Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 1: The Search for the Northwest Passage

The dream of finding an all water route across North America, the mythical Northwest Passage, had been imagined since the time of Christopher Columbus. Incredibly, three hundred years after the Admiral of the Ocean Seas completed his epic voyages, the vast interior of the continent was still essentially unknown to Europeans. This great uncertainty led to numerous theories about what lay beyond what men could see.

One early misconception was that there was a mountain to the west from which all major rivers flowed, the Mississippi was the southern branch and the St. Lawrence the eastern, while their northern sibling might be the Mackenzie, with the second largest watershed in North America (after the Mississippi). But the River of the West remained the elusive piece of the theoretical puzzle. It was imagined by others that the Missouri, which enters the Mississippi just north of St. Louis, could be followed to within a short portage of the River of the West. The immensity of the Rockies and the difficulty in crossing them to get to the western watershed was not even vaguely imagined by men who dreamed of conquering the west, including visionaries like Thomas Jefferson.

As early as 1783, Jefferson had wanted to send an expedition to explore and chart the great unknown west of the Mississippi. He broached the subject with George Rogers Clark, the conqueror of the Northwest Territory, and tried to enlist him to lead the enterprise, but Clark declined. Three years later, Jefferson tried to send John Ledyard, an adventurous Connecticut Yankee, across Russia to North America’s Pacific Coast and then across the Rockies and Great Plains from the west. But Catherine the Great and her Siberian police put an end to the scheme, and there the matter rested for several years.

That changed in 1792 when Robert Gray, the captain of a merchant ship named the Columbia Rediviva, discovered the mouth of a great river he named after his ship. Gray had circumnavigated the globe between 1787 and 1790 trading furs from the Pacific Northwest with Cantonese merchants for tea and other Chinese goods and then transporting those goods to European and American markets. While on that voyage, Gray found a strong outflow at 46 degrees latitude but could not safely cross the sand barriers amid the swirling currents to enter the river. On the 1792 voyage, Gray managed to get into the river and spent several days exploring its lower reaches. With this discovery came an American claim on a portion of the Columbia watershed, an area that came to be known as the Oregon Territory.

“Robert Gray.” Wikimedia.

Gary’s findings reignited Jefferson’s interest in discovering a route to the Pacific Northwest and, as a representative of the American Philosophical Society, Jefferson commissioned a Frenchman named Andre Michaux to explore the upper reaches of the Missouri River and the lands that lay beyond. Michaux headed west from Philadelphia in July 1793 with detailed instructions from Jefferson, but Michaux turned out to be a French secret agent with his own agenda. Instead of exploring the west, Michaux tried to rally support for Revolutionary France among Kentuckians and recruit them for an invasion of Spanish Louisiana. Michaux’s efforts came to nothing, and he soon returned to France; but once again, Jefferson’s dream languished for several years.

Then, in 1801, a book entitled, Voyages from Montreal Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, was published in London. It detailed the explorations of a Scotsman named Alexander Mackenzie that sent waves of worry to those with dreams of an American empire stretching from sea to shining sea. Mackenzie was an explorer working for the North West Company, a rival of the Hudson Bay Company in the lucrative North American fur trade. Mackenzie had set out in 1789 to find an all water route across Canada to the Pacific but instead discovered the Mackenzie River and followed its course to the Arctic Ocean. Four years later, Mackenzie completed his journey across the continent when he journeyed down the Bella Coola River and reached the Pacific Ocean in July 1793, thus becoming the first European since Cabeza de Vaca, in 1536, to cross the continent north of Mexico. It was an incredible journey, but a commercial disappointment in that Mackenzie’s route did not establish the long-sought navigable all-water route to the Pacific.

Upon learning of Gray’s discovery of the Columbia River, Mackenzie renewed his push to connect North West Company land trade routes to the Pacific. But his efforts were thwarted by management who did not share his vision, and he returned to England. Mackenzie began advocating for the British to secure the Pacific Northwest before the Americans did and proposed that Great Britain build a series of forts far enough south, possibly to 45 degrees, to place the Columbia River well within British domains. Mackenzie concluded Voyages with an ominous note for American commercial interests, “But whatever course may be taken from the Atlantic, the Columbia is a line of communication from the Pacific Ocean. By opening this intercourse between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the entire command of the fur trade of North America might be obtained.”

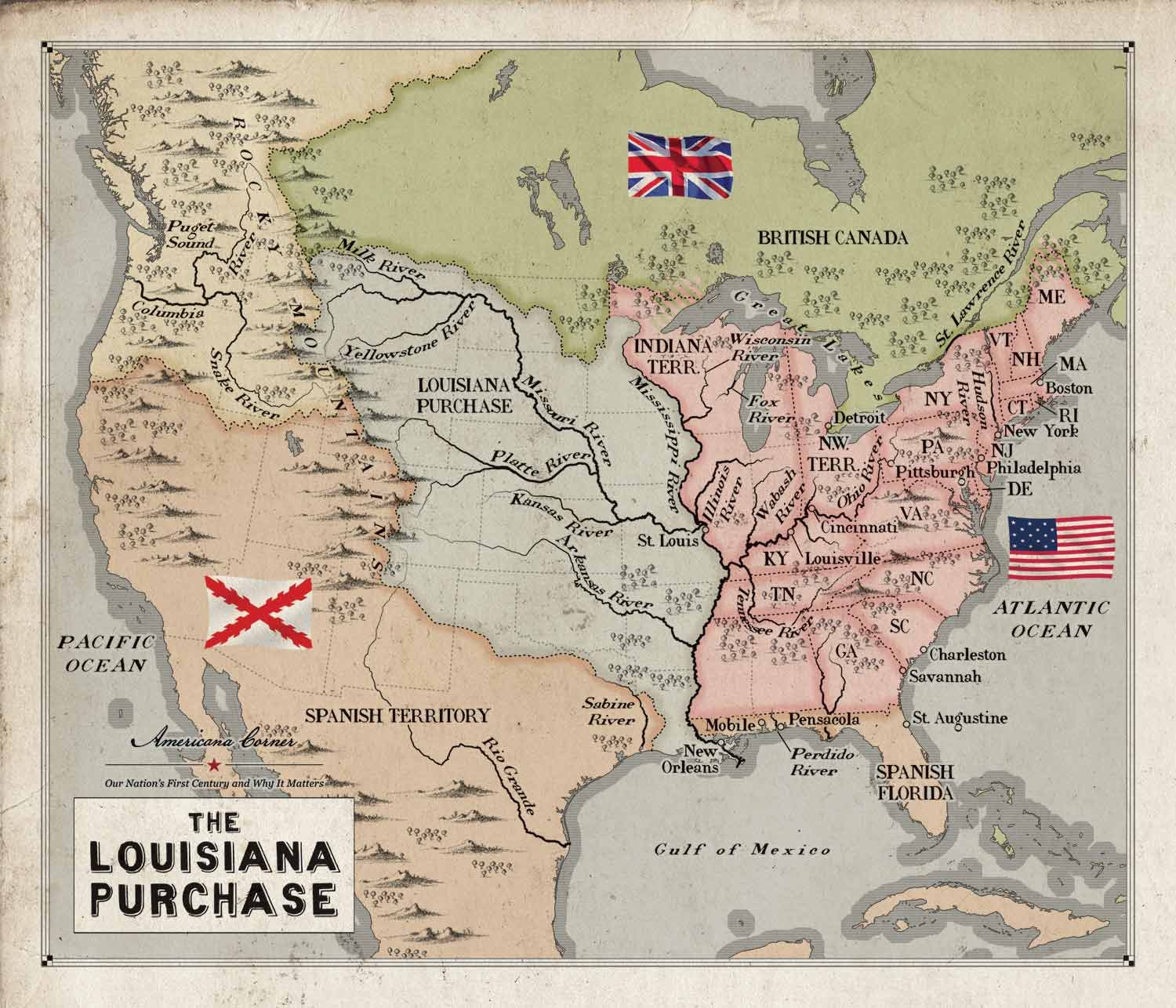

In 1802, Jefferson, now the president, read Mackenzie’s book and regarded his words as a “shot across the bow” and knew the race was on to establish an American claim to the Columbia basin and create a viable commercial route to Pacific. Accordingly, Jefferson asked Congress to appropriate $2,500 for an expedition from the Mississippi up the Missouri and then “possibly a short portage to the Western ocean… for the purpose of extending the external commerce of the United States.” Congress granted the money on February 28, 1803, but there remained one big problem – the land over which the expedition would travel was foreign territory, Spanish Louisiana. Jefferson began to correspond with Spanish officials to obtain their permission for the enterprise, but the Spanish were skeptical of Jefferson’s claims that the expedition was purely for scientific purposes. Fortunately for Jefferson and the country, that obstacle was removed when Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States later that year. The official transfer took place in New Orleans on December 20, 1803, and Jefferson’s dream was one step closer to reality.

Next week, we will discuss Thomas Jefferson’s western vision. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The dream of finding an all water route across North America, the mythical Northwest Passage, had been imagined since the time of Christopher Columbus. Incredibly, three hundred years after the Admiral of the Ocean Seas completed his epic voyages, the vast interior of the continent was still essentially unknown to Europeans. This great uncertainty led to numerous theories about what lay beyond what men could see.