George Washington Enters Politics

As befitting a wealthy landowner in colonial Virginia, George Washington became active in the colony’s politics in the 1750s. He first ran for a seat representing Frederick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1755 but lost the election, finishing third behind Hugh West and Thomas Swearingen. Interestingly, it was the only political race he would ever lose. Washington ran for that same seat in 1758 and was victorious, and he held this seat for seven years.

Washington was a moderate during his time in the legislature and took a measured but critical approach of English policies such as the Stamp Act in 1763. He even voted in favor of Patrick Henry’s famous resolutions denouncing the King and Parliament’s rights to lay internal taxes on the colonies. While calling Parliament “our lordly masters” and saying they “will be satisfied with nothing less than the deprivation of American freedom,” he also believed we should not be rash.

Louis Mathieu Didier Guillaume. “George Mason.” Encyclopedia Virginia.

In a 1769 letter to George Mason, Washington stated, “something should be done to…maintain the liberty which we have derived from our Ancestors”, but that armed resistance “should be the last resource.” Characteristically, Washington was initially cautious in his approach to dealing with the approaching crisis.

On December 16, 1773, the Sons of Liberty threw 92,000 pounds of East India Tea into Boston Harbor. This wanton destruction of private property was widely condemned including by firm defenders of American rights like Washington who contended that the East India Company should be reimbursed for their losses.

However, King George and his ministers made matters worse and an accommodation impossible by quickly passing the Coercive Acts in 1774 which closed Boston Harbor and revoked the charter of Massachusetts, measures which Washington felt were extreme. At this point, Washington began to see independence as an acceptable course to take.

To Britain’s surprise, most Americans in other parts of the country rallied to the side of Massachusetts. What could happen in New England could happen elsewhere. It did not help that Parliament also passed the Quebec Act in 1774 which allowed for the expansion of Roman Catholicism into the lands beyond the Appalachians, much of which was owned as an investment by Virginians like Washington.

While many urged patience and conciliation with England, Washington was no longer in that camp. In a letter to his friend, Bryan Fairfax, Washington stated emphatically that the cause of Massachusetts was the cause of America. He saw little reason to petition the King and perceived a persistent attempt by England to tax for revenue. Washington stated to Fairfax, “I think the Parliament of Great Britain has no more right to put their hands in my pocket, without my consent, as I have to put my hands into yours for money.”

To pressure Parliament to rescind the Coercive Acts, Washington and other Virginians pushed for a total boycott of British goods and called for a convention of all colonies to organize their efforts. Leaders in Massachusetts issued a similar call, and the result was the First Continental Congress which convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774.

Virginia selected seven patriotic stalwarts to represent the colony, including Peyton Randolph, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and George Washington. While Washington was not a gifted speaker nor a man educated in constitutional matters, he nevertheless was widely respected when he spoke and considered a man who could be trusted with power.

Moderates like John Dickinson controlled the day at the First Continental Congress. Rather than making any harsh declarations, it was agreed to form the Continental Association which initiated a boycott of British goods and to send a Petition to the King outlining the colonies’ grievances. They also made plans to meet again in the summer of 1775 if these measures were not successful.

On April 19, 1775, the American Revolution began with “the shot heard round the world” at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. When the dust settled, there were about 16,000 militiamen surrounding the British Army in Boston, but they needed to be organized and they needed a capable leader.

The next month, on May 10, when colonial delegates convened in Philadelphia at the Second Continental Congress, deciding what to do with this instant army and choosing the right man to lead it was foremost on their mind. Virginia had again selected George Washington as one of its delegates and he was soon under everyone’s eye.

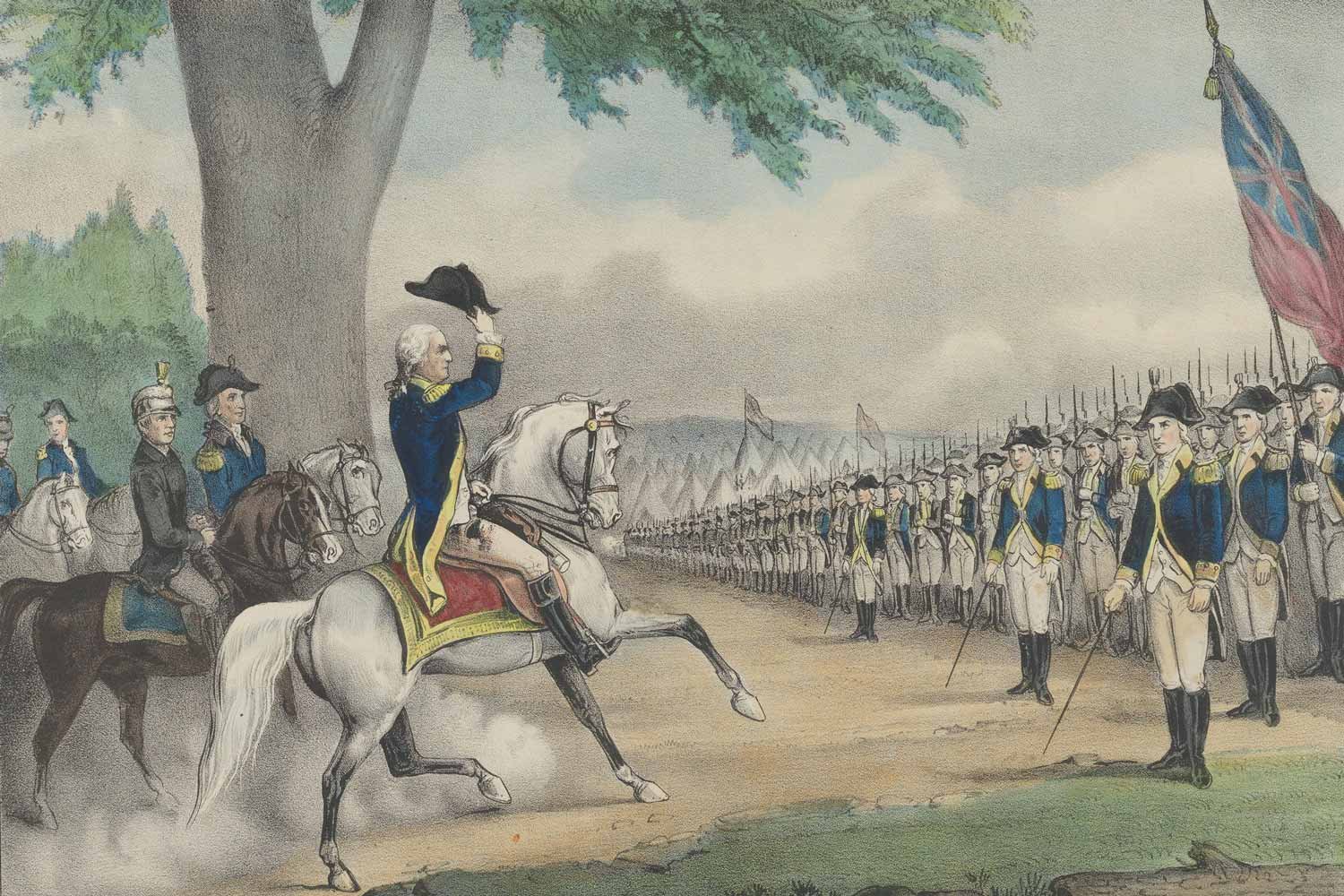

On June 14, 1775, Congress “adopted” the New England militiamen assembled near Boston and created the Continental Army. The next day, John Adams nominated George Washington as the “General and Commander in Chief of the Army of the United Colonies” to lead us to victory on the battlefield and he was unanimously elected.

Washington was seen as the obvious choice. He had proven himself to be brave in battle in the French and Indian War, his virtue was above reproach, and his devotion to the cause was unquestioned. At a previous meeting, Washington had declared he would “raise one thousand men, subsist them at my own expense, and march myself at their head for the relief of Boston.”

General Washington briefly addressed Congress in accepting his appointment. He announced he would not accept any pay for his services, but asked Congress to cover his expenses. Washington also declared he “would exert every power I possess” to further “the glorious cause”, but warned “I do not think myself equal to the command.” Time would demonstrate Congress had made a wise choice. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.