The Battle of Piqua

Kentucky had suffered greatly from Shawnee raids in June 1780 and Colonel George Rogers Clark decided it was time to take the fight into their homeland. His invasion across the Ohio would lead to the largest battle west of the Appalachians during the American Revolution.

After burning the Shawnee village of Chillicothe, Clark and his army of 1,000 angry Kentucky militiamen moved onto Piqua, about twelve miles to the northwest. Piqua, set on a bluff overlooking the Mad River, was the main Shawnee village in the region, and held roughly 3,000 people. As with most Shawnee villages, it was surrounded by acre upon acre of fertile fields of corn.

It was here that several hundred Shawnee, led by Simon Girty, made their stand. Girty was a notorious guerilla fighter with the sort of background only found on the American frontier. In 1756, at the age of fifteen, Simon was taken captive by a raiding party of Ohio Senecas and spent the next seven years being raised by Guyasuta, the tribe’s chief. In 1764, Girty was returned to the British in a prisoner exchange at the end of Pontiac’s Rebellion, but Girty found he preferred the Indian way of life.

Girty fought alongside George Rogers Clark, Daniel Boone, and Daniel Morgan during Lord Dunmore’s War and initially joined the American cause at the outbreak of the American Revolution. However, in 1778, when expeditions were being planned to destroy Indian villages in the Ohio Country, Girty switched sides, and soon was leading attacks on Kentuckians with a vengeance.

As Clark and his army approached Piqua, Girty was anxious to test himself against the almost mythical Clark and prove to his Indian followers that he, Simon Girty, was the better fighter. He placed fifty Shawnee warriors in a blockhouse adjacent to the palisaded wall that surrounded Piqua and deployed the rest in the woods behind a breastwork of fallen logs.

“Map of Battle of Piqua.” National Park Service, Wikimedia.

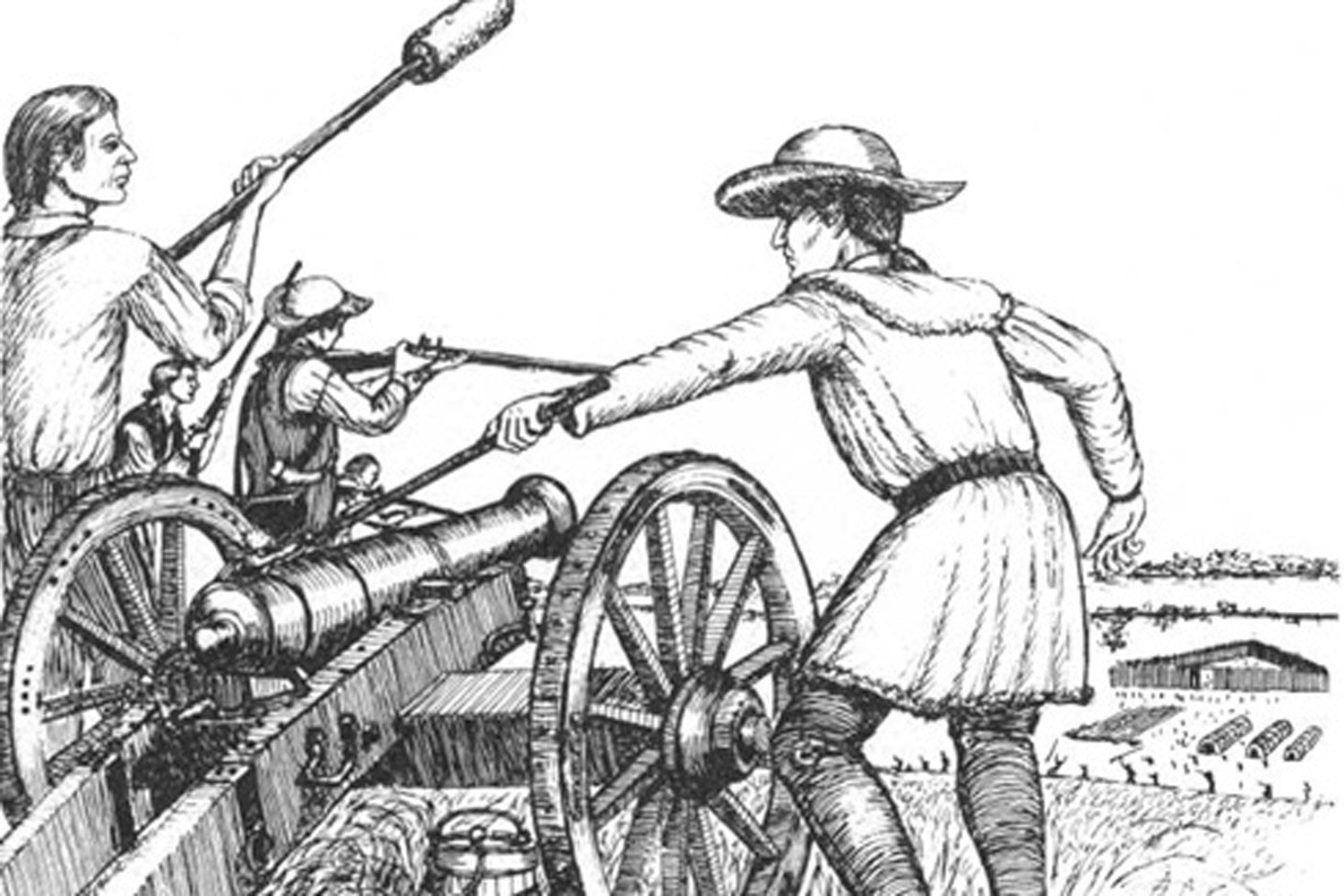

On August 8, Clark attacked the entrenched Indians who fought fiercely as men will when defending their homes. The Americans made little progress until Clark brought his cannons into play and blasted away at the blockhouse, the strong point of the Indian’s defenses. The Shawnee fled out the back door as cannon balls shattered the log walls of the front of the structure. The remaining warriors retreated out of rifle shot and conceded the town to the Americans, who proceeded to destroy everything of value at Piqua including all its houses and eight hundred acres of corn.

Although the Kentucky militiamen held the field, their victory had been costly with over thirty men killed and many more wounded. The Battle of Piqua would prove to be the largest engagement in terms of number of participants of any battle west of the Appalachians during the American Revolution. Despite losing over one hundred warriors and all their possessions, the Indians were not subdued. If anything, they were more enraged than ever and their bloody assaults on the Kentucky settlements would commence anew the following spring.

As 1781 opened, George Rogers Clark hoped that this would finally be the year when his dream of capturing the British stronghold of Fort Detroit would become a reality. Clark recognized perhaps clearer than anyone that this bastion of British power in the west must be destroyed or the Indian depredations on Kentucky would never cease.

The previous fall, Clark had returned to Richmond, the Virginia capital since April 1780, and persuaded Governor Thomas Jefferson to authorize and fund a force of 2,000 men under Clark’s command to invade British territory and take Detroit. However, as time would tell, authorizing a force of this size is not the same as finding the men to fill the ranks and the money to pay for the provisions.

As Clark began his journey back to Kentucky, the infamous American hero turned traitor, Benedict Arnold, now a British Brigadier General, and a flotilla with 750 veteran troops, swept up the James River and captured Richmond on January 4, 1781. Jefferson and the rest of the Virginia government fled west, and Arnold, after filling forty two boats with supplies and munitions, burned most of Richmond to the ground. After destroying warehouses and a cannon foundry at nearby Westham and a supply depot at Chesterfield, Arnold’s raiders returned to their ships in the James River.

Upon hearing the news, Clark turned around and headed back to Richmond where Governor Jefferson, who had returned to Richmond, gave Clark command of the city’s defenses. Arnold, learning that Jefferson was back in town, sent his formidable cavalry commander Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe, a Loyalist from New York, to capture the Governor.

Simcoe hustled his horsemen towards Richmond, expecting easy pickings, and unaware he was now dealing with George Rogers Clark. Using the ambush tactics that worked so well in the west, Clark deployed two hundred men in the woods along the main road into Richmond. He then sent forty mounted men forward to fire on the Brits and race to back towards town, hoping to draw Simcoe’s troops into his trap. The Brits took the bait and Clark’s men delivered a devastating volley, inflicting heavy casualties, sending Simcoe back where he started, and effectively ending Arnold’s raid.

Clark again turned towards his homeland of Kentucky where, unfortunately, more disappointments awaited him.

Next week, we will discuss the on-going struggles in Kentucky. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.