British Strike Back Against Clark’s Gains in Illinois Country

George Rogers Clark returned to Kentucky in February 1781 with visions of finally capturing the northern British bastion of Fort Detroit. However, although armed with a mandate from the Virginia legislature to raise an army and move on Detroit, very few Virginians were interested in participating in a campaign north of the Ohio when the British were in their backyard in the Tidewater region.

Despite recruiting challenges, Clark hoped to start from Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio in mid-June with 1,000 men. However, by the end of July, Clark had less than 400 on the rolls and he made the painful decision to call off the invasion.

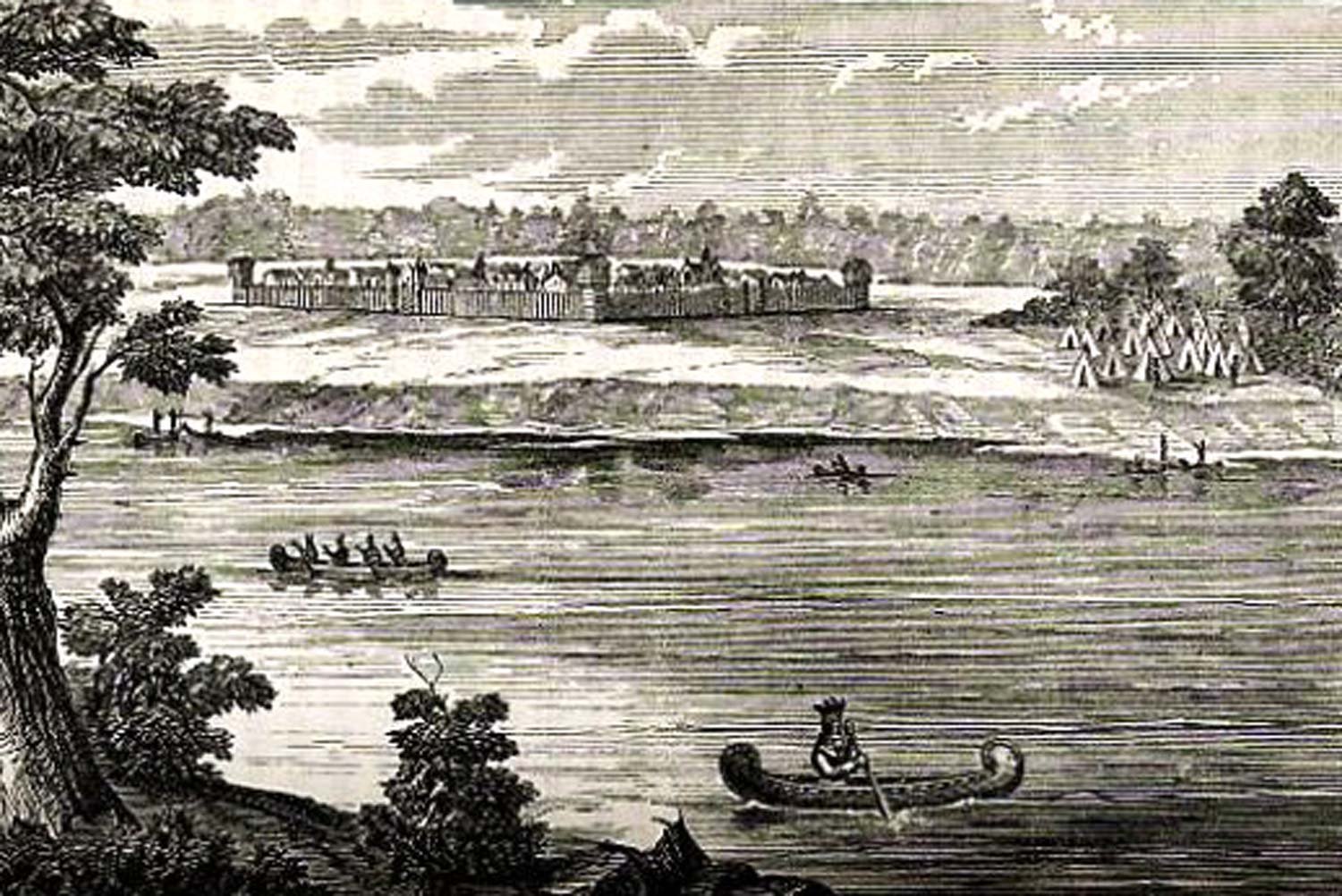

It was also proving more difficult to maintain and administer the territory Clark had captured than the actual taking of it. The Frenchmen in the Illinois Country who welcomed the Americans as they drove out the British, their eternal enemies, turned out to not be overly fond of American rulers either.

Additionally, the men Clark left behind to garrison the posts grew increasingly tired of no pay, little food, and the boredom of a frontier fort. The state of Virginia, bereft of money, provided little help and Clark felt isolated and forgotten by the government in Richmond.

Unbeknownst to Clark, his unbroken string of successes had greatly annoyed British officials back east and Sir Henry Clinton, commander of British forces in North America, and Frederick Haldimand, the Governor of the Province of Quebec, wanted Clark dealt with once and for all. Haldimand called on Joseph Brant, the most successful partisan fighter on either side during the war, to take a force to the Falls of the Ohio and destroy Clark.

Brant was a talented Mohawk Indian from New York who had wreaked havoc on Patriots from the Mohawk River Valley to the upper Susquehanna since the early days of the American Revolution. Haldimand was hoping Brant could replicate his brand of terror in Kentucky, and Brant did that starting in mid-August 1781.

Brant raised a force which included several hundred Mohawk, Shawnee, and Delaware warriors, and British partisans under Alexander McKee and George Girty, one of the notorious Girty brothers. Their primary objective was to destroy Clark’s army when it was strung out on its march north.

The Indians following Brant had little desire to try their luck against Clark, the Chief of the Long Knives as he was called. When word through spies reached their camp at the mouth of the Miami River that Clark’s expedition to Detroit had been called off, that was all the excuse they needed to shift their focus away from Clark and look for easier targets.

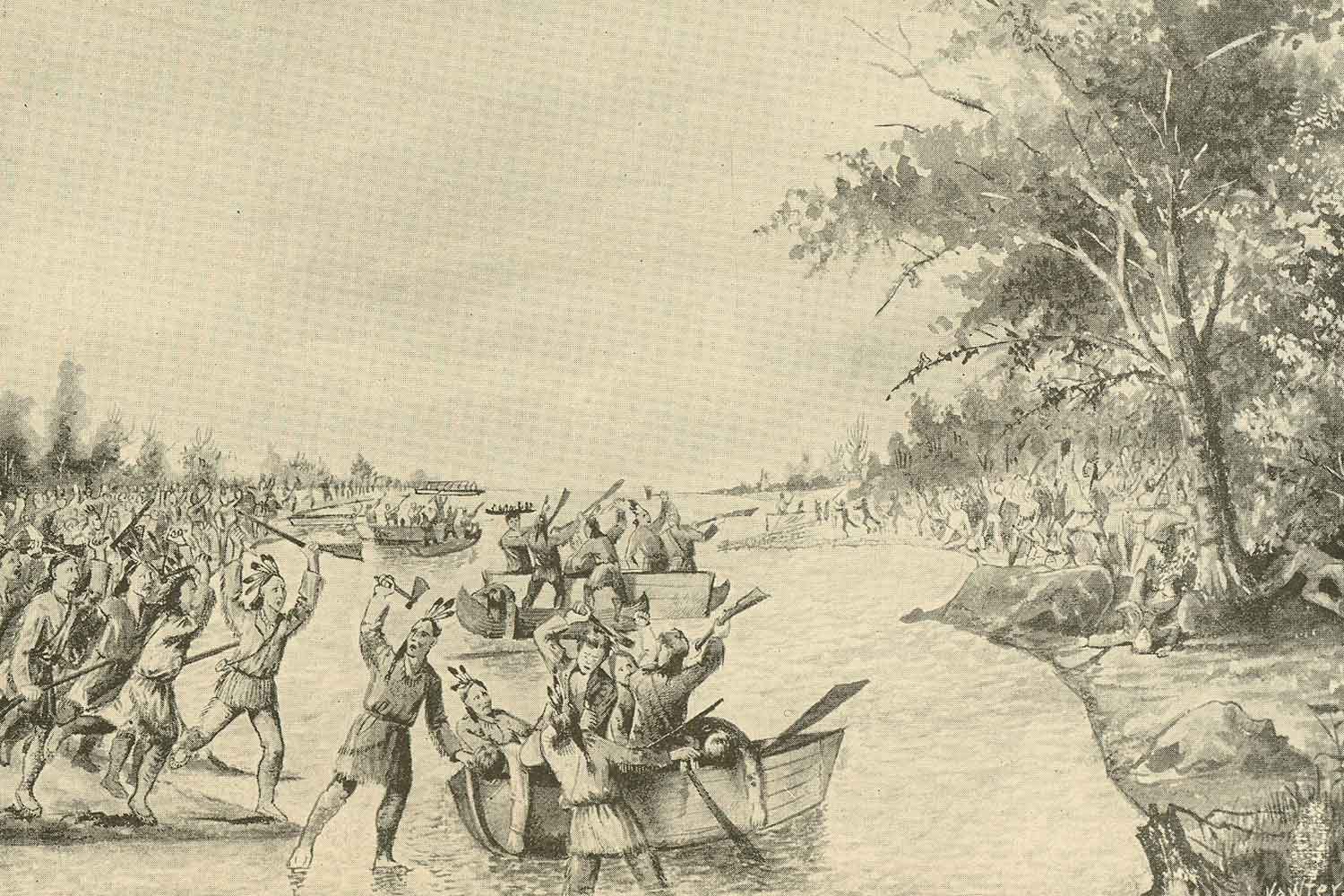

“Lochry’s Defeat from the Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio by William English, Vol. 2.” Wikimedia.

On the morning of August 24th, Brant ambushed a unit of 100 men led by Colonel Archibald Lochry enroute to reinforce Clark at Fort Nelson. Astonishingly, Brant killed or captured the entire force without incurring even one casualty; Colonel Lochry was among those killed. Brant and his war party soon moved onto the settlements and murdered and pillaged the Kentuckians as he had previously done to those in New York. Clark raced east from Fort Nelson with three hundred men, but the ever elusive Brant was on the trail heading north before Clark arrived.

Once again, Clark was absent from the scene when Indian raiders hit Kentucky, and the criticism began to mount despite Clark having valid reasons for his absences. Clark had been under orders constructing Fort Jefferson on the Mississippi when Captain Bird attacked in 1780 and at Fort Nelson preparing an invasion of British territory to crush the source of the Indian raids when Brant struck in 1781.

The criticism was that Clark, as commander of the Kentucky militia, was spending too much time conquering the west and not enough time defending the settlements under attack. It was argued, perhaps legitimately, that Clark should focus more on building forts along the Indians’ main avenues of approach into Kentucky such as the Licking River and Limestone Creek and less on dreams of conquest and capturing a fort 450 miles away.

Even those jealous of Clark’s successes admitted that just his presence closer to the settlements would deter Indian attacks. But Clark, ever the visionary, remained at Fort Nelson, refusing to surrender all he had fought for in the west, lands that he knew would be part of our country someday. It is also likely that Clark was too emotionally invested in the western lands and this closeness clouded his judgement.

There were also rumblings from Clark’s rivals of financial improprieties with some of the provisioning done by Clark and his subordinates while winning the west. Clark was a soldier, not a bookkeeper, and he secured what food and supplies he needed to keep his men alive and the army together. So certain was he in the correctness of his actions that Clark personally signed for many supplies, confident politicians back east would support him; his confidence in these officials would prove to be naive. Importantly, none of the rumors were ever substantiated, but they swirled nonetheless, and created a bitterness in Clark.

In any event, in late October, Kentuckians received the stunning news that Lord Charles Cornwallis had surrendered to General Washington at Yorktown. Hopes were raised that the bloodshed in Kentucky was near its end, but those dreams would soon vanish.

Next week, we will discuss Kentucky’s bloody year of 1782. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.