The Start of George Washington’s Illustrious Military Career

With the demise of Lawrence Washington in 1752, George Washington inherited much of his half-brother’s property, becoming a significant landowner at the age of 20. Lawrence’s passing also opened up an Adjutant’s position in the Virginia militia that George coveted given his love of military history and desire to follow in his brother’s footsteps.

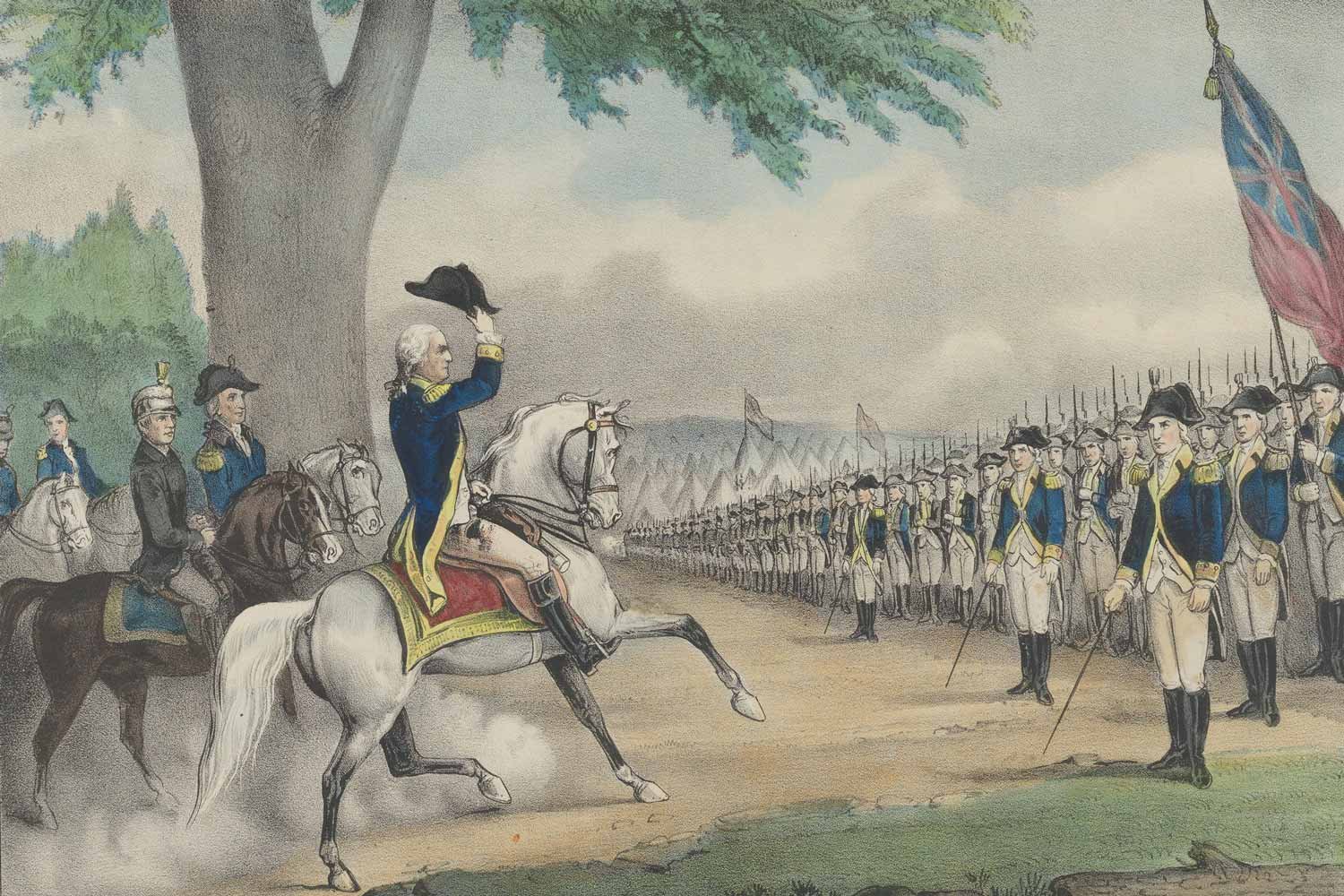

George had made his interest known and the Council of Virginia appointed him as Adjutant for the western region of the colony. On February 1, 1753, he took the oath of office and became Major George Washington, marking the start of his illustrious military career. In his new role, Washington commanded a portion of Virginia’s militia and was responsible for defending the frontier from Indian incursions.

About this time, England and France, two nations which had been European rivals for centuries, began to struggle for control of North America. While England had their thirteen colonies along the east coast, the French claimed Canada. Both nations had set up their colonies under a system known as mercantilism in which the colonies existed primarily to supply the mother country with raw materials and provide an outlet for its finished goods.

The main commodity in which France was interested was fur, found in plentiful supply in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the Ohio Valley. As English fur trappers and traders began to move into this area that France considered theirs, confrontations increased and tensions mounted.

In the fall of 1753, upon learning of a French presence in the Great Lakes region, Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent Washington to Fort LeBoeuf near Lake Erie to deliver an ultimatum for the French to leave. Washington completed this arduous round trip in 77 days. Although the French refused to comply, Washington gained a degree of fame from this exploit.

The following year, Washington, recently promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, was dispatched to this same area, but this time with two companies of militiamen from the Virginia Regiment. His assignment this time was to drive the French from the area, by force if necessary.

“Death of Jumonville” from J. T. Headley's The Illustrated Life of George Washington.

Once in the area, Washington learned a small detachment of French soldiers was nearby, led by Joseph Coulon, the Sieur de Jumonville, a French-Canadian army officer. Washington successfully attacked this unit on May 28, 1754, in a fight known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen. This incident, in which the entire French force was either captured or killed including Jumonville, ignited the French and Indian War.

Several weeks later, on July 3, the full French force, approximately 1,200 men arrived from Fort Duquesne. Washington, recently promoted to full Colonel, and his 400 militiamen made their stand inside an exposed, crude fort of wood palisades, in a field known as Great Meadows. Washington dubbed the structure Fort Necessity reflecting the precarious nature of the fort and location, and desperate cause for which they fought.

Shortly after dawn, a steady rain began to fall, and it kept up all day. Besides Washington’s men being completely exposed to the elements, most of the garrison’s powder got soaked. The French, mostly fighting “Indian style” and remaining hidden behind trees and rocks, initiated their attack around 11:00am.

At 8:00pm, the French offered to parley. By that point, about one third of Washington’s force was either dead or wounded, all his horses and cattle had been killed, and provisions for the remaining men consisted of two bags of flour and a little bacon. Washington, though terrible saddened, did the only reasonable thing he could do and surrendered to the French. Despite this apparent setback to his career, Washington’s star continued to rise.

The following spring, General Edward Braddock arrived with a force of about 1,300 regular British soldiers and marched back towards Fort Duquesne with Washington along in an unofficial capacity. Despite outnumbering the French by 4 to 1, Braddock’s force was soundly defeated, and Braddock was killed. Washington, displaying tremendous courage (he had two horses shot out from under him and he had four bullet holes in his clothing but was not injured), rallied the troops and prevented a complete rout.

Although George Washington continued to command the Virginia Regiment with great success until 1758, this battle largely ended Washington’s military career in the field until the onset of the American Revolution. Throughout this period, Washington displayed perseverance, coolness under fire, and courage that inspired those around him. These traits would manifest themselves again in Washington on a larger stage twenty years down the road.

Next week, we will discuss life at Mount Vernon. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In December 1777, following the loss of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital, General George Washington moved his Continental Army to Valley Forge for the winter. It would prove to be a desperately hard winter for the soldiers, with conditions that might have broken the spirit of less determined men, but one from which the American army emerged a more professional fighting force.