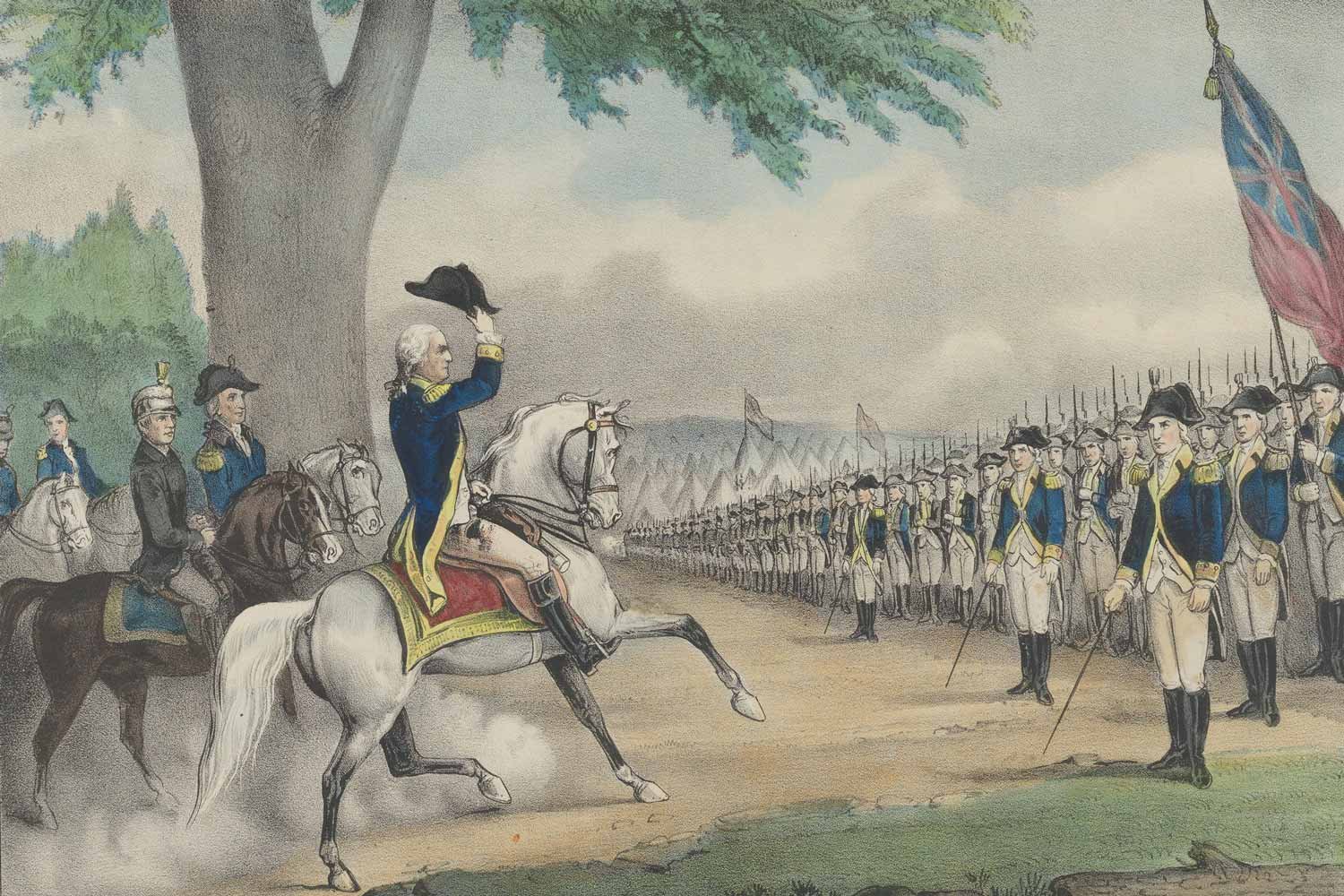

Washington Takes Command of the Continental Army

When it came to finding the right man to command the new Continental Army assembled around Boston, George Washington was the logical choice. John Adams quickly nominated Washington and Congress unanimously approved. As Adams stated, “This appointment will have a great effect in cementing and securing the Union of these colonies.”

To fully appreciate the task General Washington was given, it is important to understand the strength and capabilities of the two forces involved. Keep in mind that at the start of the American Revolution the Continental Army did not exist.

What we did have was a militia in every one of the thirteen colonies, all at various stages of development and all under their own leaders. The 16,000 relatively disorganized and under-equipped citizen-soldiers surrounding Boston were all militiamen. This was the force Congress “adopted” for its own in creating the Continental Army.

When Washington formally took command of the militiamen on July 3, 1775, he was unhappily surprised by what he saw. Instead of the virtuous, self-disciplined, and devoted patriot he had been led to believe comprised the new Continental Army, he found an untrained and unruly band from the four colonies east of the Hudson.

Most were in civilian dress and armed with family hunting muskets. Sanitation was deplorable and their latrines were insufficient or entirely lacking. Although General Washington and other leaders made camp sanitation a priority, their efforts were not very successful. In fact, for every soldier killed in combat, nine more died of disease, mostly due to poor sanitation.

The officers were not much of an improvement, as most had been elected because of their popularity with the men and not due to any military skills. As a result, training was non-existent, discipline was lax, and the men were disrespectful to their officers. More importantly, almost none of them had any real military experience.

That said, a few self-trained men became some of General Washington’s most trusted subordinates. Henry Knox was a twenty-five-year-old book seller when he first met Washington in the summer of 1775. By the end of the war, Knox would create and transform the Continental Army’s artillery arm into a formidable force, as capable as anything the British Army had to offer.

Nathanael Greene was a Quaker who was running his family-owned foundry in Rhode Island when hostilities broke out. Greene had no formal military training, but early in the war he completely reorganized the Quartermaster Corps allowing supplies to flow to Washington’s army. Later, he successfully led Continental forces in the Southern Campaign against Lord Charles Cornwallis and his British regulars.

Henry Alexander Ogden. “Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783.” Library of Congress.

Most men who served in the Continental Army were between the ages of 15 and 30 and they came from all walks of life. These men signed up to serve for one to three years and starting pay was about six dollars ($180 today) per month. If they got out of line or failed to comply with their orders, punishment was severe and included lashings and even death.

When in camp soldiers had one hot meal a day and received about a pound and a half of beef, a pound of bread, and two ounces of spirits (alcohol) each day, assuming Congress could keep them supplied. Unfortunately, Congress was completely dependent on the states for provisions and all too often, because of stingy and uncooperative state legislatures, the soldiers in the Continental Army were under fed.

When marching, the men carried about forty-five pounds of gear, everything from his weapon, ammunition, gun powder, mess kit (plate, knife, spoon, cup), knapsack, and maybe an extra blanket. On average, the soldiers marched about 15 miles a day.

Our Continental Army’s opponent was the British military, one of the most powerful in the world. The expeditionary force sent to America to quell the rebellion alone totaled 32,000 well-equipped and well-trained soldiers.

These units had more of everything than the Continentals; more uniforms, shoes, blankets, guns, bullets, gunpowder, cannons, horses, and so on. Moreover, it was commanded by seasoned, professional veterans who knew their business. Men who had engaged the French, Spanish, and Dutch on countless battlefields.

Adding to our challenges, the British Navy was the strongest in the world and controlled the seas. Their formidable armada could be used to both quickly transport troops from one location to another and to deny access to any vessels seeking to bring us supplies and other war materials. Additionally, while our army was terribly under-fed and under-clothed, British soldiers were kept well-supplied from England’s commissary.

Those were the odds stacked against General Washington as he rode north in June 1775 to take over the Continental Army surrounding Boston. While winning battles was critical to maintaining morale at home and with the troops, Washington knew his primary mission as Commander was to build and then preserve the Continental Army. He did this masterfully over the course of the next eight years and the end he achieved, America’s independence, was nothing short of miraculous.

Next week, we will discuss the rocky start for the Continental Army. Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.