Washington and Continental Army Face Rocky Start

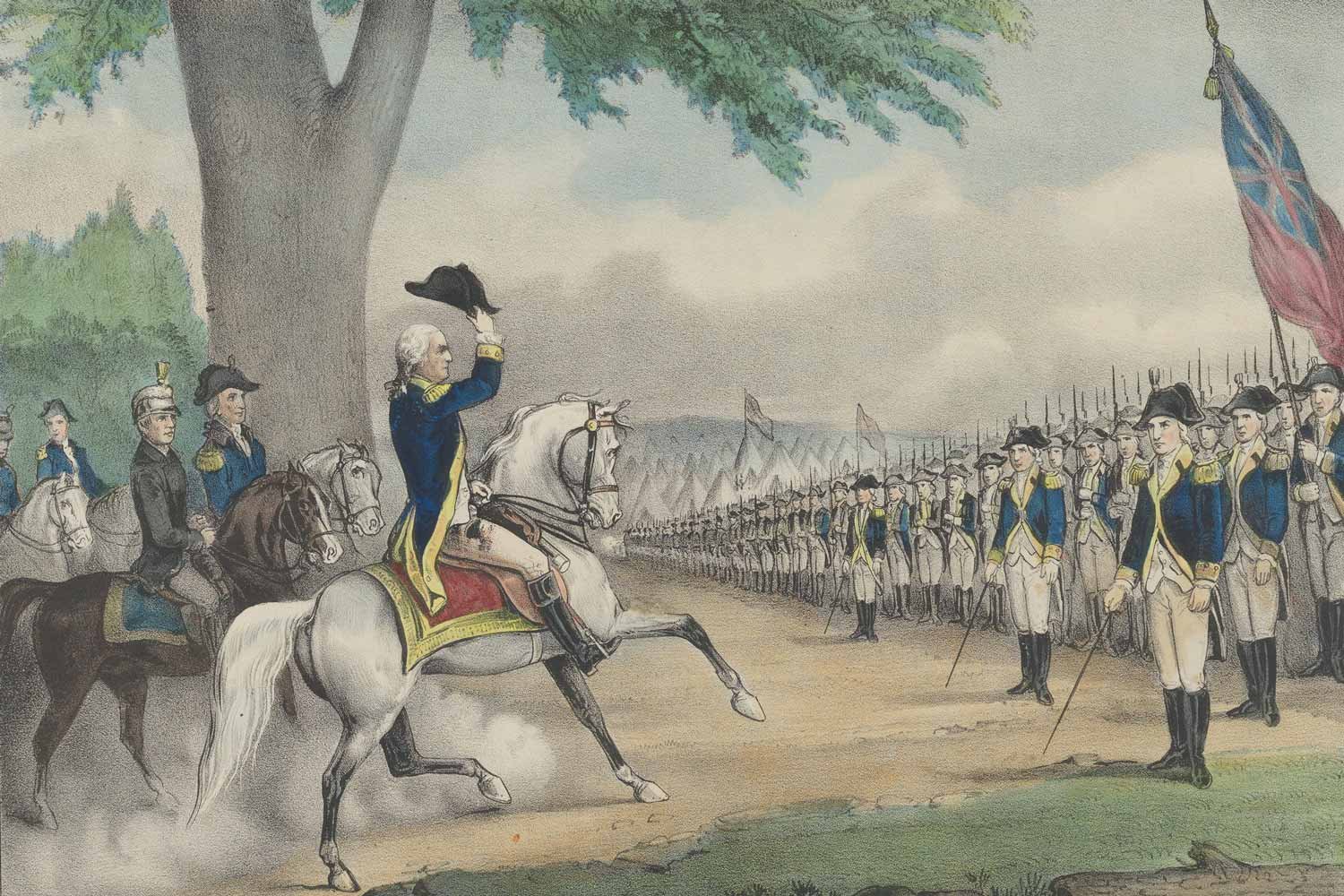

General George Washington formally took command of the Continental Army surrounding Boston on July 3, 1775. He immediately began to organize and train the troops and his natural aggressiveness was soon on display.

In November 1775, Washington dispatched General Henry Knox to Fort Ticonderoga to bring siege guns that had been captured there in May to Boston to use against the British. Once these heavy guns were emplaced on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston Harbor, the English position became untenable and the commander, General William Howe, evacuated the town on March 17, 1776. We had achieved our first great victory.

The British Army eventually ended up in New York, but Washington had anticipated that move and he was there with the Continental Army to greet them when they arrived. Unfortunately, Washington’s forces were outnumbered and outgeneraled and the Continentals lost Long Island when the British out flanked them at the Battle of Brooklyn Heights on August 29, 1776.

The 9,000 Continentals were trapped hard against the East River by Howe’s 20,000-man force and the end seemed near for the Americans. While Howe prepared for a siege, Washington planned his escape. Fortunately, a providential fog set in that night which allowed Colonel John Glover and his regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts, mostly seafaring men, to ferry Washington’s army across to Manhattan Island undetected by the British.

In keeping with Washington’s extraordinary sense of duty and leadership, the General was the last man to enter the last boat leaving for Manhattan. Incredibly, this perilous enterprise done in the dead of night and in the face of 20,000 British troops on land and the cream of the British navy nearby in the Hudson River, was completed with no loss of life.

“General John Glover.” New York Public Library.

Once on Manhattan, Washington positioned about 8,000 Connecticut militiamen at Kip’s Bay to repel the expected British invasion. On September 15, General Howe launched his amphibious assault there but, at the first sight of the Redcoats, the inexperienced militia melted away without firing a shot.

With his flank completely exposed to the British, General Washington was forced to retreat to Harlem Heights in upper Manhattan, where he established a strong position. The next day, Howe’s forces, confident of success, attacked the Continental line but were repulsed. This marked General Washington’s first battlefield victory and helped restore some confidence in the men.

Following this unexpected resistance, Howe sat idle for over a month trying to find a way to force Washington out of his strong position without a frontal assault. On October 18, Howe was able to land a force at Pell’s Point and potentially trap the Continental Army on Manhattan. General Washington quickly moved his troops to White Plains, just north of Manhattan.

On October 28, Howe attacked the Continentals and, although the Americans fought well, drove them from their position just outside of White Plains. Washington reestablished his camp near North Castle, but Howe chose to not attack due to his mounting losses.

Instead, Howe turned south and reentered Manhattan to assault a 2,400-man force at Fort Washington under the command of Colonel Robert Magaw. While Washington recognized the danger to this garrison, he allowed Magaw and General Nathanael Greene, Magaw’s immediate superior, to make the decision on evacuating the fort. They chose to stay, and the entire garrison was captured by Howe’s Redcoats on November 16. It would prove to be one of the costliest losses of the war for the Continentals.

Washington now had no choice but to cross the Hudson River, which he did at Peekskill, and head south into New Jersey to escape the British army. Retreating through New Jersey towards Philadelphia, Washington and the remnants of the army crossed into Pennsylvania in December 1776 and wisely ordered his men to seize all the boats in that vicinity along the Delaware to prevent a crossing by the British.

At that point, General Washington’s command had dwindled down to roughly 3,000 poorly clad, poorly fed, and poorly armed men. Thinking the end was near, General Howe retired to the warmth of his house in New York City and placed his soldiers in winter quarters. But Howe did not appreciate or understand the perseverance of George Washington. He would soon realize his mistake.

Next week, we will discuss Washington crossing the Delaware and the ten crucial days that saved the American Revolution. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.