Henry Knox, “Noble” Hero of the American Revolution

Henry Knox is arguably the least known and most under-appreciated of our nation’s early military leaders. He was involved in practically every major battle in the northern campaigns of the American Revolution, and was instrumental in the creation of the United States Army after the War.

Born in Boston on July 25, 1750, Henry was the son of William and Mary Knox, emigrants from Derry, Ireland. The senior Knox was a modestly successful shipbuilder until Parliament passed the Currency Act and the colonies slipped into a depression, ruining Knox’s business. William abandoned the family when Henry was only nine years old and died three years later in the West Indies.

As a result, Henry quit the Boston Latin Grammar School he had been attending and took a job at a local bookstore to support his mother and three-year-old brother. Knox had a love for books and read all he could, especially on the great military heroes of the past. In 1771, just shy of his twenty first birthday, Henry opened his own shop called the London Book Store.

Henry, who had been a Boston street gang tough guy as a youth, was an imposing man at 6’ 2” tall and weighing well over 200 pounds. He was a witness to the Boston Massacre and testified at the trial of the soldiers. Later, perhaps influenced by that tragic event, Knox joined the rebellious Sons of Liberty, as well as an artillery outfit called the Train. He even formed a sister unit named the Boston Grenadier Corps.

At the age of twenty-three, he married the love of his life, Lucy Flucker, the pretty daughter of dedicated Loyalists. In fact, Lucy’s parents were among the Bostonians that sailed from the city when the British evacuated it on March 17, 1776. Not surprisingly, Henry was an unwelcomed addition to the family.

Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, Henry and Lucy left Boston, and Henry joined the militia besieging the city. His knowledge gained from years of studying military matters and experience with his colonial artillery unit was quickly put to good use. Knox was tasked with overseeing cannon emplacements and the construction of fortifications surrounding Boston.

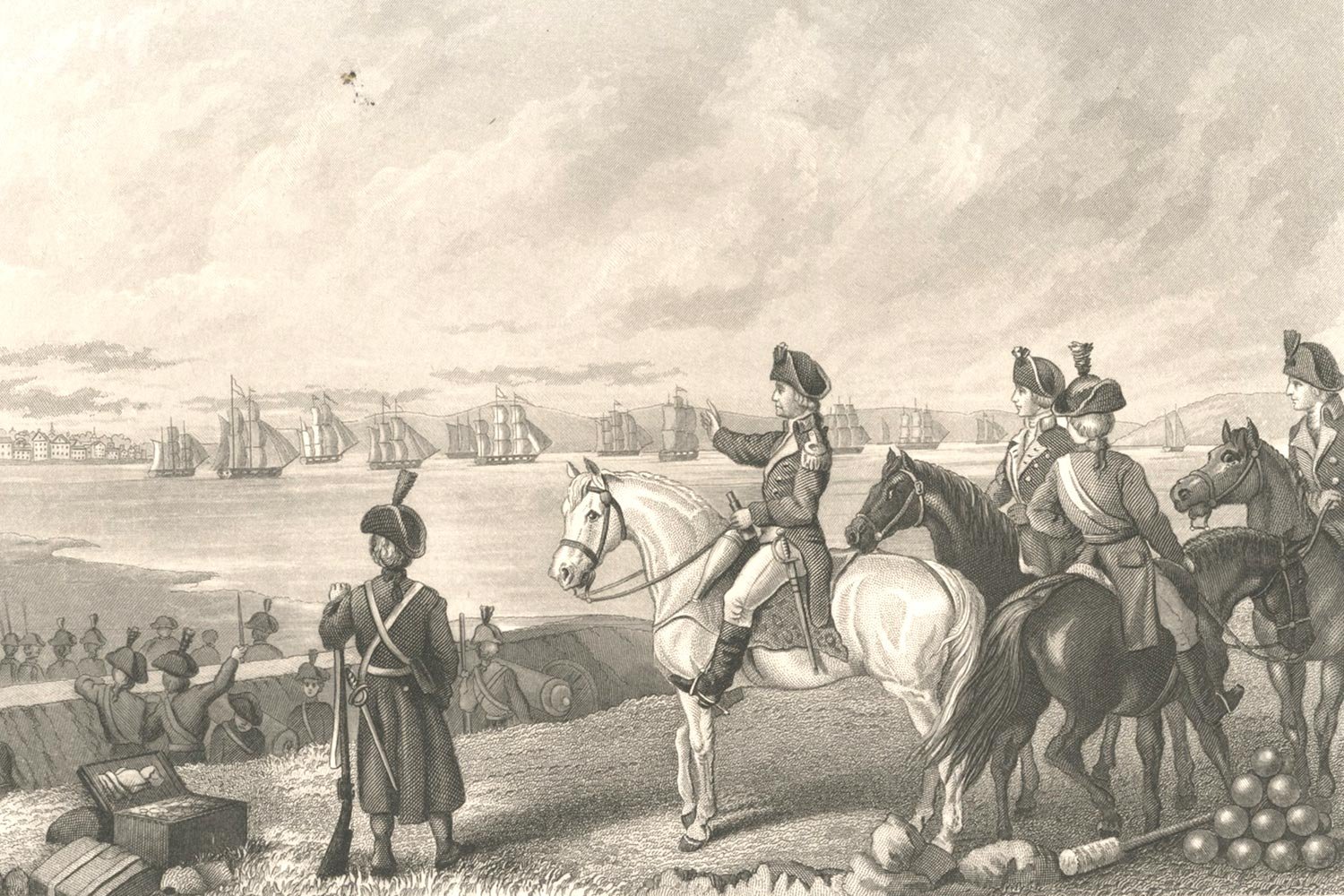

Currier & Ives. “Washington Taking Command of the American Army.” Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When General George Washington took command of the besieging force on July 3, 1775, he was impressed with Knox’s work, and the two immediately established a great relationship. Knox would prove to be Washington’s most constant companion and steadfast commander throughout the long fight for America’s independence.

After organizing the various militias into the newly formed Continental Army, one of Washington’s primary tasks was to find a way to drive the British from Boston. Both Washington and Knox knew strategically placed long range artillery would do the trick. The perfect spot was the unoccupied high ground of Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston Harbor. The problem was Washington’s force did not have any long-range guns on hand.

However, Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, along with Benedict Arnold, had captured over two hundred cannons when they successfully attacked Fort Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775. Unfortunately, Ticonderoga was 300 miles away and the harsh New England winter had already set in.

Not one to be discouraged, Knox suggested to Washington that he be allowed to try and bring some of the long-range guns to Boston on sleds. The Commander agreed and Knox headed north to begin his grand adventure. By December 6, 1775, the procession, described by Knox as a “noble train of artillery,” was on its way to Boston.

Henry Knox bringing artillery to end the siege of Boston.

Knox, who had recently been appointed a Colonel by the Continental Congress, selected fifty-nine pieces of artillery with a total weight of about 120,000 pounds. Keep in mind this was 1770s America. The roads were terrible, it was the dead of winter, and everything heavy had to be moved by teams of oxen.

Nevertheless, Knox and his intrepid men took the desperately needed guns across several rivers including the Hudson and the Connecticut, over and across the Berkshire Mountains, and on into Boston. This hardy band delivered the cannon caravan to General Washington on January 27, 1776, fifty-three days after setting out.

It was one of the greatest logistical feats of the American Revolution, and its leader, Henry Knox, was a 25-year-old bookseller with a third-grade education and no formal military training. Pretty amazing.

Next week, we will talk about how General Henry Knox served his country during the American Revolution. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

We take civilian control of the military for granted today in America. However, were it not for General George Washington’s actions and words in the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, things might be quite a bit different.