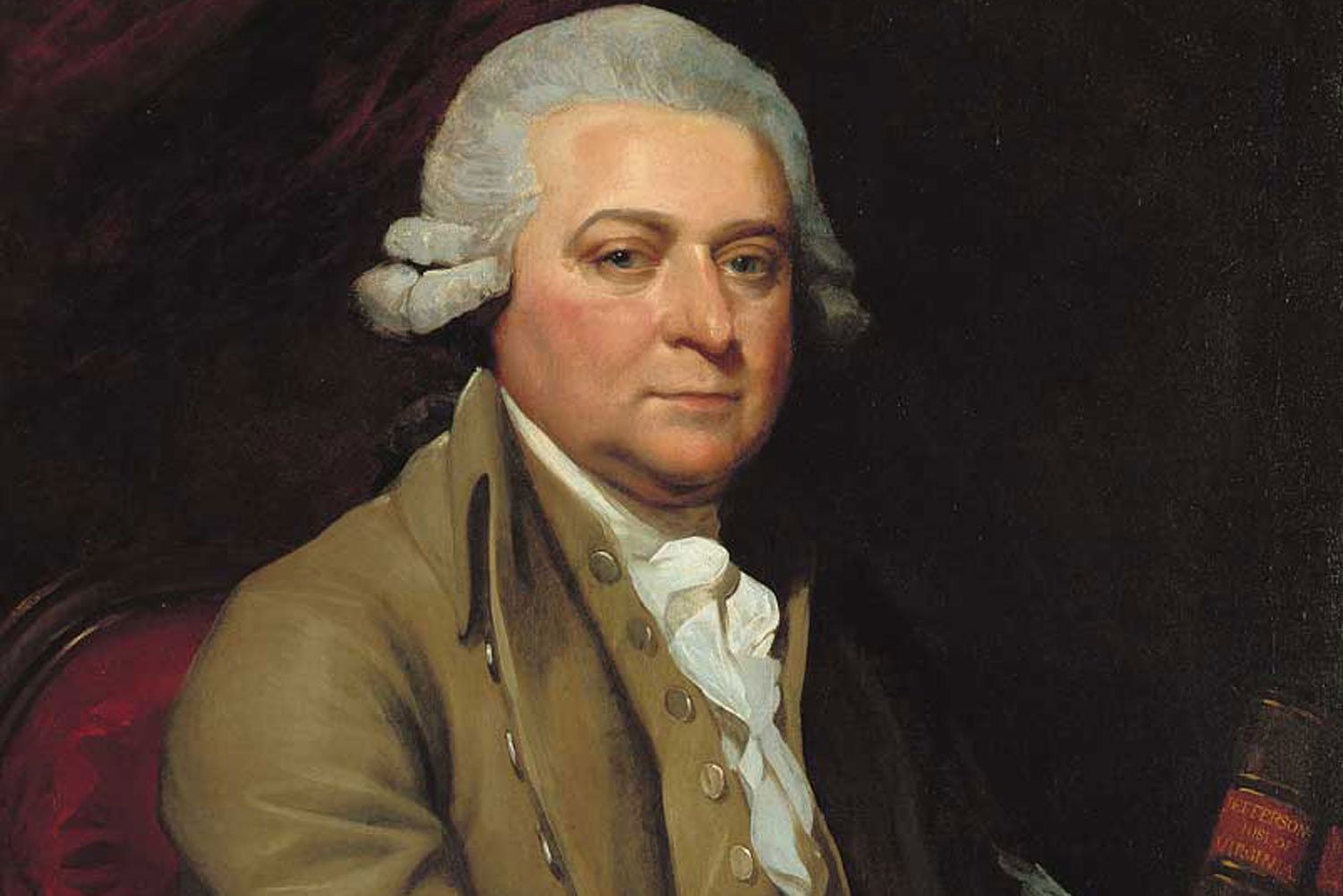

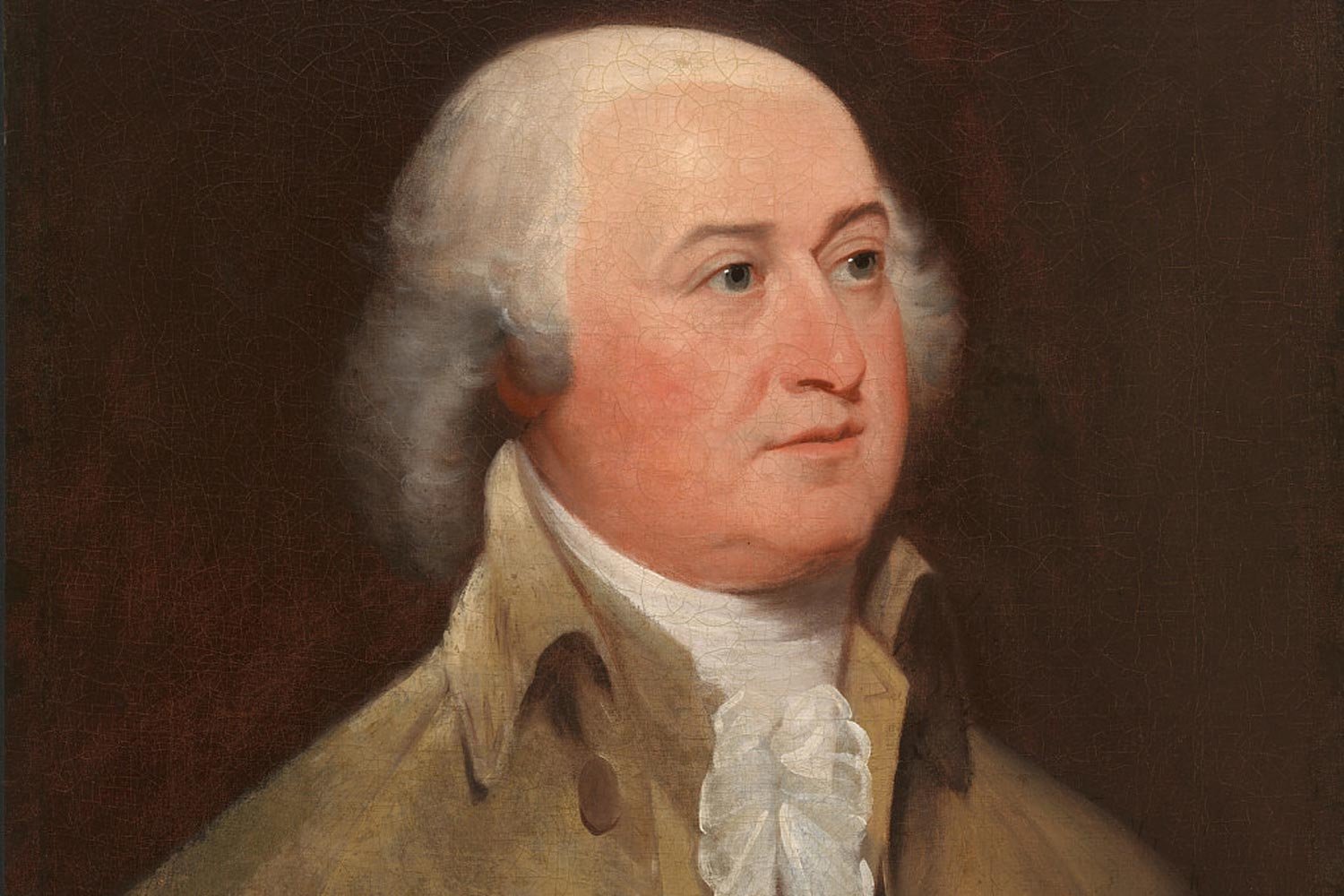

John Adams and the Presidential Election of 1796

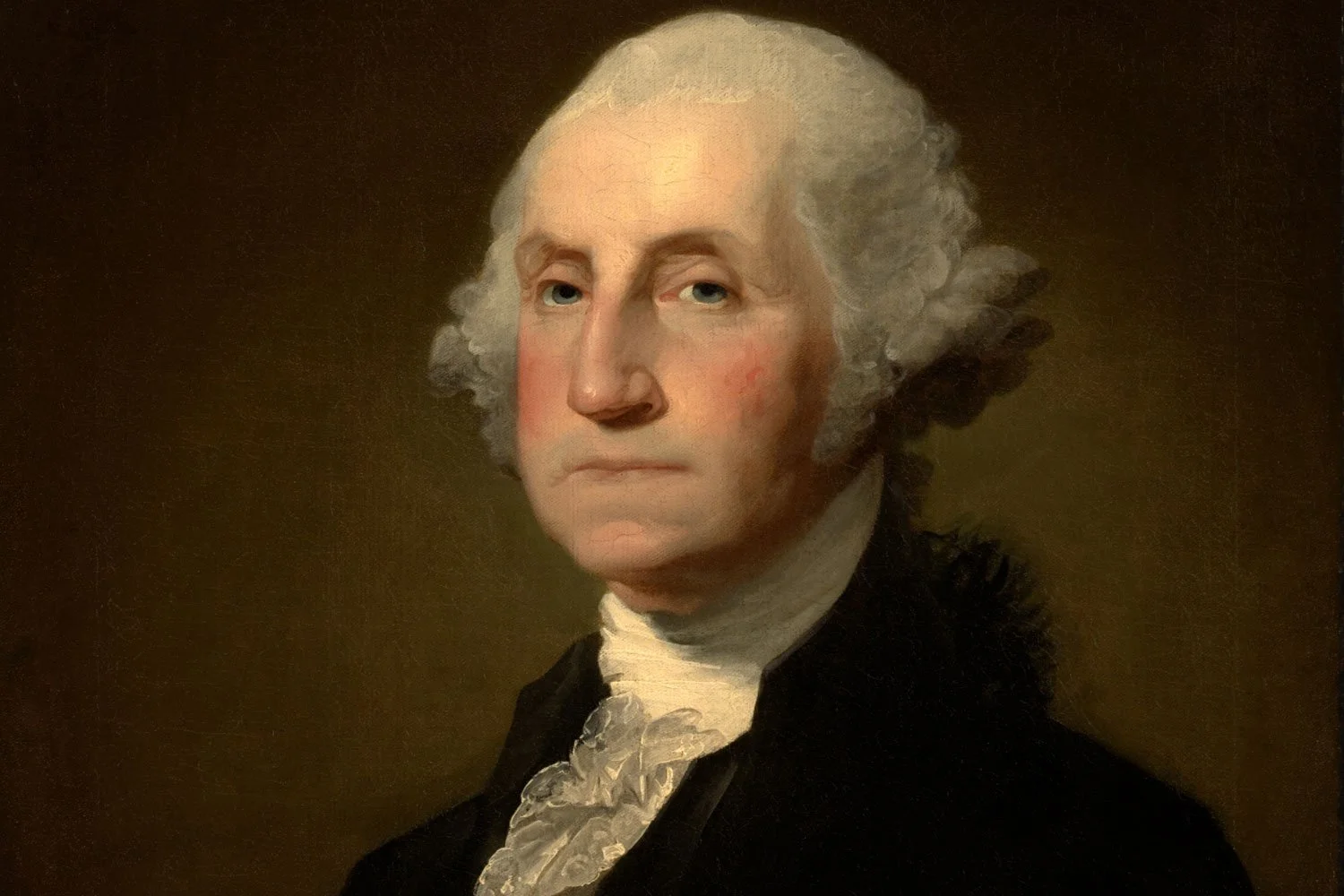

After eight years as Vice President under George Washington, John Adams hoped to succeed the Father of our Country as President of the United States. His successful election in 1796 gave him his chance.

Unlike our nation’s first two elections (1788-89 and 1792) in which George Washington essentially ran unopposed and was unanimously elected, the election of 1796 was America’s first contested election for President.

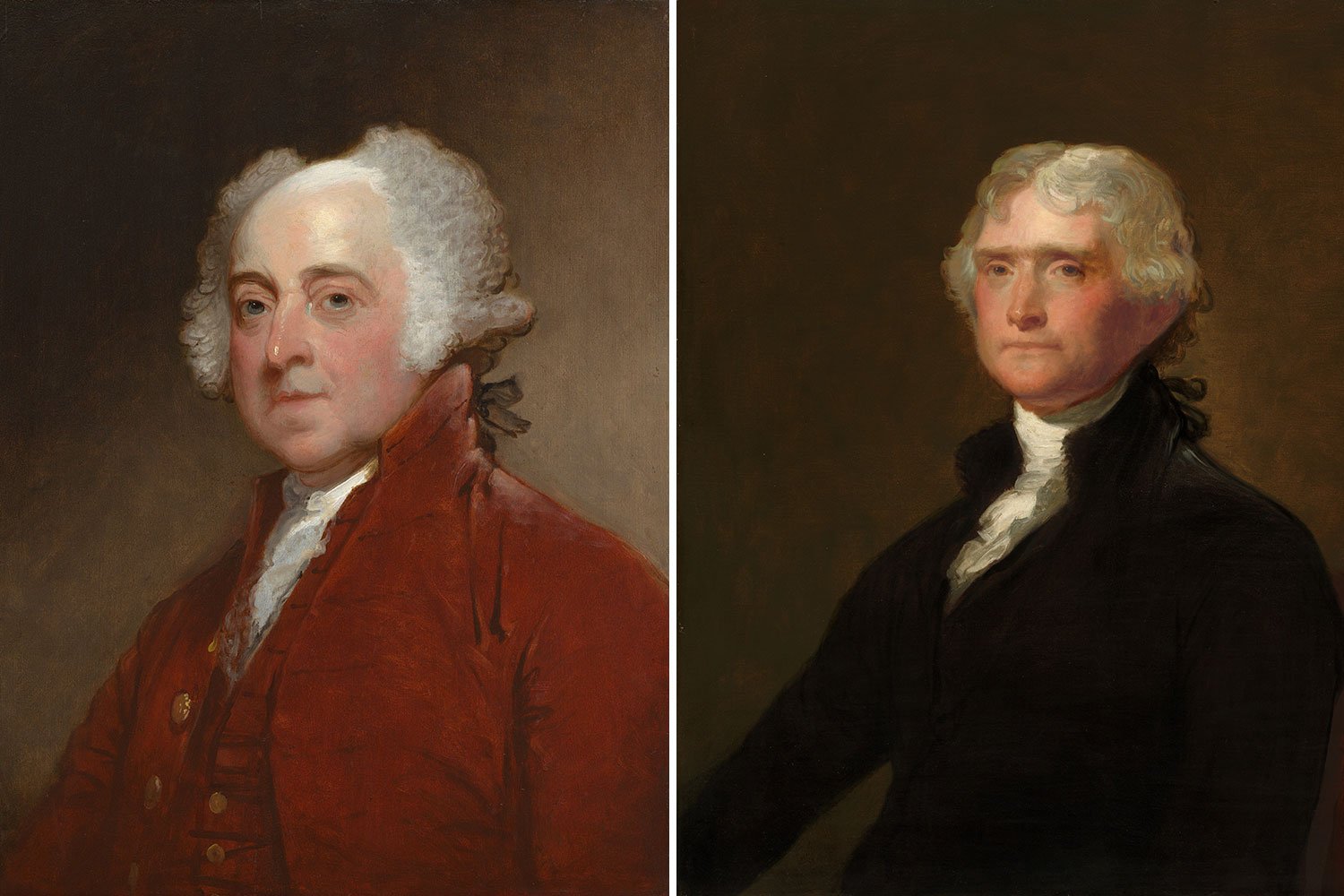

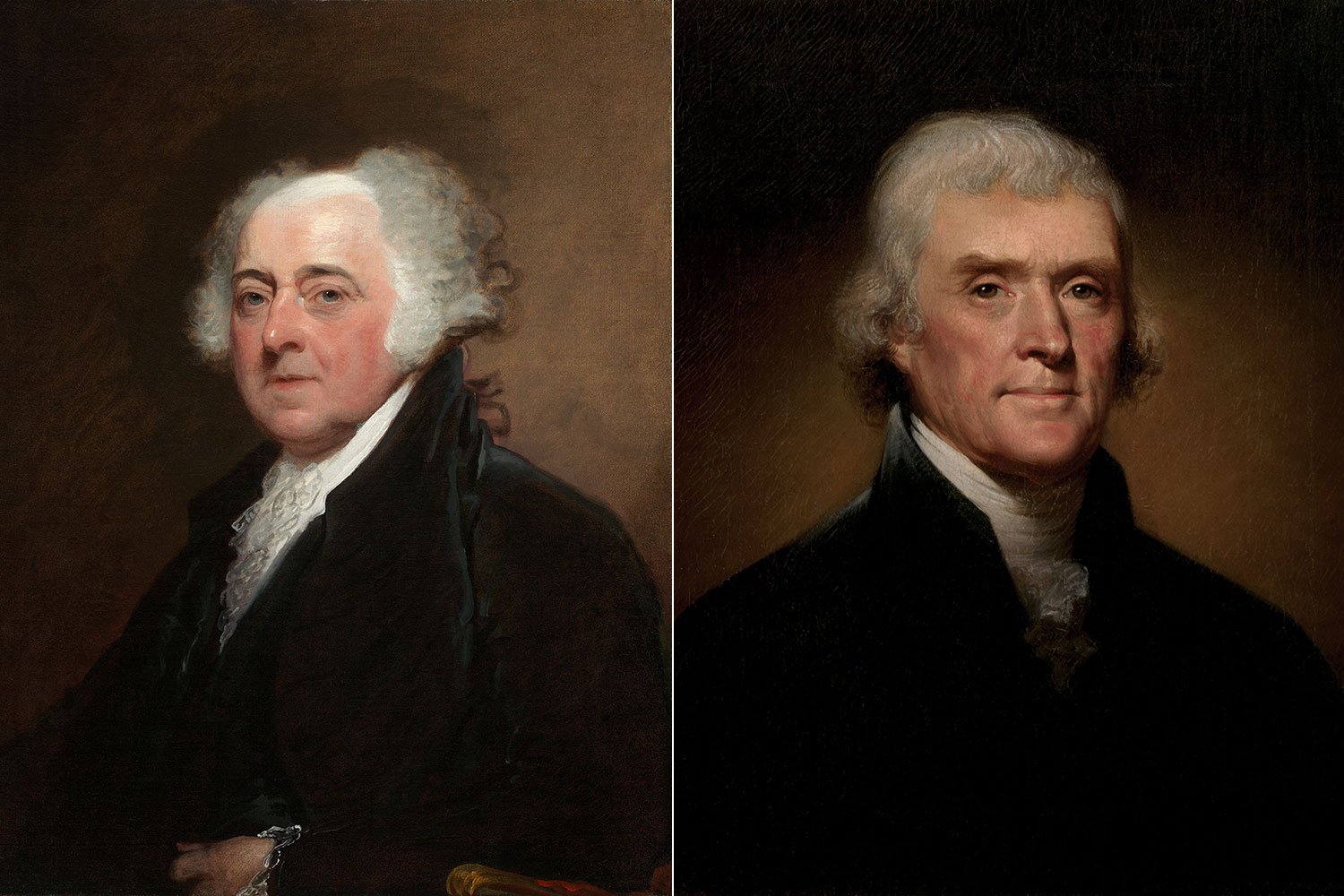

Without Washington as a unifying symbol, the electorate and the other Founding Fathers split into two distinct camps or parties. Adams was the candidate of the Federalist party, while Thomas Jefferson emerged as the favorite of the Democratic-Republicans (commonly called Republicans).

For the most part, the election split along geographic lines with Adams and the Federalists capturing the north and Jefferson’s Republicans the southern states plus Pennsylvania. The final tally of electoral votes was 71 for Adams and 68 for Jefferson.

This election was held under the original rules of the Constitution in which the top vote getter (Adams) was declared President and the second highest (Jefferson) was named Vice President. Naturally, having the President and Vice President from opposing political parties was a recipe for trouble.

Although this problem was fixed in 1805 with the passage of the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, it would prove to be a very real problem for the newly elected President, as Vice President Jefferson worked to undermine the Adams’ administration for the next four years.

Jefferson went so far as to hire newspaper editors to run anti-administration articles, and he met secretly with French officials to keep them informed of decisions made by Adams and the federal government. Not exactly a devoted subordinate.

The Federalist party tended to be pro-British and favor a strong central government. They wanted a standing army and centralized control of the economy. Conversely, Jefferson’s Republicans were fanatically pro-French despite the bloody French Revolution, and they favored strong states’ rights. It was like mixing oil and water.

In any event, on March 4, 1797, John Adams was sworn in as President and began a four year stretch that would be dominated by a deteriorating relationship with France.

One of President Adams’ early decisions was to retain President Washington’s cabinet officers (Timothy Pickering as Secretary of State, Oliver Wolcott as Secretary of Treasury, James McHenry as Secretary of War, Charles Lee as Attorney General).

Although Adams was not close to these men, he felt keeping them would provide continuity to the country. It was a decision he would live to regret as these all but Charles Lee proved to be more loyal to Alexander Hamilton, the leader of the Federalist Party and Washington’s former Secretary of Treasury, than to Adams.

Gilbert Stuart “George Washington.” The Clark.

Additionally, Adams stayed true to President Washington’s policy of neutrality in the expanding war between England and France, our former ally. France saw this policy and the recently approved Jay Treaty which settled our major differences with England as proof America was supporting the British.

Consequently, France began an aggressive campaign to capture American merchant ships. From October 1796 to June 1797, French vessels captured over 300 American ships, about 6% of our entire merchant fleet. Unfortunately, the United States was powerless to respond.

Due to the cost of maintaining a navy and opposition under the Articles of Confederation to programs that strengthened federal operations, the last United States vessel from the American Revolution had been decommissioned in 1785.

This lack of a naval presence was troubling to many when the new Constitutional government was formed. Consequently, in 1794, Congress passed the Naval Act of 1794 which authorized the building of six frigates (medium sized warships). However, due to various delays, none of the vessels were put to sea until 1797 under the Adams administration when the troubles with France spurred them to action.

Worried that emotions would push France and America into an open war, President Adams sent a delegation (John Marshall, Charles Pinckney, and Elbridge Gerry) to France to talk things over. It did not go well.

Next week, we will discuss this diplomatic effort and other key moments of President Adams’ time in office. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

On May 15, 1776, the fifth Virginia Convention meeting in Williamsburg passed a resolution calling on their delegates at the Second Continental Congress to declare a complete separation from Great Britain. Accordingly, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose and introduced into Congress what has come to be known as the Lee Resolution.