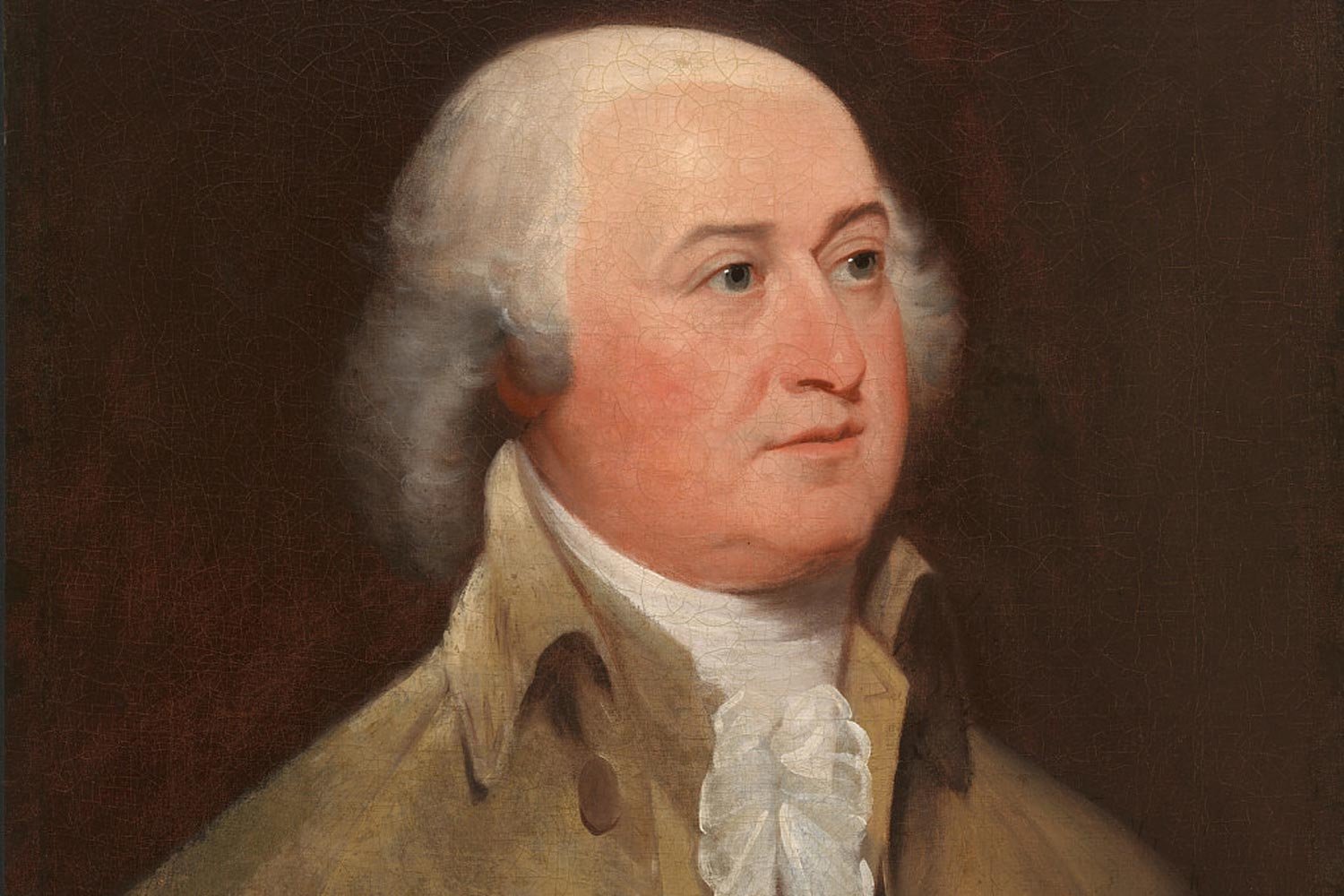

The Rise of John Adams

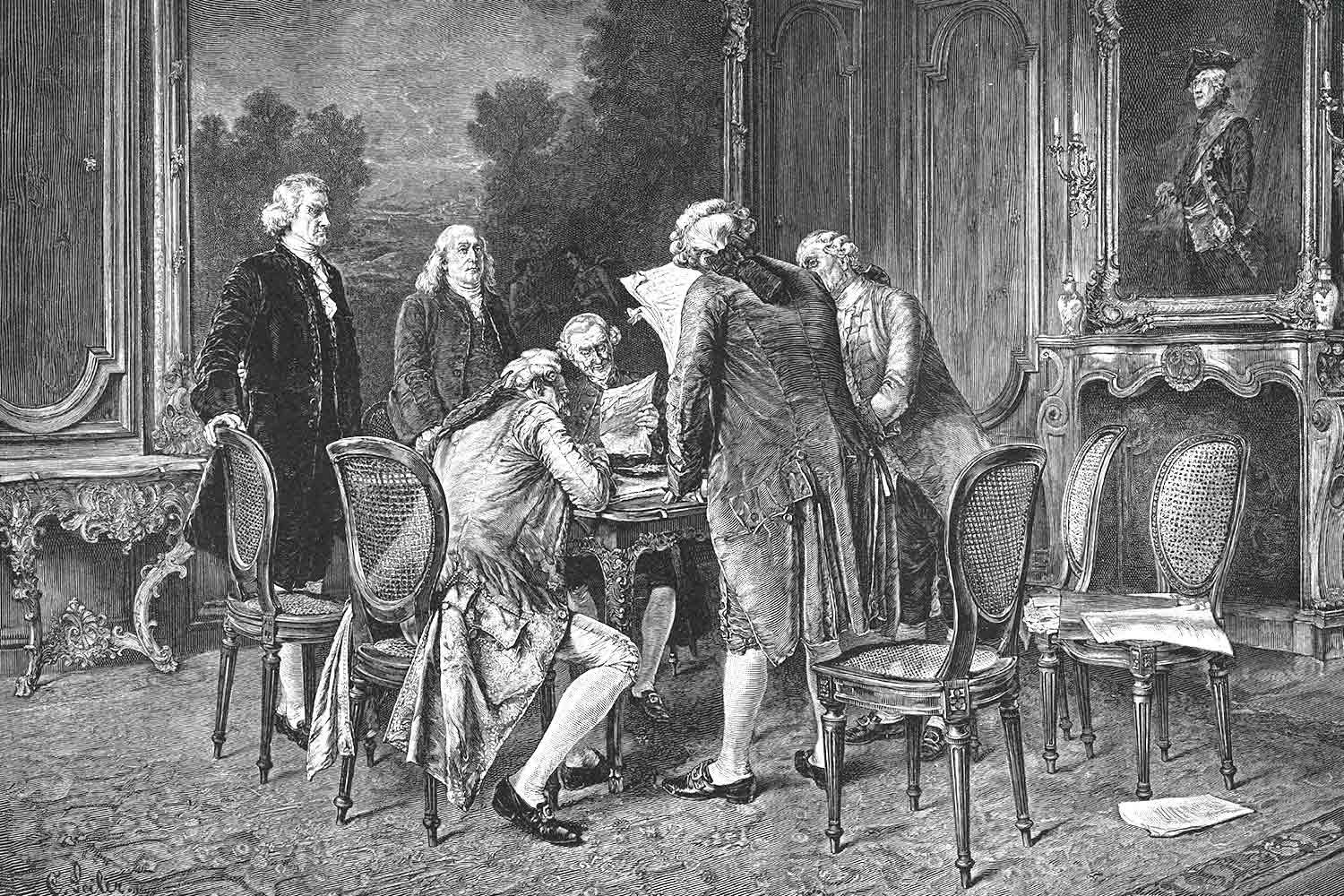

John Adams was one of America’s greatest patriots from the Founding generation. From gaining unanimous agreement from state delegations to the Declaration of Independence to obtaining favorable terms in the Treaty of Paris, Adams may have contributed more to America gaining her independence than anyone other than George Washington.

Adams was born on October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts to John Adams, Sr. and Susanna Boylston. The senior Adams was a Harvard-educated farmer who made shoes (a cordwainer) to supplement the family’s income. He also was a deacon in the local church, a selectman in the town council, and a lieutenant in the militia, instilling in young John a commitment to the greater community. The family household was run in the strict Puritan fashion, with a focus on hard work, honest living, and good morals, traits that shaped the fine character and straightforward manner, but also stubborn nature, Adams so frequently displayed in later life.

Unlike other early leaders such as George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, Adams received a full formal education, beginning at age six and continuing until he entered Harvard in his sixteenth year in 1751. His father had hoped for John to study for and enter the ministry upon graduation, but this profession held little interest for the son who craved the blessings of fame more than those associated with the pulpit.

Adams graduated from Harvard in 1755 at the age of twenty and took a job as a schoolteacher in Worcester, Massachusetts. But after just one year, Adams knew the classroom was not for him and he began to study law under James Putnam, a local attorney. Three years later, Adams was admitted to the Massachusetts bar and set up his practice in his hometown of Braintree.

In 1764, after a lengthy courtship, John Adams married Abigail Smith, his third cousin. Abigail, who was not quite twenty when they were wed, was about five feet tall with brown hair and brown eyes. Theirs was to be a wonderful marriage between two compatible people who were devoted to each other and shared a common view of the world. They were true partners in life and had six children, four of whom survived to adulthood including their oldest boy, John Quincy, who would become our nation’s sixth president.

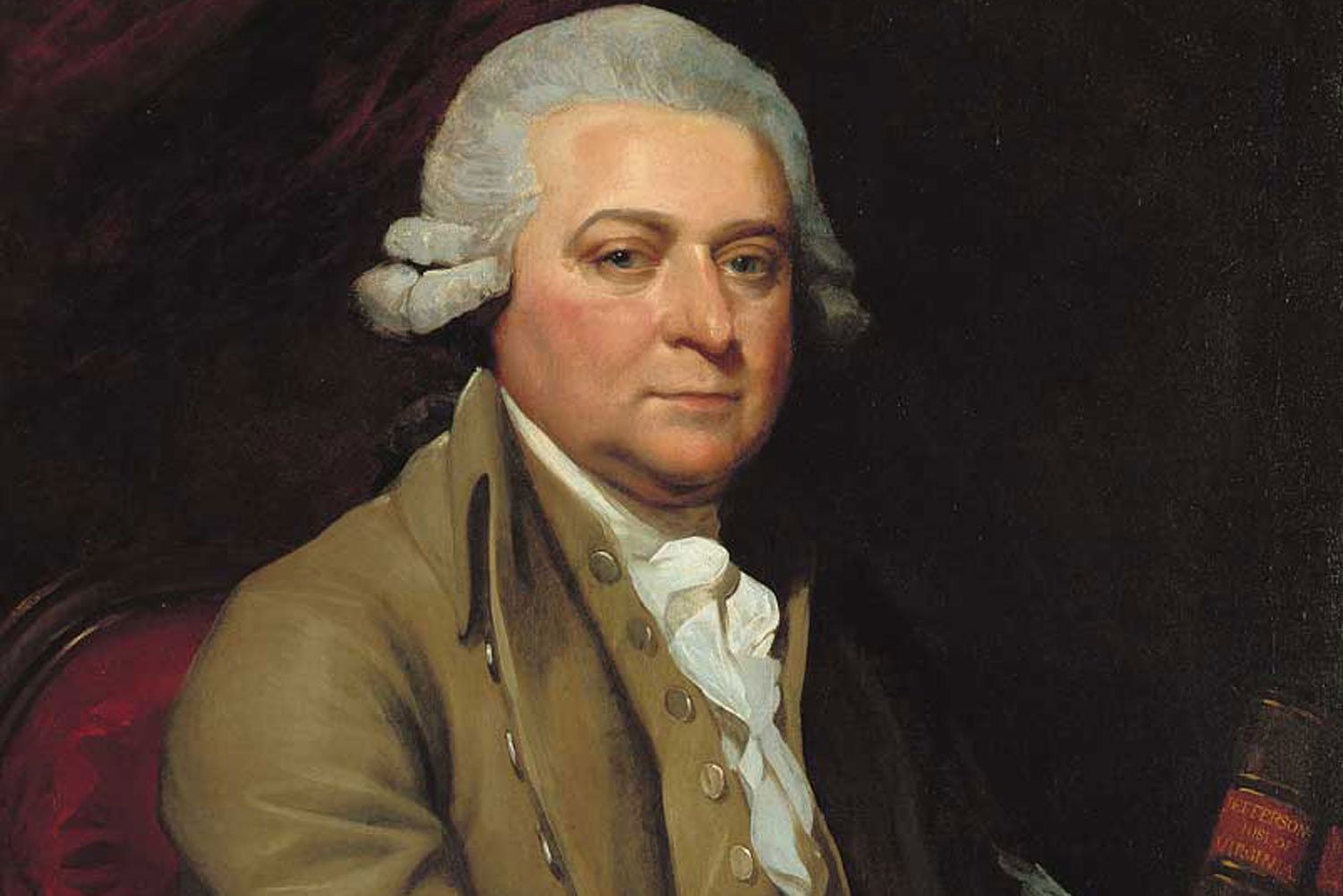

At about this same time, Parliament began to pass a series of revenue laws including the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765. Adams viewed these measures as encroachments on the liberties of American colonists and began to develop his thoughts of the proper relationship between Great Britain and the colonies. Like other colonial leaders, Adams recognized these bills represented more than simply revenue grabs by the Crown. There was the larger constitutional question of whether Parliament had the right to tax the American colonists since they were not represented in that legislative body.

In a series of articles under the pen name “Humphrey Ploughjogger,” Adams argued that the Stamp Act was invalid due to the lack of colonial representation in Parliament. These writings, which were printed in the Boston Gazette, as well as in London (under the title The True Sentiments of America), gained Adams quite a bit of notice in Massachusetts and in other parts of North America.

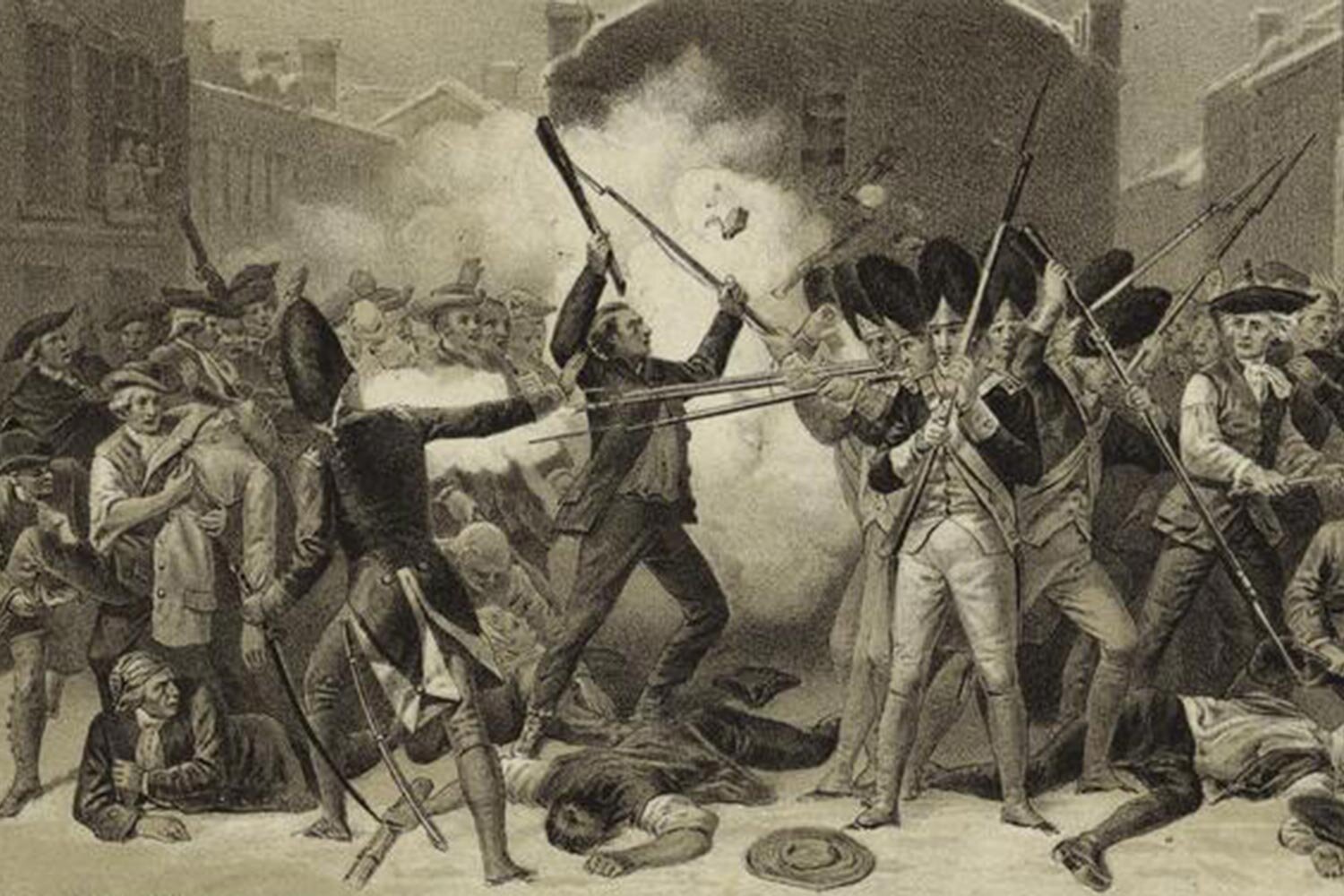

Following resistance from the colonies, the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, but strong emotions continued to fester under the surface. This discontent came to a boil on March 5, 1770, in an incident known to history as the Boston Massacre which started with an angry mob of Bostonians pelting British soldiers standing guard with ice and rocks, and the soldiers firing into the crowd, killing five men.

Alonzo Chappel. "Boston Massacre." New York Public Library.

The soldiers were arrested and charged with murder, and, when no one else would take their case, John Adams stepped forward, reasoning that all men deserved legal counsel. Adams was brilliant in his defense of these men and gained their acquittal. While Adams was unpopular for a brief period, his principled stand and forceful argument enhanced his reputation as a man of ability, honesty, and integrity.

After Parliament passed the Tea Act in the spring of 1773, simmering tensions again boiled over resulting in the iconic American event known as the Boston Tea Party in which residents tossed 92,000 pounds of British tea into Boston Harbor.

Parliament pushed back against this unlawful destruction of private property, shutting down the port of Boston and revoking the charter of Massachusetts. As a result, colonial leaders assembled at the First Continental Congress in 1774 to address the growing crisis, and Adams was selected to represent Massachusetts. Moderates such as John Dickinson controlled the day, and it was agreed to try to find a peaceful solution to the growing rift with England.

But after the Battles at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the die was cast and at the Second Continental Congress. Adams’ eloquent and forceful arguments dominated the discussion, culminating in the unanimous approval by all state delegations of the Declaration of Independence. For the next twenty years, John Adams worked tirelessly to help his country gain its independence and then build the foundation for future growth of the United States.

Next week, we will discuss the XYZ affair during the Adams administration. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

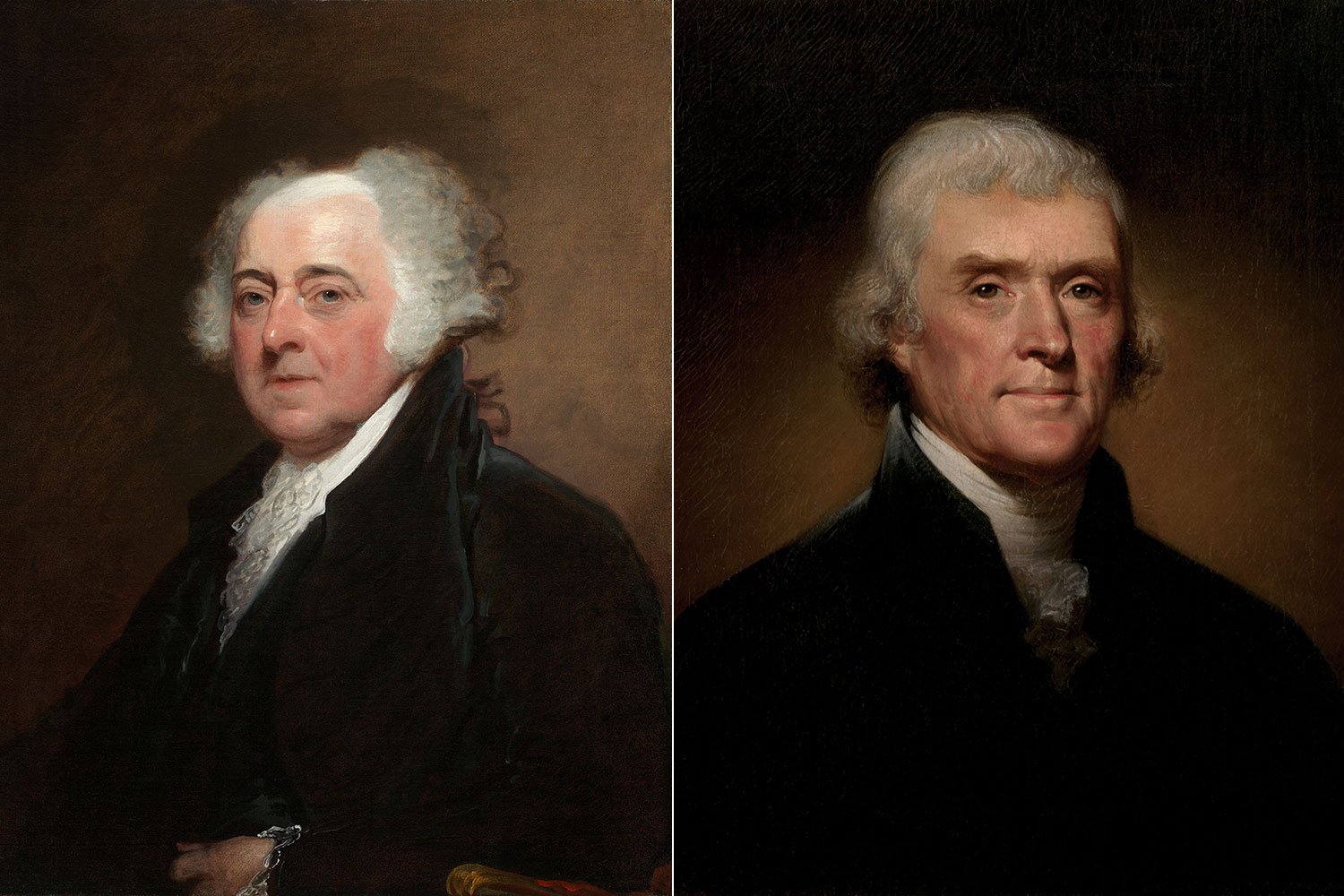

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.