British Forces Establish Foothold in Penobscot Bay

The greatest naval disaster in our nation’s history until Pearl Harbor was a largely forgotten episode that took place on the remote coast of Maine in the summer of 1779. The location was Penobscot Bay and the event proved to be an embarrassment caused by ineptitude, cowardice, and lost opportunities.

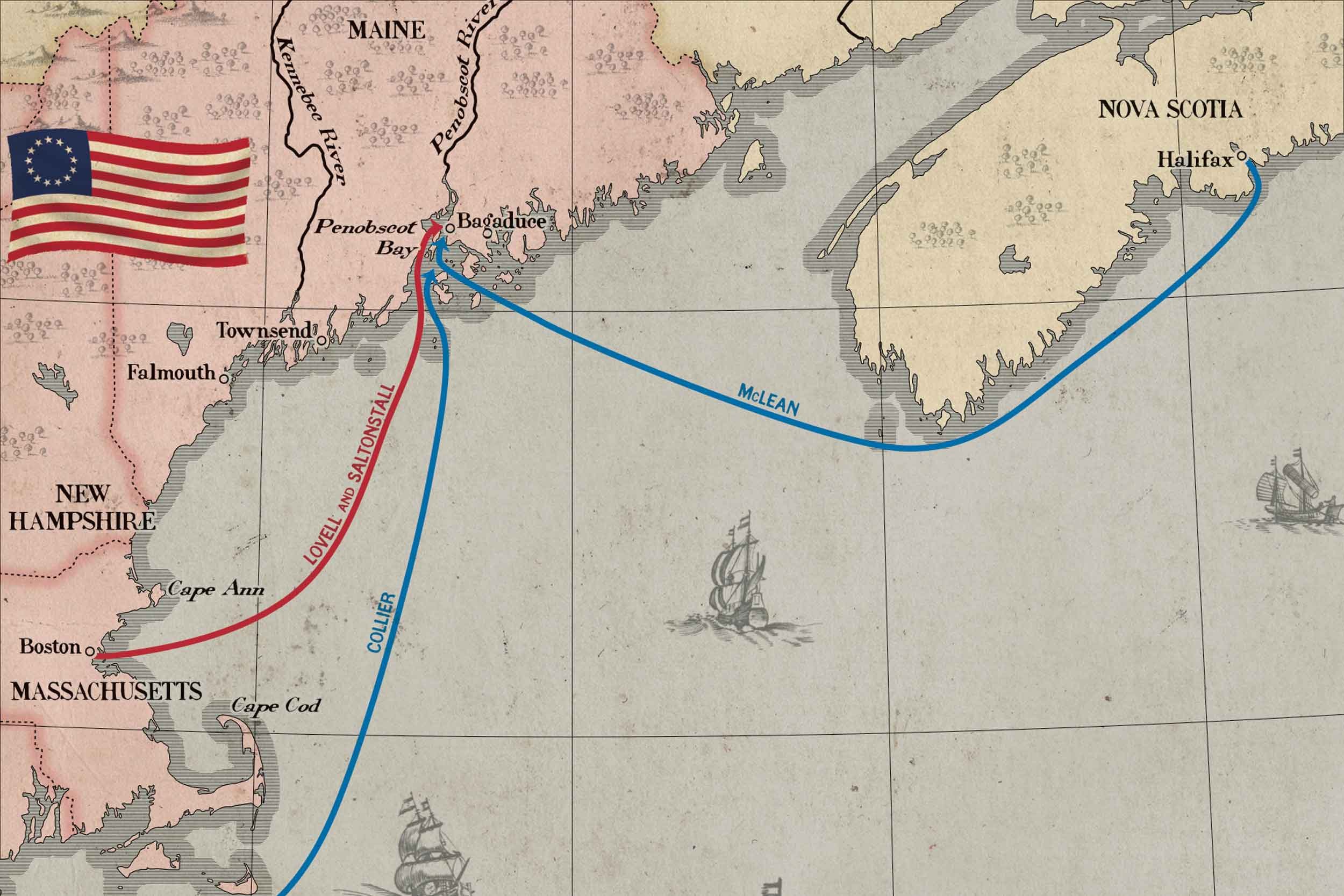

By the spring of 1779, the British had been fighting their rebellious American colonists for four years with little to show for their effort. Lord George Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, had shifted the British war effort to the south, but he also hoped to establish a northern foothold on the coastline between Boston and Halifax, Nova Scotia.

To that end, Germain directed Sir Henry Clinton, the Commander of British forces in North America, to send a contingent to Penobscot Bay, one of the best natural anchorages on the Atlantic seaboard and establish “a province between the Penobscot and St. Croix rivers.”

This new province, which was rich in timber for ship masts, was to be called New Ireland and populated with displaced Loyalists who would provide a buffer between the colonies and Canada. The deep harbor would also provide a haven for British warships closer to Boston and better allow their revenue cutters to suppress smuggling which was rampant in New England.

Clinton assigned the task to Brigadier General Francis McLean, a tough 62-year old Scotsman who had fought in nineteen battles during his time in the British Army and was admired throughout the service. McLean was given command of 700 men, 50 English artillerymen and the rest fellow Scotsmen, the Argyll Highlanders and a regiment of Lowland Scots known as the Hamilton’s after their founder, the Duke of Hamilton.

His companion in arms for this expedition was the naval commander, Captain Henry Mowat, also a Scot, who had spent considerable time cruising the eastern seaboard chasing smugglers and enforcing revenue laws. The command Mowat led was relatively small and included just three sloops of war (Albany, North, and Nautilus) and four transport ships. A capable sailor, Mowat was best known in New England and throughout the colonies for all the wrong reasons.

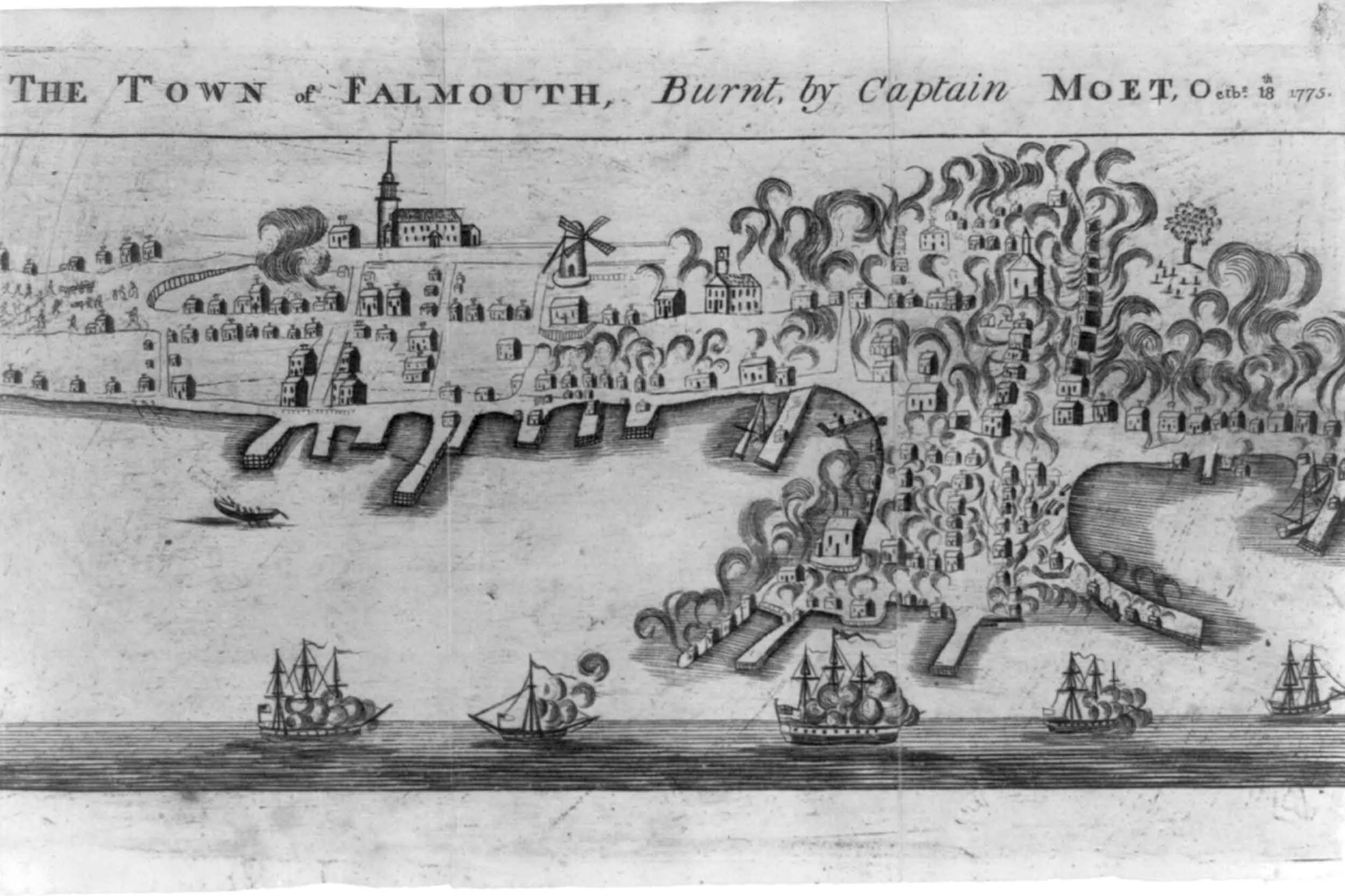

“The town of Falmouth, burnt, by Captain Moet, Octbr. 18th 1775.” Library of Congress.

In late 1775, to punish the colonies and thwart the burgeoning rebellion, Mowat was directed by Vice Admiral Samuel Graves to “lay waste, burn and destroy such Sea Port towns as are accessible to His Majesty’s ships.” Accordingly, on October 18, 1775, in retaliation for Falmouth (present day Portland), Maine supporting the rebel cause, Mowat’s ships, after giving notice for all citizens to evacuate, destroyed over 400 homes and warehouses, not discriminating between Tory and Rebel and not sparing women and children.

With the fierce northern winter close behind, the timing could not have been worse, and the suffering was terrible with over 1,000 people left homeless. The event was denounced on both sides of the Atlantic and, although four years had passed and despite the fact the captain had been following his orders, Mowat was still detested throughout the region.

The convoy arrived in Penobscot Bay on June 12, 1779, and McLean identified a prominent plateau, the Bagaduce Peninsula, on which to erect a fort, one he named Fort George after his sovereign. The site was well chosen as the plateau rose some 200 feet above the bay, with steep cliffs rising from Dyce’s Head, the beach from which the inevitable attack must come.

Within days, the troops and all supplies were landed and hauled up the slope, and the work began on the fort. Knowing word of the invasion would soon get back to Boston and a relief force sent north to expel them, McLean and his men worked around the clock to erect a barricade from which they could mount an adequate defense. Time was not on their side and, as it turned out, when the Americans finally did arrive the fort was far from finished.

A messenger bearing the startling news of the unwanted British visitors in Penobscot Bay arrived in Boston, about 240 miles away, on June 18, initiating a flurry of activity. Pulling together a contingent of men and supplies suitable for the occasion required significant logistical support, and this at a time when resources throughout the colonies had been strained from four years of fighting. Incredibly, Massachusetts managed to gather nine tons of flour and ten each of rice and salted beef, as well as twelve hundred gallons of molasses. Provisions also included twelve hundred gallons of rum, deemed a necessity for armies in the 1700s.

Within forty-eight hours, commanders were assigned and orders sent out for the militia to assemble and prepare to sail north. Interestingly, the Massachusetts General Assembly decided to ask neither the Continental Congress nor the Continental Army for assistance, wanting to make this a “Massachusetts only” show. As events were to prove out, not using Continental professional soldiers and experienced commanders would be the mission’s undoing.

Next week, we will discuss the opening assault on Penobscot Bay. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.