Kentucky Under Assault

With the capture of Fort Sackville, Kaskaskia, and Cahokia, Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark had gained control of the southwestern portion of the Province of Quebec, better known as the Illinois Country, for the United States. Clark was at the height of his popularity, but the ambitious twenty-six year old wanted more and turned his attention to the crown jewel of British possessions in that part of the world, Fort Detroit.

The full summer warring season was in front of him, and Clark felt Detroit could be his if he could quickly raise an adequate force and acquire the provisions necessary to sustain his army on the 450-mile march to reach the fort. But the year was 1779, and the young country and Virginia were broke and many Americans were tired from four years of fighting. As a result, Clark’s army was not formed, and Detroit remained in British hands. As Clark frustratingly wrote, “Detroit was lost for want of a few men.”

Kentuckians could certainly be excused for their reluctance to join Clark in this mission that would take them far from their homes and families when the Indian threat to Kentucky was still very real. While Clark had been on his heroic operation to the Illinois Country, the Indian onslaught on Kentucky had not slowed at all.

Since Blackfish, the great Shawnee chief based in Chillicothe on the west bank of the Scioto River, had attacked Logan’s Fort in late May 1777, the settlements of Kentucky seemingly had been under constant assault. In September 1778, Blackfish led another large contingent of warriors south into Kentucky, and this time the target was Boonesboro, established by the great American explorer Daniel Boone.

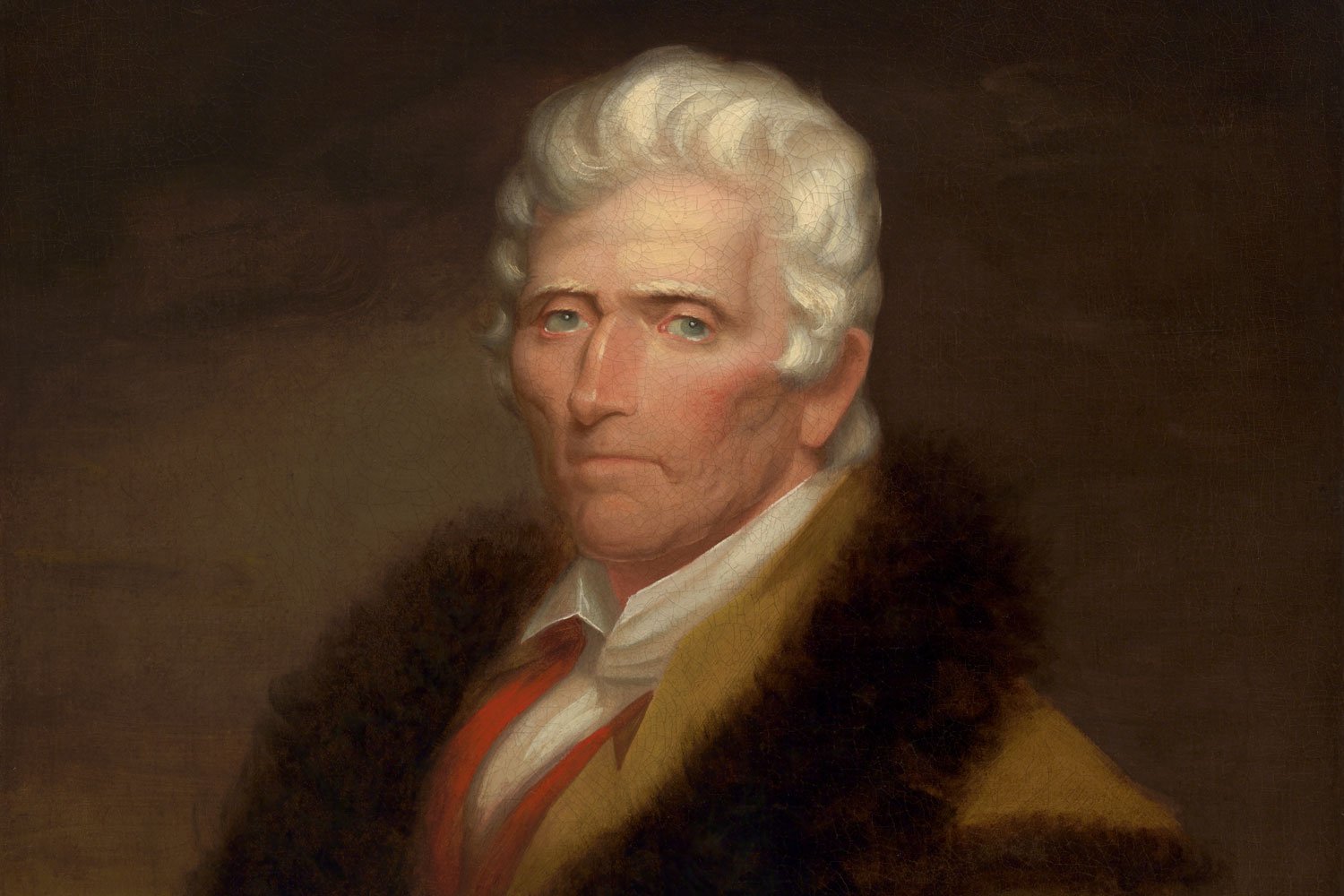

“Daniel Boone.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Boone and thirty others had been captured by Blackfish earlier in the year while collecting salt along the Licking River. Because of his fame, Boone, rather than being killed and scalped, was adopted by Blackfish into his family. When Boone learned of the intended raid on Boonesboro, he made his escape and raced 160 miles on foot in five days, staying just ahead of his pursuers, to forewarn the people.

Although the siege of Boonesboro would last from September 7-18, Boone’s efforts had saved the post and Blackfish was forced to retire back across the Ohio. Blackfish would be killed the following May while trying to defend Chillicothe when Captain John Bowman and Kentucky militiamen attacked the village and burned it to the ground.

In the spring of 1780, Thomas Jefferson, then Governor of Virginia, hoping to secure Clark’s western gains, sent Clark to the Mississippi to establish a post just south of its confluence with the Ohio. While Clark was busy building Fort Jefferson, the British launched a major offensive intended to recapture the Illinois Country from Clark, and the small Spanish village of St. Louis across the river.

Clark was at Fort Jefferson when he received word of an Indian raiding party moving towards Cahokia. He took a contingent and canoed upstream 100 miles, a grueling task against the Mississippi current. Clark reached Cahokia on May 25, one day before the Indians arrived before the fort. Clark quickly advanced from the fort with 100 men and a six-pound cannon and scattered their forces, the Indians having little stomach for facing Clark.

Less than two weeks later, another British force, much larger than the one sent against the western outposts, crossed the Ohio River into Kentucky. Led by Captain Henry Bird, it was the largest British and Indian force ever to invade Kentucky with 140 Redcoats, 30 militia and 800 native warriors.

The plan was to strike Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio (present day Louisville, KY) and then attack the settlements. But such was the fear and respect Clark inspired in both the Indians and British commanders that upon hearing a rumor that Clark was at the Falls (he wasn’t), Bird bypassed the fort and took his force straight to the settlements.

The British captured Ruddle’s Station on June 22 and then moved on to Martin’s Station which surrendered as well. Bird now had 350 captives from the two settlements to guard and feed, and this weighed upon his mind. But more worrisome to Bird and his men was they knew Clark would soon be coming their way and might possibly cut off their retreat to Detroit, turning the Brits from captors into captives. With his Indian allies leaving him in droves, Bird abandoned his mission and turned north, arriving in Detroit on August 4.

A message was sent to Fort Jefferson that he was needed back east, and the indefatigable Clark left for Harrodsburg, roughly 270 miles away, arriving just after the Brits had skedaddled. He may have missed Captain Bird, but he was not too late to exact some frontier vengeance on the Indians.

Quickly assembling 1,000 men and three cannons, Clark’s band crossed the Ohio on August 2, 1780, and headed north into Shawnee territory. The natives abandoned their recently rebuilt town of Chillicothe when the army approached, and the Kentuckians burned it to the ground and destroyed all their crops once again.

The next Indian town in their path was Piqua and it was here that several hundred Shawnee, led by Simon Girty, planned to make their stand.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Piqua. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace.