Creating America: The Treaty of Paris Delivers Favorable Terms

After Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington in Yorktown on October 19, 1781, word of the surrender was sent to England. When finally received by Lord Frederick North, the Prime Minister, he repeatedly exclaimed “Oh God! It is all over!”, and it was for all intents and purposes.

Simply put, the British decided the war was too costly to continue. Not only was the war in North America expensive to prosecute, but it was also a distraction from England’s defense of their more lucrative possessions elsewhere in the world such as the sugar islands in the Caribbean and trading posts in India.

Additionally, consider that America was 3,000 miles from Britain, but France and Spain were only across the English Channel and both had significant navies. Consequently, England decided the time had come to end the war.

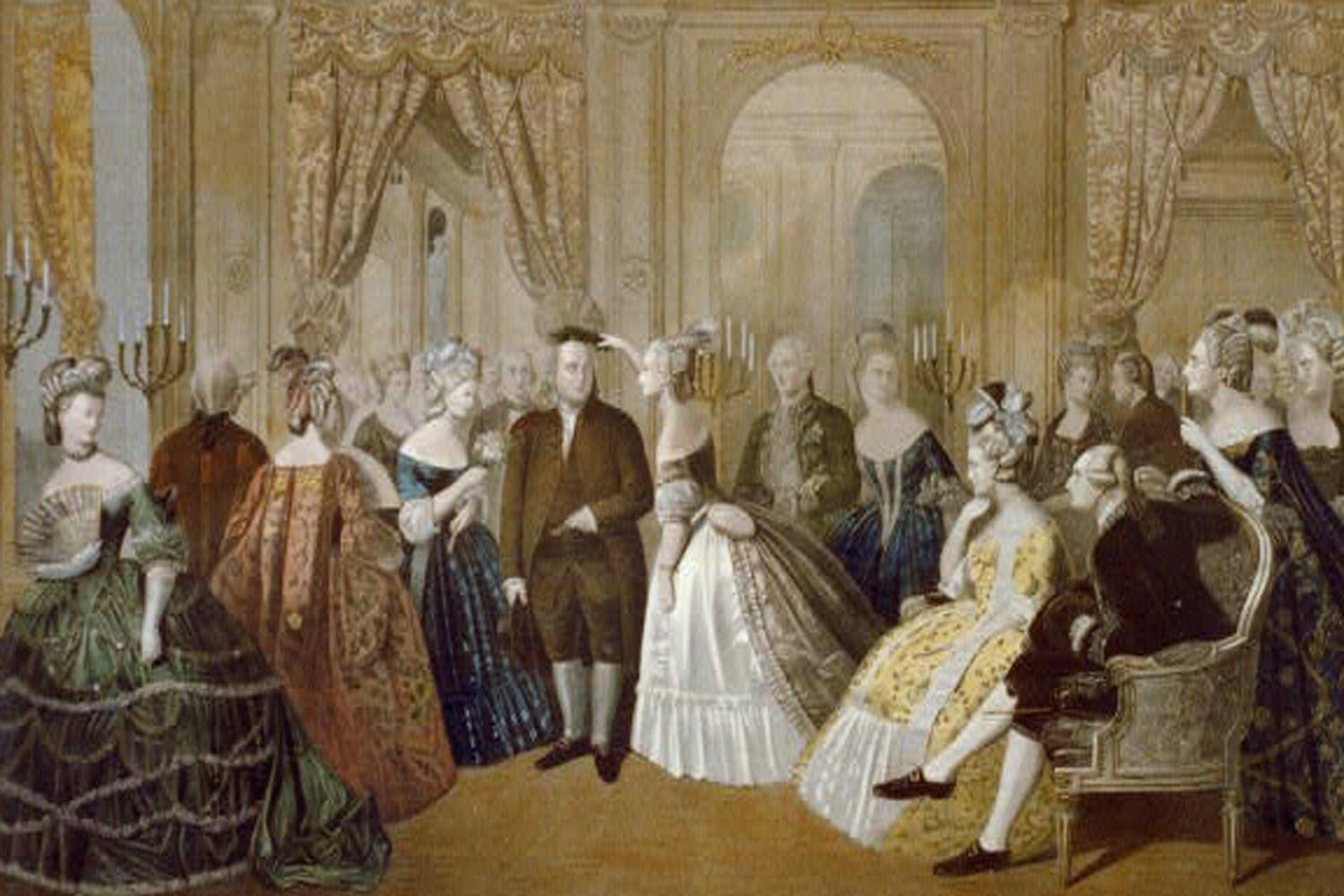

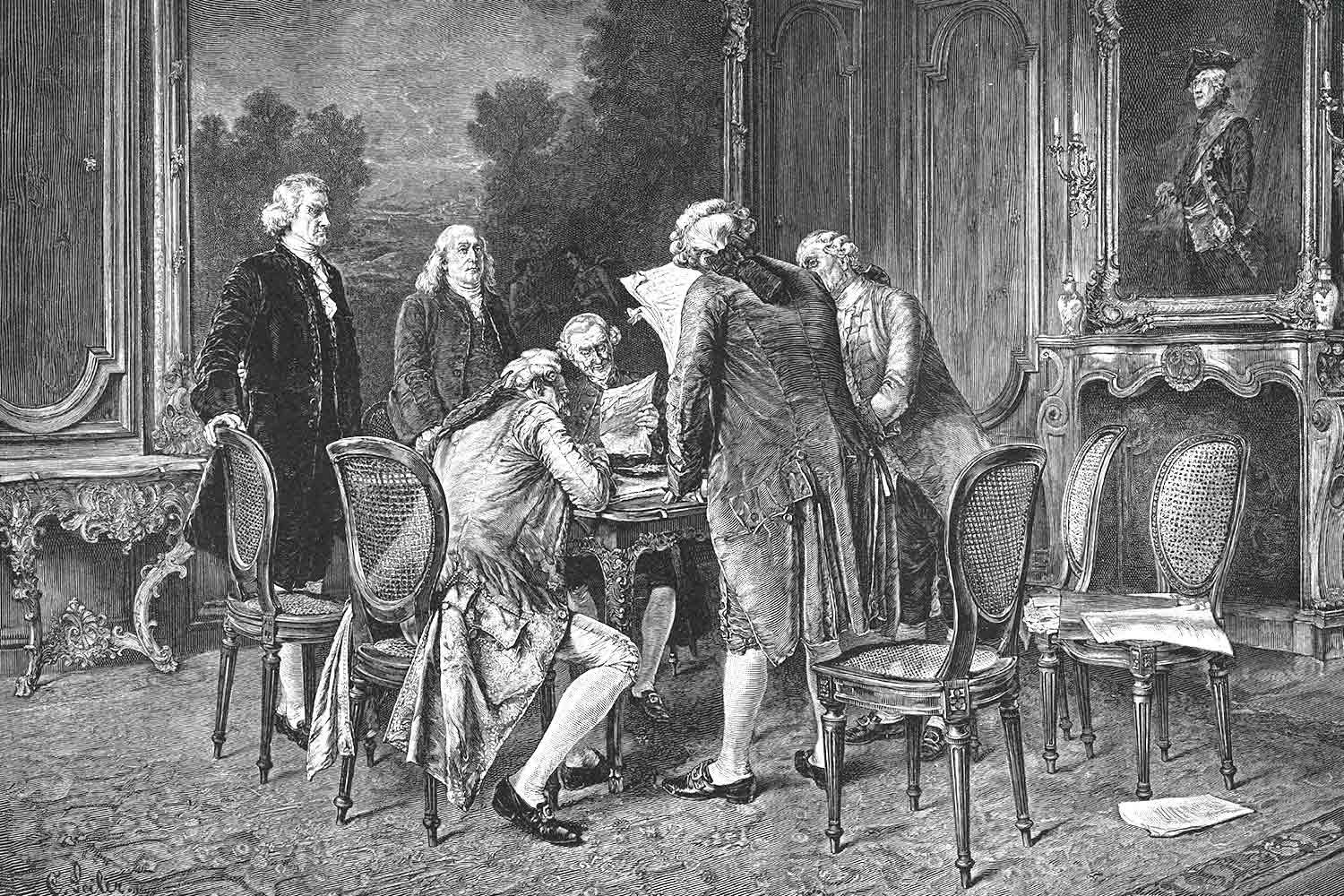

Peace negotiations commenced in Paris in April 1782. The United States contingent was a real powerhouse. It included Benjamin Franklin, one of the most recognized men in the world, John Jay, the future first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Henry Laurens, the ambassador to The Netherlands, and John Adams, our future President.

When discussions began, the British still held some significant possessions in America, namely Charleston and New York, as well as all of Canada and numerous western forts and trading posts. Additionally, since the Continental Army was not very active in 1782, the British were in no hurry to finalize the details of the treaty.

By September, no progress had been made regarding the final terms of the treaty. While France, England, The Netherlands, and America wanted peace, Spain insisted on continuing the war until they captured Gibraltar from the British.

At that point, France’s Foreign Minister Vergennes suggested that the America be granted independence, but its boundary be east of the Appalachian Mountains. Additionally, Britain would retain all land north of the Ohio River, while Spain would take possession of all lands south of it.

This ludicrous proposal would have left America a weak nation with no possibilities for expansion. Our negotiators must have wondered with friends like the French who needs enemies.

In any event, the Americans decided to open direct negotiations with England. The new British Prime Minister Lord Shelburne, who had replaced Lord North after the Yorktown debacle, was receptive to the idea. He reasoned that a strong America would be less dependent on France and had the potential to be a great trading partner. He was proven correct.

The terms Shelburne proposed granted the United States their independence, all lands east of the Mississippi and south of Canada, as well as fishing rights in the Canadian Atlantic. By all accounts, these terms were very generous.

There were also provisions that called for Loyalists to have their property returned to them and to allow British creditors to collect what they were owed by Americans. These last two stipulations would prove to be a source of friction in years to come.

On September 3, 1783, this treaty, as well as separate ones with France and Spain were signed in Paris. Collectively, these agreements were known as the Peace of Paris, and they ended this world-wide conflict.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why does it matter to us today that our team of negotiators obtained the favorable terms they did for America in the Treaty of Paris? First, imagine an America that ended on the eastern slopes of the Appalachians, with Canada extending to the Ohio and Spain occupying the area from there to the Gulf of Mexico. That is how America would have looked if France had gotten their way during the negotiations with Britain.

Our team of Adams, Franklin, Jay, and Laurens, by choosing to negotiate directly with England, secured terms that allowed for our great nation to expand to the west and fulfill our destiny. More importantly, we secured our independence from England, our ultimate goal in the long, bloody conflict just ended. All those lives lost, and all that treasure expended, somehow seemed justified by this providential ending. We were now a nation.

SUGGESTED READING

“The Treaty of Paris: The Precursor to a New Nation” by Edward Renehan was published in 2007. It is an interesting, easy-to-read account of the negotiations which resulted in our nation officially gaining its independence from England.

PLACES TO VISIT

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park is one of the most beautiful spots to visit in eastern America. Located where Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia meet, this pass was the main thoroughfare for pioneers from the Atlantic seaboard to the new lands west of the Appalachians granted to the United States by the Treaty of Paris.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

After Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington in Yorktown on October 19, 1781, English officials reached the painful conclusion that the war was simply too costly to continue. Not only was the war in North America expensive to prosecute, but it was also a distraction from England’s defense of their more lucrative possessions elsewhere in the world, such as the sugar islands in the Caribbean and trading posts in India.