John Adams Negotiates Peace with England

John Adams was solely responsible for opening a strong relationship with the Netherlands between 1780-1782. Besides concluding the Dutch-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce, Adams also secured a much-needed loan from Dutch bankers.

Within days of completing his work in Amsterdam, Adams received a summons from John Jay, another American diplomat in Paris, to immediately return to the French capital. Peace talks with the English were heating up and Jay wanted Adams’ assistance. Off he went to do what seemed impossible just a few years before, secure our independence from Great Britain.

Once in Paris, Jay briefed Adams that the French, especially the Comte de Vergennes, the French Foreign Minister, were not showing any sense of urgency in the negotiations. Moreover, they did not seem inclined to demand very much from the British for the Americans. It seemed France wanted us to be independent but not too independent.

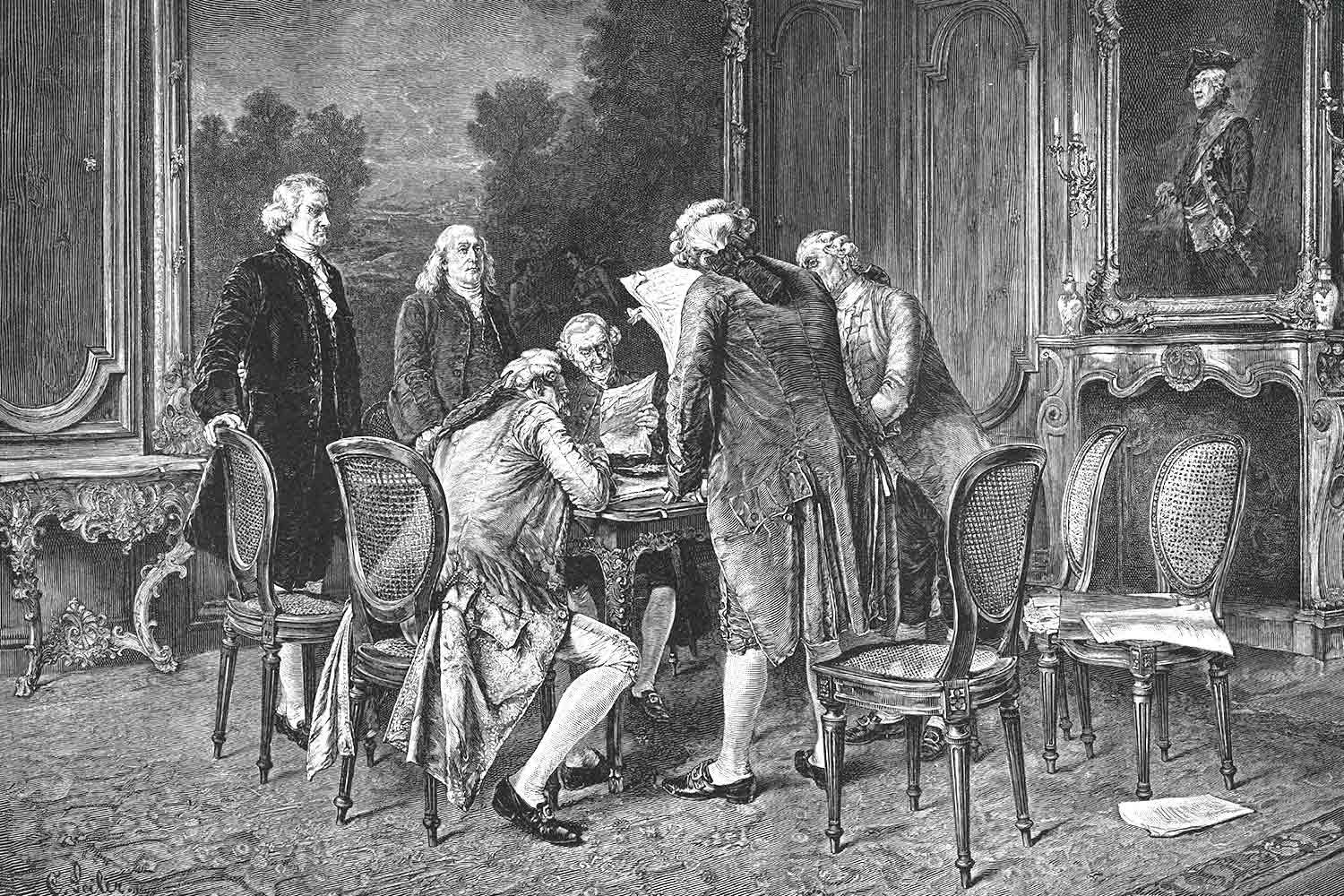

Benjamin West. “American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain.” Winterthur Museum.

Adams and Jay would not be put off. Together, these two patriots quickly opened direct talks with the British, bypassing the French and Benjamin Franklin, their pro-French fellow delegate.

On their own, they secured incredibly generous terms from England, including all the land between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes extending to the Mississippi being granted to America, navigation rights on the Mississippi, and fishing rights off Newfoundland. But most importantly, the British officially recognized American independence.

This agreement, known as the Treaty of Paris, was signed by the American delegation (Adams, Franklin, and Jay) and British representative David Hartley on September 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution.

Interestingly, Adams and Franklin were the only two men who were there at the beginning and the end of the American Revolution, signing both the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Paris.

In 1785, Adams, who was living in Paris and had recently been joined by his wife Abigail and daughter Nabby, was named by Congress as the first United States ambassador to England. Known as the Court of St. James because the diplomatic corps met in London’s St. James Palace, this important post was emblematic of the trust Congress felt in Adams.

Not surprisingly, the reception Adams received from the English was a bit chilly. Imagine the King and his ministers having to cordially greet and deal with the man who they felt was most responsible for the American Revolution.

Adams was nervous before his first meeting with King George, but all went well. The King mentioned he had heard Adams was not too attached to France. Adams responded, “I must avow to your Majesty, I have no attachment but to my own country.” King George replied, “An honest man will never have any other.” Well said on both parts.

After three unproductive years, Adams and his family sailed from England for the last time in April 1788 to a well-deserved joyous homecoming. For the last ten years, John Adams had been away from America for all but a few months.

In that time, he had traveled over 29,000 miles at a time when travel was not easy, secured loans from the Dutch to keep our government afloat, and negotiated the treaty that ended our War for Independence which essentially doubled the size of our young nation. Not bad for a guy who believed he was unsuited to be a diplomat.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should the John Adams’ diplomatic efforts matter to us today? John Adams arguably achieved more for the United States than any other of our early diplomats. His tireless work secured financial assistance from the Dutch when our nation needed it most and obtained extremely generous terms from the British in the Treaty of Paris. Moreover, he willingly sacrificed ten years of his life away from his home and family for the benefit of America. For John Adams, the ask from his country was never too great.

SUGGESTED READING

In 1962, Page Smith published John Adams, a detailed account of our nation’s second President. This well written narrative in two volumes tells the story of Adams’ impressive life and how he impacted America during its founding era.

PLACES TO VISIT

If you visit Washington, DC, you may want to stop by the Netherlands Carillon, a beautiful tower of fifty bells, near the Marine Corps War Memorial. Given as a gift by the Dutch to America for liberating the Netherlands in World War II, it is also a reminder of our strong relationship stretching back to John Adams in the 1780s.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.