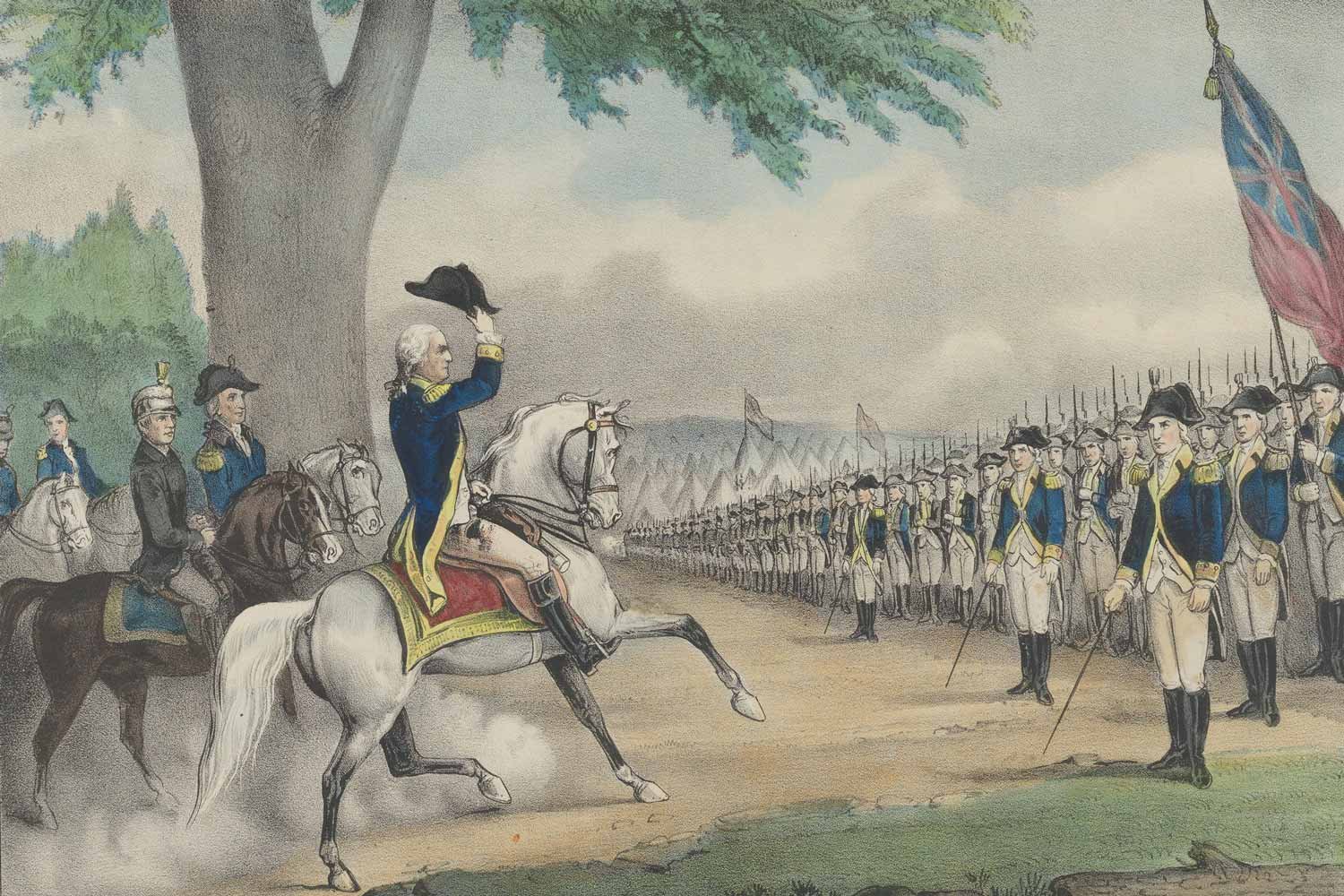

Edwin Austin Abbey. “Baron von Steuben Drilling the Troops.” Wikimedia.

Training was another area in which the Continental Army was deficient. That began to change on February 23, 1778, when Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben, better known as Baron von Steuben, arrived at Valley Forge. The Baron had been an officer in Frederick the Great’s Prussian Army but was temporarily out of work in Europe.

Arriving in America, von Steuben immediately applied to Congress for a position, and he was assigned by General Washington as the Continental Army’s Inspector General. The Baron surveyed the condition of the men and the deplorable state of the encampment at Valley Forge and was appalled by what he saw. He quickly implemented a strict training program that would transform the regiments into an army that could stand up to any European force.

Von Steuben stressed the essentials of drill, use of the bayonet, and most importantly, emphasized that officers were responsible for their men. Within a month, the army was parading like veterans and taking pride in their mastering of the soldier’s way. These parade ground maneuvers would yield dividends in the campaigns to come.

In the Spring of 1778, word of the Treaty of Alliance with France arrived in America, and American’s hopes soared. By this time, British General William Howe had been replaced by General Henry Clinton who was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia, which he did on June 18, 1778, and return to New York City.

Washington, always a fighter, was not content to simply let him go and attacked the British rear guard at Monmouth Courthouse in New Jersey on June 28, 1778. Although the battle started poorly for the Americans, Washington saved the day by taking personal command of the regiments and stiffening their resolve.

Although the fight ended in a draw, under Washington’s leadership the men performed well and showed the battlefield discipline instilled in them by Baron von Steuben. What had been a poorly equipped and inadequately trained group of men when it entered Valley Forge six months before had proven it could stand up to the British army.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.