The Life of Martha Washington

Martha Washington was our nation’s first First Lady and lived in the shadow of her larger-than-life husband George. However, most Americans do not realize that she was a very capable woman and, when given the opportunity, managed her own affairs quite well.

John Wollaston. “Martha Dandridge Custis.” Washington and Lee University.

Martha was born on June 2, 1731 at Chestnut Grove, a plantation in New Kent County, Virginia. Her father was John Dandridge, a Virginia planter and politician, who had emigrated from England in 1730. Soon after arriving in America, Dandridge married Frances Jones and they had eight children together, with Martha being the oldest.

In keeping with the times, Martha did not receive much in the way of a formal education. Instead, she was taught housekeeping, religion, music, needlework, and dancing, and she learned to read and write. As an adult, Martha spent about one hour each day reading the Bible and praying.

By the time Martha turned 16, she had caught the eye of Daniel Parke Custis, a 37-year-old well-to-do planter from New Kent County and a vestryman at St. Peter’s Church where Martha attended services. Despite initial disapproval of the match from his father, Custis courted Martha for two years and they got married on May 15, 1750.

Daniel and Martha had four children together at their plantation called White House but two of them did not survive childhood. Custis died unexpectedly, probably of a heart attack, in 1757. His death left the 26-year-old Martha a very young and wealthy widow with two children, a 17,500-acre plantation to manage, and responsibility for almost 300 slaves.

After the normal mourning period, Martha’s parlor at White House became the destination of many unmarried men in Virginia, including a tall Colonel of militia named George Washington who owned the nearby Mount Vernon estate. Washington made two visits to Martha’s plantation in March of 1758 and the mutual attraction was immediate. By the second visit, the two young people had reached a decision to plan their life together.

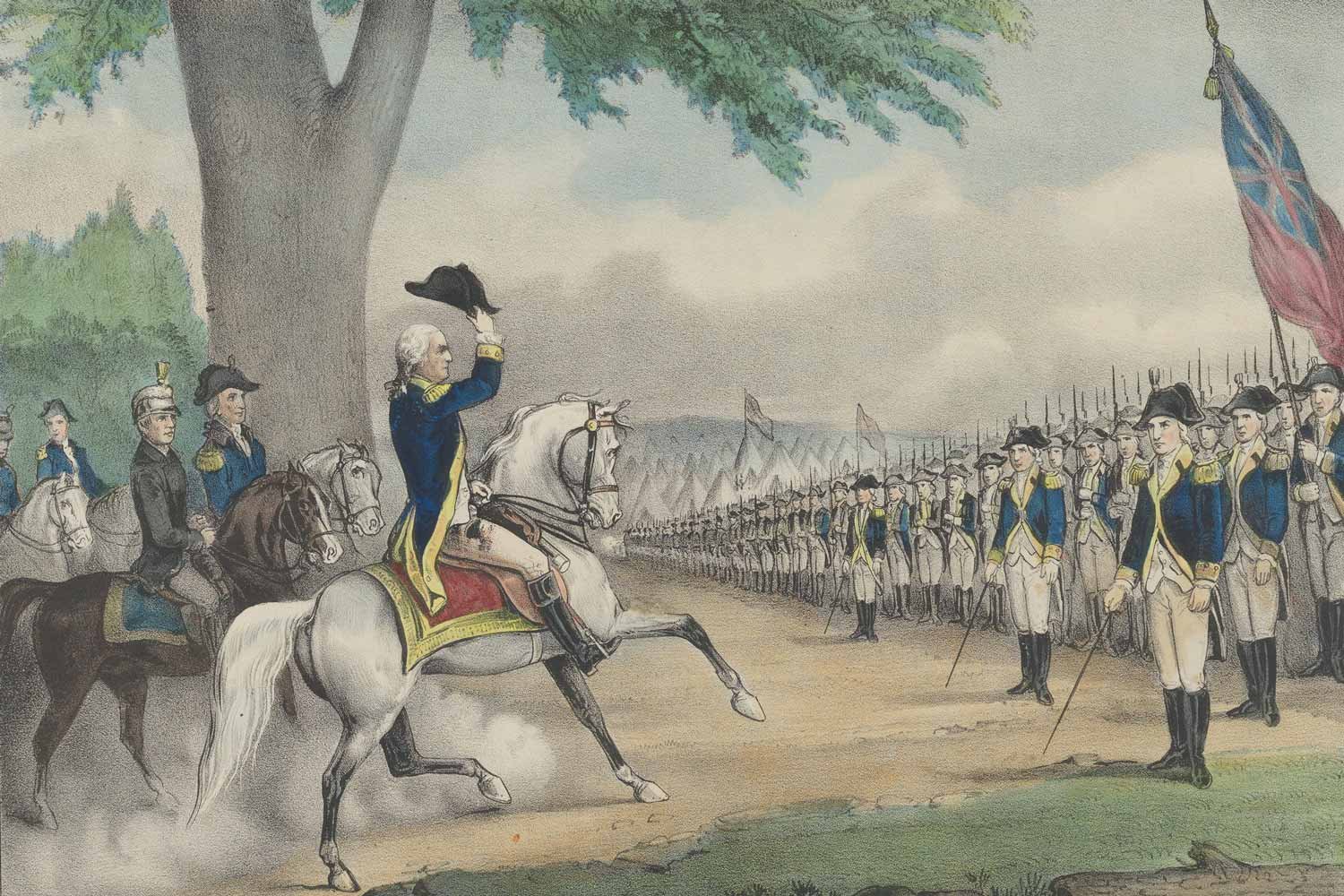

A 19th-century historical scene of Martha Custis and George Washington courtship.

Interestingly, Martha must have instinctively trusted, as well as loved, George. Despite prenuptial agreements to protect assets from a previous marriage being common in 18th century America, Martha did not require any sort of agreement to protect her assets from the Custis marriage.

George and Martha were married on January 6, 1759, at her home in New Kent County, and soon moved to Mount Vernon. While George oversaw operations on their plantations, Martha was responsible for the management of the house. They lived a fairly quiet life for the first decade or so of their marriage, with George getting involved in local politics and Martha hosting numerous guests each year.

As relations between England and her American colonies began to deteriorate in the early 1770s, George was pulled into the national spotlight and away from Mount Vernon. On June 15, 1775, he was named the Commander of the fledgling Continental Army then surrounding the British Army in Boston, and he immediately set off for Massachusetts. Although he and Martha did not know it at the time, they would spend most their remaining years away from Mount Vernon.

General Washington and his Continentals had eight winter encampments, starting with the one in 1775 in Boston. Washington’s sense of duty compelled him to remain with his men throughout each of these harsh winters instead of returning to the comfort of Mount Vernon. Martha’s matching sense of duty compelled her to also give up the comforts of home and join the General at these encampments every year. In camp, Martha knitted for the soldiers, visited hospitals, and helped raise money to purchase shirts and other supplies for the men.

During the growing (and military campaigning) season each year, Martha returned to Mount Vernon to help manage the estate, with the assistance of George’s cousin, Lund Washington. By all accounts, Martha was very capable and fiscally prudent.

When the War ended, George returned to Mount Vernon and the Washington’s domestic life resumed some sense of normalcy. That all changed in 1789 when America called again and named George as our first President, making Martha our first First Lady. Interestingly, that title was not used during Martha’s lifetime with people referring to her as Lady Washington.

In her role, Martha hosted Friday evening receptions open to members of Congress, visiting dignitaries, and men and women from the local community, both in New York and Philadelphia after the capital moved there in 1790. She was a gracious and dignified hostess and a great fit for her noble husband.

At the conclusion of President Washington’s second term in March 1797, the Washington’s returned to Mount Vernon, hoping for a long, well-earned retirement. Unfortunately, George caught a cold while out riding one day and died on December 14, 1799. Martha was too grief stricken to attend the funeral.

Martha Washington died on May 22, 1802 and was laid to rest next to her beloved George in the family crypt at Mount Vernon. Lady Washington lived a fuller life than most of us can even imagine, and she lived it in a manner that brought great honor to herself and her country.

Next week, we will discuss George Washington entering the political arena. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.