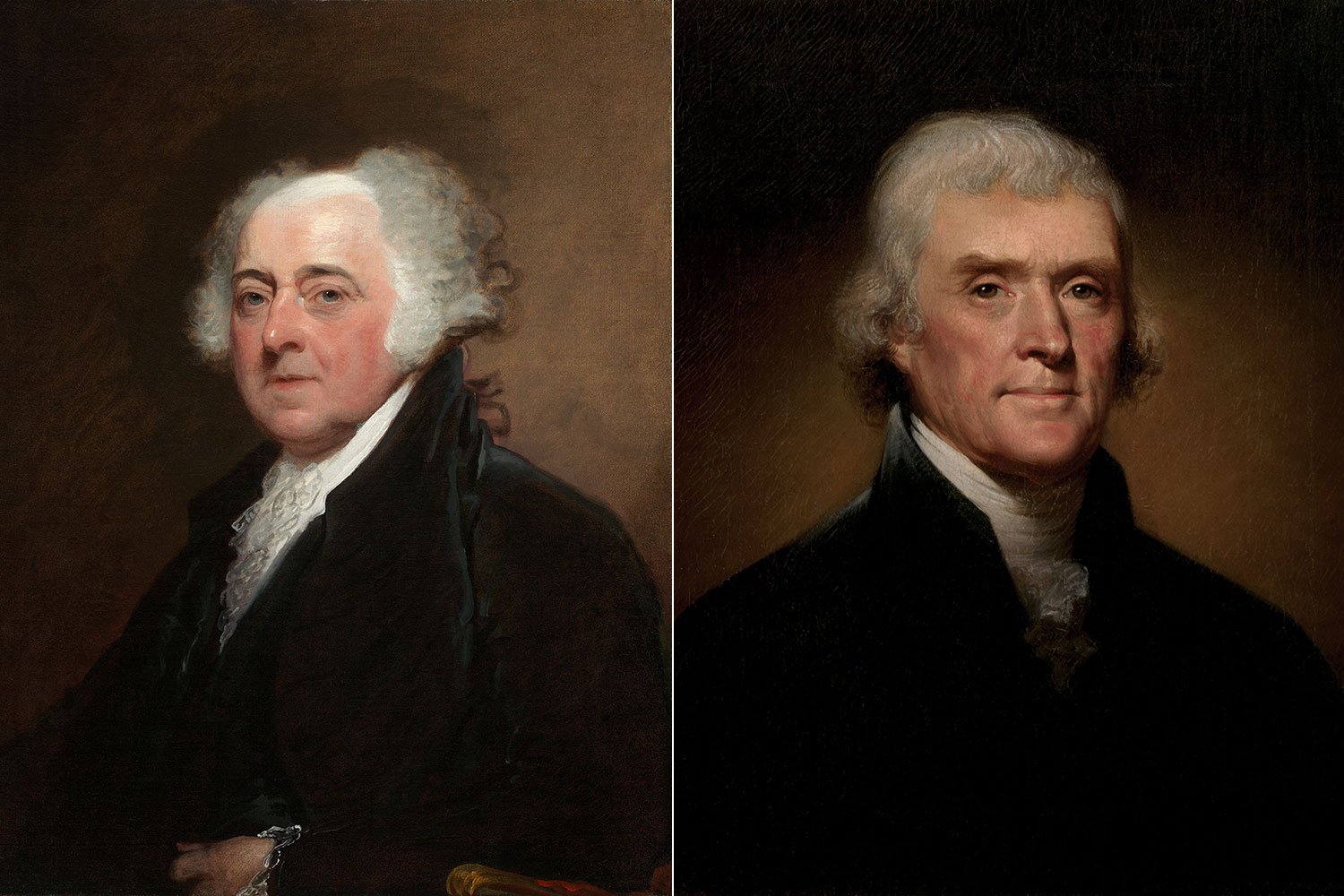

The Election of 1796

After serving two terms as President, George Washington decided to not seek a third and instead retire from public life. His decision led to the country’s first contested presidential election in the fall of 1796, pitting Thomas Jefferson against Vice President John Adams. Arguably, no presidential election in the history of the United States has ever featured a choice between two such American titans.

Jefferson emerged as the favorite of the Democratic-Republicans who were fanatically pro-French and favored strong states’ rights and an agrarian economy. Jefferson had ably served in many public positions since being a member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1769. He had represented Virginia at the Second Continental Congress and been the primary author of the Declaration of Independence.

During the American Revolution, Jefferson had served two terms as Governor of Virginia, the country’s largest and most populace state. After the war, Jefferson was Minister to France from 1785-89 and President Washington’s Secretary of State for one term. After retiring from public life in December 1793, Jefferson spent much of his time at his beloved home Monticello creating the Democratic-Republican party with the assistance of his protégé James Madison.

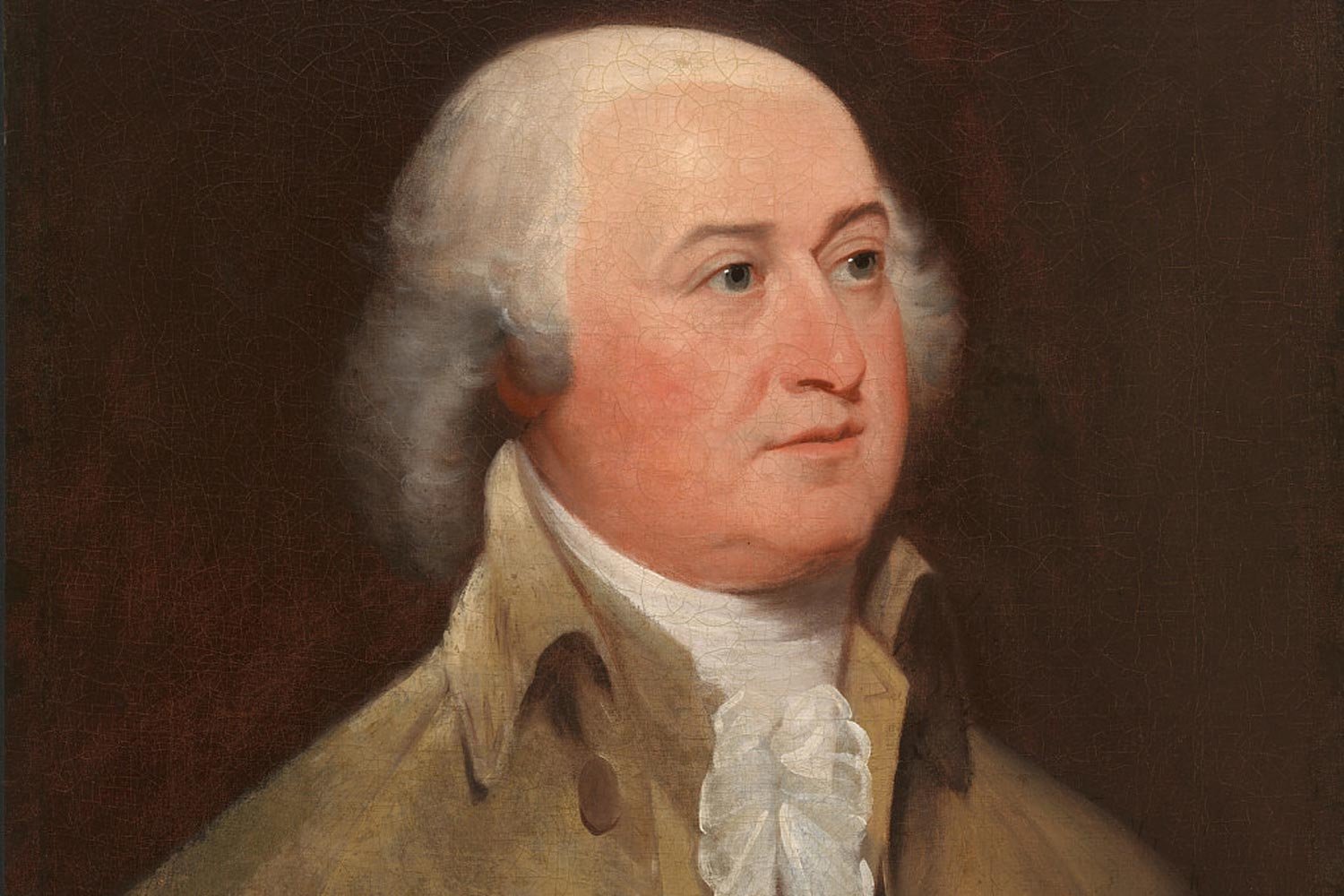

John Adams was the favorite son of the Federalist Party that tended to be pro-British and favored a strong central government with a standing army and centralized control of the financial system. As impressive as Jefferson’s credentials were, Adams’ were arguably even more so. Adams had represented Massachusetts at the First and Second Continental Congresses and had been responsible for securing the unanimous approval of each state delegation to the Declaration of Independence. Adams was also the primary author of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780.

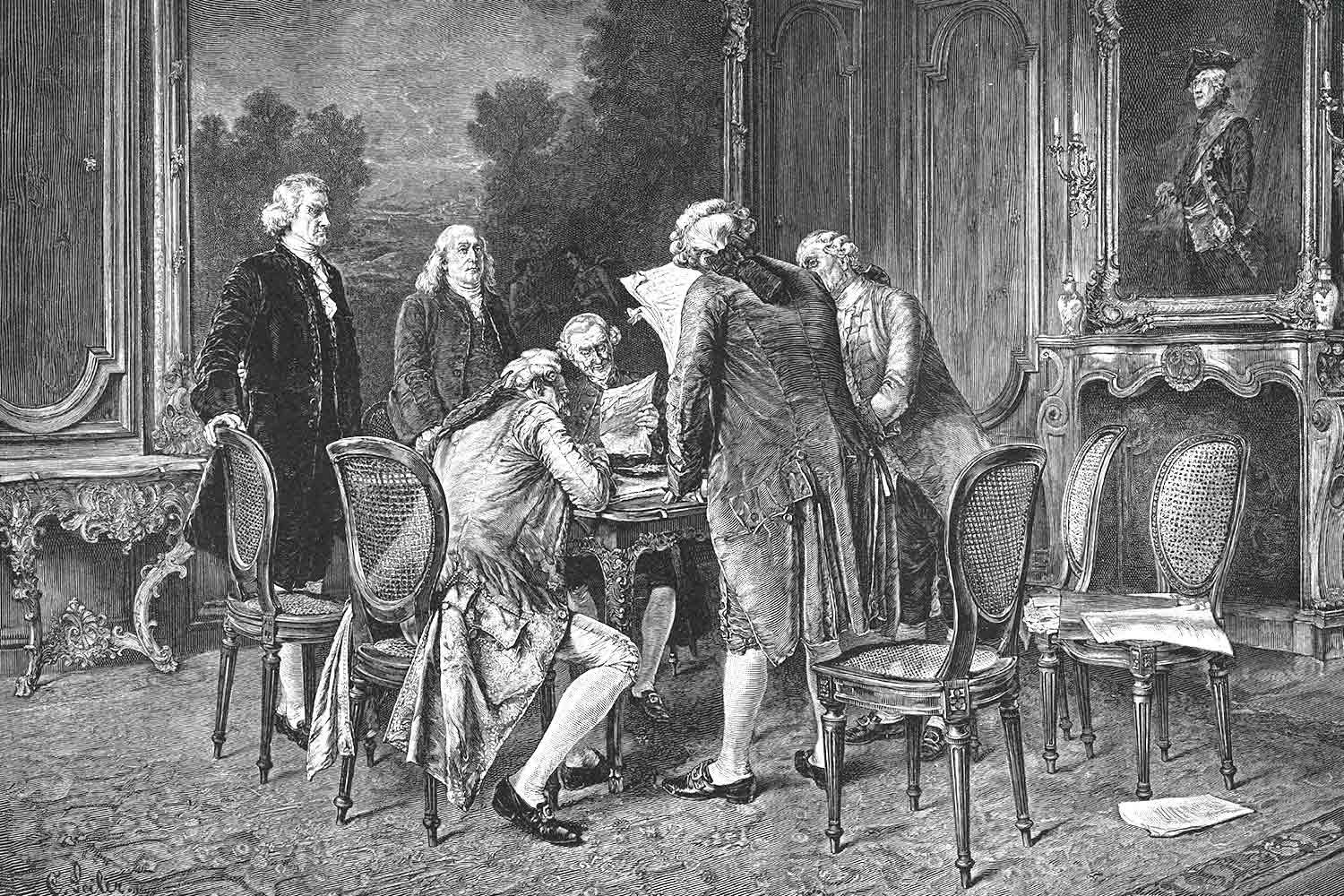

During the war, Adams traveled overseas and obtained much needed loans from the Dutch and negotiated generous terms for the United States in the Treaty of Paris. Following the war, he had served three years as Ambassador to Great Britain and, most recently, had been the Vice President of the United States for eight years.

The election would be the first real test of the new system devised at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Article II of the Constitution stated that the President would be chosen by “a number of Electors equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the state may be entitled in Congress” and that each elector shall “vote by ballot for two persons.” Furthermore, “The person having the greatest number of votes shall be President” and the person with the second highest count would be Vice President.

That system was fine in 1787 when the Constitution was created, and the country was as close to one big happy Patriotic family as it would ever be, and political parties were viewed by all with disdain. While states made all their own decisions and the federal government was powerless under the Articles of Confederation, New Englanders did what was best for them and Southerners did the same. Now that the new Constitutional government could make a policy that affected both regions, people started to coalesce into groups that would support their regional interests, hence the birth of political parties.

John Trumbull. "Thomas Pinckney." National Portrait Gallery.

The two parties that developed out of this new reality were the Federalists centered in New England and the Democratic-Republicans concentrated in the south. Because electors were tasked with casting votes for two people, each party put forth two candidates, one intended to be the President and the other the Vice President. In this case, the Federalists nominated Adams and South Carolinian Thomas Pinckney while the Democratic-Republicans supported Jefferson and Aaron Burr from New York. The problem was that if all Federalist electors voted for both their candidates and the Democratic-Republicans did the same, no matter which party won the election, there would always be a tie.

Consequently, party leaders negotiated behind the scenes to get some of their electors to waste their second vote so the candidate they did favor would be elected President. The danger was that if too many wasted votes were cast by the party electors, the other party’s primary candidate might garner the second highest vote total and become Vice President, thus creating a situation in which the President and Vice President were from opposing parties.

Although the Constitution explained how the President would be chosen, it did not address how candidates were to campaign or if they were to do so at all. To many, the office of President of the United States was considered too dignified for contestants to participate in the seedy business of electioneering. As such, neither Adams nor Jefferson actively campaigned, leaving the mudslinging and name calling to their surrogates which they took on with a vengeance. While Adams was called “His Rotundity” and declared the “champion of kings, ranks, and titles,” Jefferson was denounced as an atheist, a coward, and morally unfit.

For the most part, the election split along geographic lines with Adams capturing the north and Jefferson the southern states, plus Pennsylvania. In the final tally, Adams received 71 votes, Jefferson 68, Pinckney 59, and Burr 30. Thus, John Adams was declared President and his opponent, Thomas Jefferson, was named Vice President. That odd situation would prove to be a very real problem for the newly elected President, as Vice President Jefferson worked to undermine the Adams administration for the next four years.

Despite those headwinds, John Adams was anxious to get started as the nation’s chief executive, completing an exceptional journey from his upbringing in Braintree, Massachusetts.

Next week, we will discuss the early life of John Adams. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.