The Penobscot Expedition

In June 1779, with the British establishing a foothold in Penobscot Bay 240 miles northeast of Boston, the Massachusetts General Assembly sprang into action. The men chosen by the Assembly to lead the expedition to oust the Brits was an interesting group, all New Englanders and not a professional soldier among them.

The commander of the land force was Brigadier General Solomon Lovell, a farmer, state legislator, and justice of the peace from Weymouth who had one month of field experience commanding men. One of the young drummers under his command later wrote Lovell “made a much more respectable appearance in the deacon’s seat of a country church than at the head of an American army.”

The naval commander was Commodore Dudley Saltonstall, a hot-tempered former merchant ship captain from New London, Connecticut. Saltonstall owed his Continental navy commission to his brother-in-law, Silas Deane, a prominent member of the Continental Congress. Although the Massachusetts Assembly did not necessarily want Saltonstall to command the flotilla they were organizing, he refused to allow his three warships sitting in Boston Harbor to join the effort unless he was named commander.

After countless delays, the expedition finally set sail from Boston Harbor the morning of July 19, twenty-six days after learning of the British presence in Penobscot Bay. Although the delay in departing was unfortunate, the force that the Massachusetts Assembly finally pulled together was formidable, at least on paper. There were roughly 1,000 militiamen, mostly from the counties of northern Maine, a contingent of 200 Marines, and 100 artillerymen.

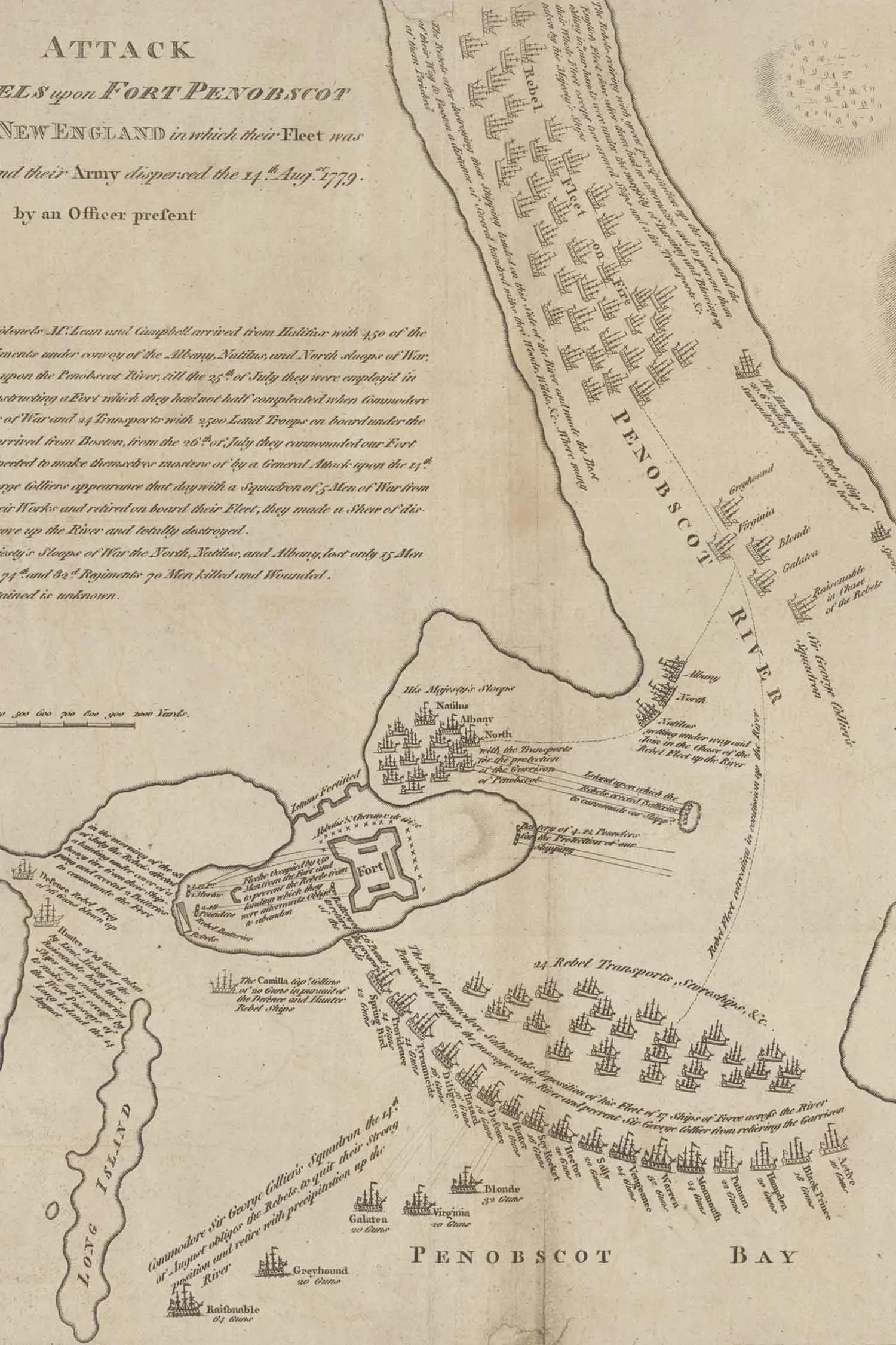

The troops were loaded onto twenty-five troop transports which were defended by nineteen warships, including Saltonstall’s flagship, the 32-gun frigate Warren. The combined fleet possessed 350 cannon and was the largest ever assembled by the Americans during the war. The Achilles heel of the American force would prove to be its lack of trained Continental soldiers and its inexperienced and uncooperative leadership group.

The fleet arrived off Penobscot Bay on July 25, almost six weeks after British General Francis McLean and his 700-man contingent of Scottish troops began construction on Fort George. In that time, they had strained mightily to erect a strong post, but the walls remained only a five-foot-tall earthen rampart with corner bastions for the few artillery pieces they possessed.

For the British Navy, Captain Henry Mowat had arranged his three warships in a strong formation between the Bagaduce Peninsula and Nautilus Island that allowed him to rake ships entering the Bay with broadsides, negating much of the numerical superiority of the American ships. But the fact remained that his small fleet was out gunned by the American ships 350 cannons to 58.

“Attack of the rebels upon Fort Penobscot.” New York Public Library.

In late afternoon, Lovell ordered an assault on the landing beach supported by Saltonstall’s warships but because of rough seas and the devastating fire from Mowat’s small fleet, the effort was called off. Two days later, the Americans captured Nautilus Island in preparation for another try at the well-defended beaches and then an attack on Fort George.

At 4 a.m. on July 28, the American ships Hunter and Sky Rocket, anchored just off shore, commenced a point-blank barrage at McLean’s 150 men defending the beach. The noise was deafening as solid balls and grapeshot forced the Argyll Highlanders to find any shelter they could from the storm. After thirty minutes of intense fire, the landing party led by General Peleg Wadsworth, a teacher from Plymouth, and consisting of 200 Marines and 500 Maine militiamen, left the transports and headed for the beach.

Between the horrendous artillery barrage and the sheer number of men rowing their way, the Scotsmen gradually retreated up the slope to the plateau and the relative safety of Fort George. The slope the Americans had to climb was precipitous, with a forty-five-degree angle and the ground wet with dew. To make the assent, the Marines needed both hands to pull themselves up using any bush or shrub they could grasp. With their muskets slung over their shoulders, they had no defense from the fire of the Redcoats holding the plateau and many became easy targets.

By 7 a.m., the Americans reached the edge of the woods at the top of the plateau, a few hundred yards from Fort George. Amazingly, in the span of two hours. these farmers from northern Maine, by grit and determination, had ascended a 200-foot-high slope in the face of fire from professional soldiers and now stood poised to capture the British garrison.

As General McLean watched the Americans across the clearing, he prepared to surrender the fort, standing next to the flagpole with his hand on the halyards. In his words, “I was in no situation to defend myself. I only meant to give them one or two guns, so as not to be called a coward, and then to have struck my colors.” But, to his astonishment, the Americans never moved from the woods.

With victory in their grasp and needing only a heroic charge and a man to lead it, General Lovell grew cautious and ordered his men to dig in and prepare to lay siege to Fort George. Having seen over one hundred of his men become casualties in the assault up the steep slopes of Dyce’s Head, Lovell, this farmer turned field commander, was not mentally prepared to send his men against the walls of Fort George. Unfortunately, Lovell would learn the hard way that “Fortune favors the Bold.”

Next week, we will discuss the failed opportunities at Penobscot Bay. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.