The British Capture Philadelphia

Our nation’s capital has twice been captured by a foreign army and in both cases, it was by British Redcoats. The more famous incident was the burning of Washington on August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812. However, the first occurred 37 years before that event, in 1777, when the British captured Philadelphia, the capital of newly independent United States.

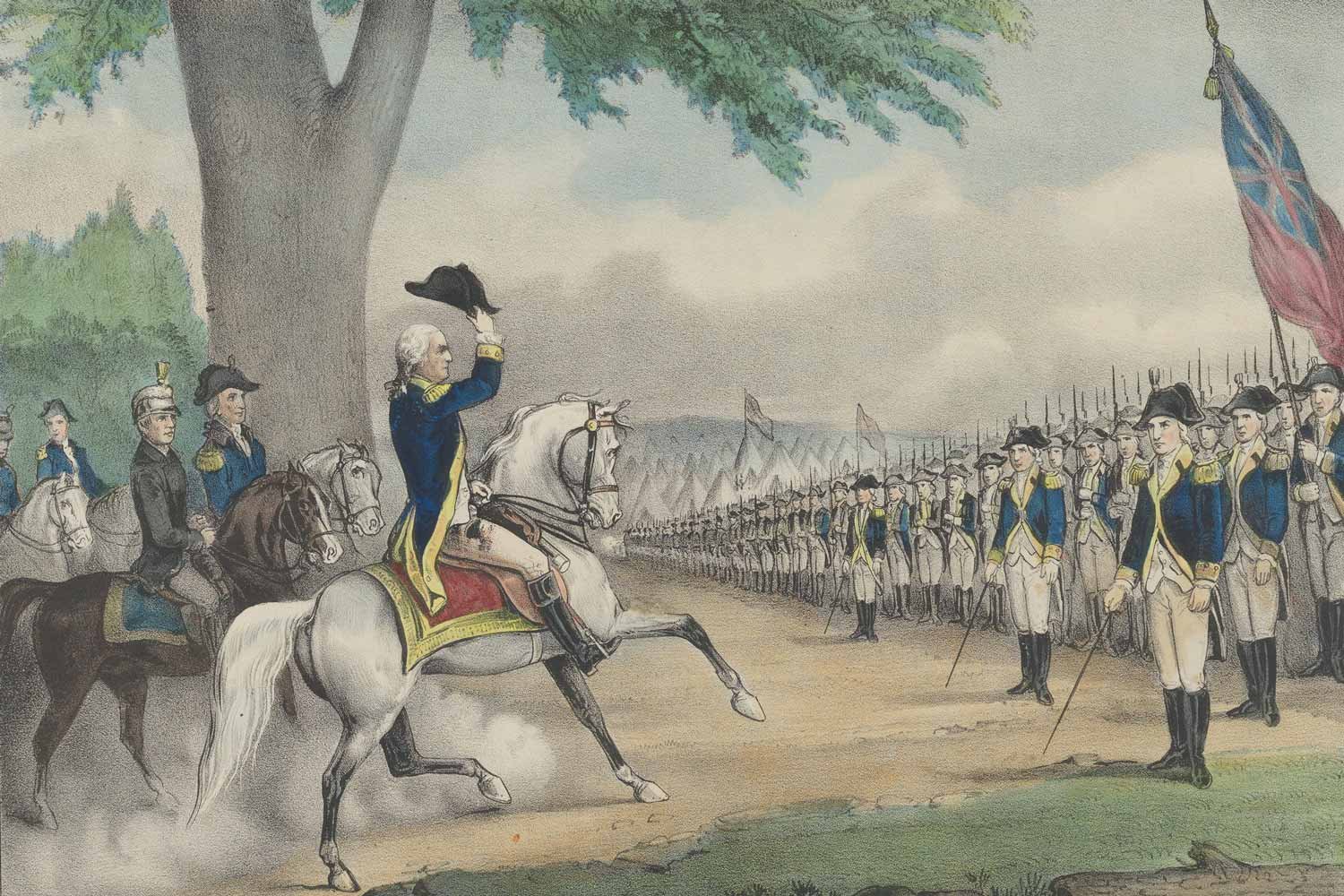

In the spring of that year, General William Howe, the commander of English forces in North America, and most of his British army were stationed in and around New York City. Howe and his men were fresh off a mostly successful campaign in 1776 in which they had defeated General George Washington and his Continental Army at almost every turn, except late in the year at Trenton and Princeton.

Howe decided his next move would be to attack Philadelphia, the largest city in the colonies and home of the Continental Congress. Rather than march overland through New Jersey, Howe opted to sail his 10,000-men from New York to Philadelphia, ultimately moving up the Chesapeake Bay and landing them in late July 1777 on the Maryland shore, at Head of Elk (today’s Elkton), sixty miles south of Philadelphia.

Washington, uncertain of Howe’s intentions, kept some units near New York City and the rest at posts in New Jersey to keep an eye on his adversary. When the English sails were spotted in the Chesapeake Bay in mid-August, Howe’s plans came into focus and Washington knew the intended target was our capital.

General Washington quickly moved to get between Howe’s soon-to-be landed army and Philadelphia. He chose to deploy his 11,000 Continentals and militiamen along Brandywine Creek, a deep, narrow creek valley, and a significant tributary of the Christina River in southeast Pennsylvania. Guessing another General’s intentions is never easy and, in this case, General Washington guessed wrong.

He decided to strongly defend Chadd’s Ford, a well-chosen position, but ignored other crossings further upstream; naturally, that is where the British attacked on September 11, 1777. Lord Charles Cornwallis went around the American lines and swept in from the north. Washington and his generals were caught unawares, but immediately moved to remedy the precarious situation.

The Battle of Brandywine Creek lasted most of the afternoon, but much of it was spent with the British constantly pushing back the Americans. Washington reacted well to the developing situation, doing his best to save his army and salvage the day. By nightfall, with both sides exhausted, Washington completed an orderly withdrawal to Chester, and the Redcoats slept on their arms.

The Redcoats and Continentals maneuvered for position over the course of the next two weeks and had two minor engagements. The Battle of the Clouds was a battle that was over almost as soon as it started due to a torrential downpour that ruined most of the powder cartridges and made roads unpassable.

Xavier della Gatta. “Battle of Paoli.” Museum of the American Revolution.

The other fight was the Battle of Paoli in which the British launched a surprise assault the night of September 20 on General Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvania Division. Caught completely off-guard, Wayne’s unit was routed by the Redcoats and lost almost 300 men to only 11 casualties for the British.

Washington now found it too risky to both preserve his army and defend the city, and wisely chose the former course of action. He informed Congress of his decision and they quickly packed up everything they could carry and headed west to York, Pennsylvania.

On September 26, 1777, the English army, led by General Howe, marched unopposed into Philadelphia and captured our nation’s capital. Although some Loyalists like Joseph Galloway were happy to see the Redcoats again, it was hardly a warm welcome. Patriots in the city were forced to choke down their anger and wait for better days ahead.

After leaving a garrison of 3,000 men in the capital, Howe bivouacked his remaining 9,000 soldiers in Germantown, about ten miles north of the city. Thinking the Continental Army was no longer much of a threat, Howe did not dig any entrenchments. He clearly did not understand the fighter in General Washington.

With Howe’s army divided, Washington saw an opportunity to attack and did so on October 4, 1777. His complicated plan ran into difficulties early in the fighting and General Cornwallis was able to reform his lines and successfully counterattack. The Continentals were forced to withdraw but had performed well at the Battle of Germantown.

Although Washington’s army lost two battles, they stood up to the Redcoats like never before, a fact recognized by both sides. Even French Foreign Minister Vergennes stated, “Eminent generals and statesmen…in every European court were impressed.” The loss of the capital was hard on the young nation, but, more importantly, Washington had once again held the army together in a lengthy and challenging campaign.

On December 19, 1777, General Washington moved his ragged army into winter quarters on some high ground about 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia called Valley Forge. While the British refreshed and retooled and stayed warm, the Americans shivered and starved, but heroically stayed together during the ensuing bitter cold months.

Next week, we will discuss the terrible winter at Valley Forge. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.