The Legacy of John Adams

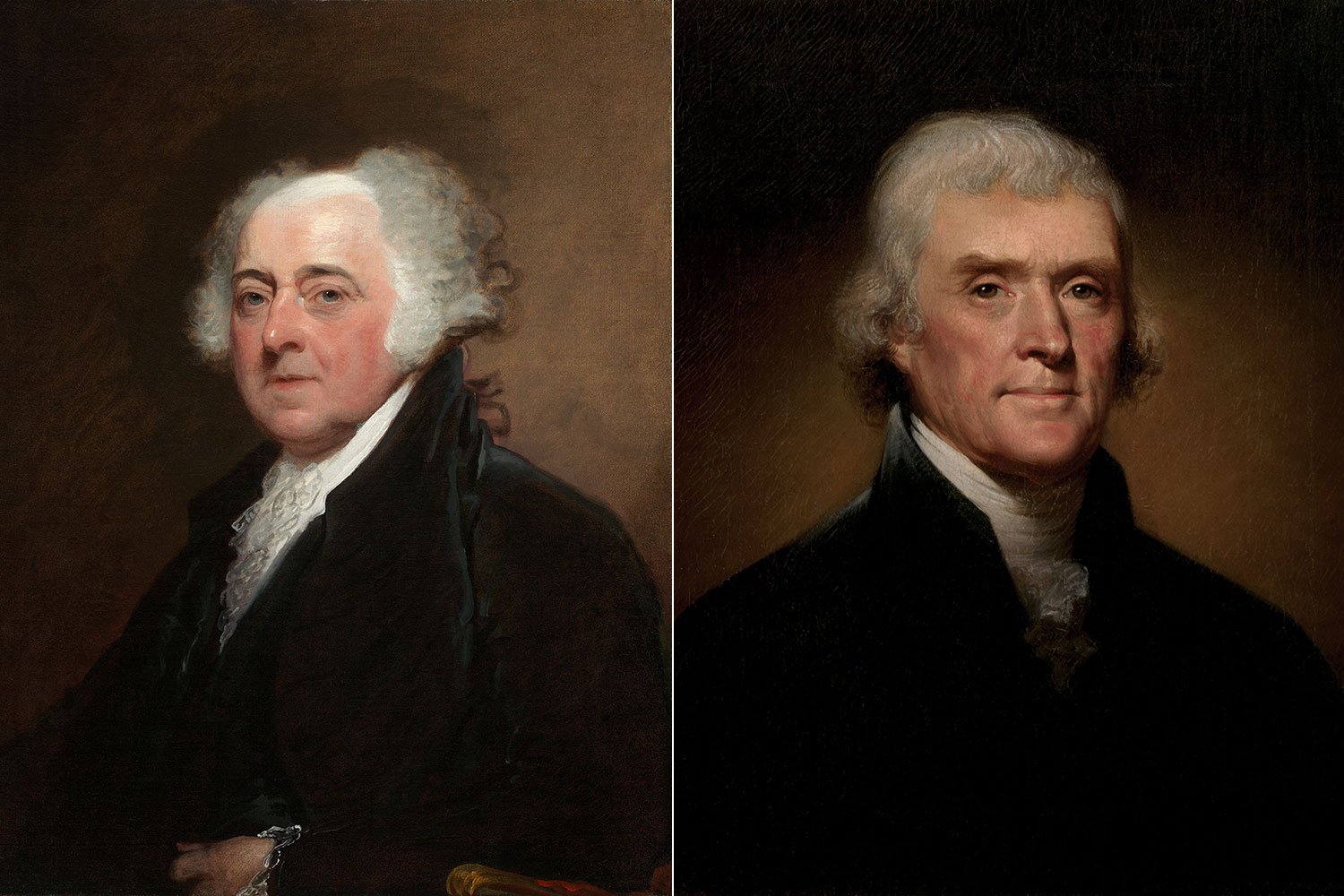

John Adams’s loss to Thomas Jefferson in the presidential election of 1800 was a great disappointment for Adams as he felt he deserved another term based on his accomplishments during his four years as President. But Adams accepted the verdict of the Electoral College and looked forward to the next phase of his life.

Adams spent his final months in office trying to improve the operations of the federal court system, including the Supreme Court. He used his remaining influence to get Congress, still controlled by his Federalist Party, to pass the Judiciary Act of 1801, although newly elected President Thomas Jefferson would rescind most of its provisions.

More importantly, President Adams named Secretary of State John Marshall as chief justice of the Supreme Court, a position Marshall held until his death in 1835. Marshall was the longest serving chief justice in our nation’s history and, during his tenure, established the judiciary as an independent and co-equal branch of government, alongside Congress and the president.

At 4 a.m. on March 5, 1801, John Adams left the recently completed President’s Mansion (now known as the White House), which due to construction delays, had only been occupied by Adams for four months. He chose not to attend Thomas Jefferson’s swearing in ceremony, one of six Presidents (John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Martin Van Buren, Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Donald Trump) who did not attend their successor’s inauguration.

He returned home to Peacefield, his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts, where Abigail was anxiously awaiting him. At the age of sixty-five, President Adams, who was at the center of the revolutionary hurricane for the past twenty-five years, was ready for a rest. He spent his time tilling the land and he stayed out of public political squabbles.

In 1812, Adams rekindled his friendship with Thomas Jefferson at the instigation of Benjamin Rush, a good friend of both men. Rush advised Adams, who was then seventy-seven years old, to open the dialogue before it was too late. Although Adams had not corresponded with or spoken to his revolutionary compatriot for twelve years, he agreed and sent a letter to Jefferson who quickly responded. The two former revolutionary leaders continued their engaging correspondence for the rest of their lives. This collection of 158 letters (109 by Adams and 59 by Jefferson) between our second and third presidents is a real treasure to America.

Interestingly, these two men, joined in life on so many matters, died on the same day, July 4, 1826, our nation’s fiftieth birthday. While Jefferson became one of the best-known Founding Fathers, John Adams faded somewhat into obscurity. That seems odd considering Adams’s numerous accomplishments and, that for a quarter of a century, Adams devoted his life to serving the country he loved. He once famously stated, “Sink or swim, live or die, survive or perish, I am with my country” and his record proves him out.

In 1775, Adams dominated the Second Continental Congress as a delegate from Massachusetts and was largely responsible for getting the Declaration of Independence unanimously approved by the state delegations. He also nominated George Washington to be the commander of the new Continental Army, ushering that indispensable man onto the national stage, where Washington became a man for the ages.

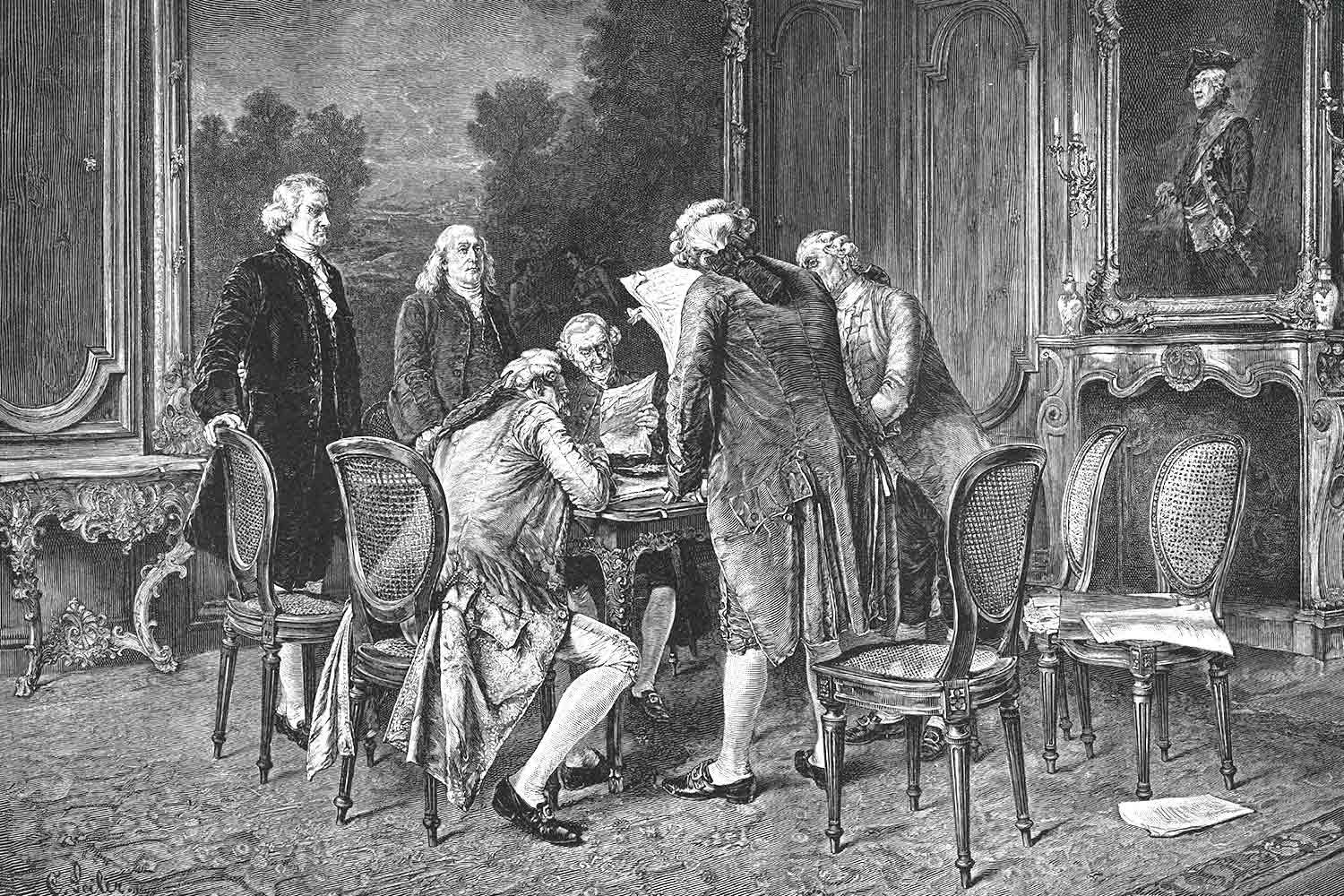

In the later stages of the war, when the nation was bankrupt and needing funds to survive, Adams obtained a large loan from Dutch bankers to keep our floundering government afloat. The following year, Adams and John Jay secured very favorable terms and recognition of the independence of the United States from the British in the Treaty of Paris of 1783, officially ending the American Revolution.

"Writing the Declaration of Independence 1776." Library of Congress.

Adams was then selected as the first United States Ambassador to King George and the Court of St. James, where he served from 1785-88. Although treated coldly by the British who viewed Adams as the primary catalyst for the American Revolution, Adams did his utmost to heal the wounds from the recently concluded war and tried to restore trade relations with America’s largest trading partner.

Adams returned home to a hero’s welcome in June 1788, just months before the United States would begin its new constitutional government. In the nation’s first presidential election later that fall, Adams received the second most electoral votes and became Vice President John Adams, a role he helped create and shape for others that came after him.

And of course, when President Washington left the public arena for the final time, Adams won the presidential election of 1796 against his former friend and now political rival Thomas Jefferson and became President John Adams, the leader of his beloved country. When John Adams was a young man, his goal was to achieve “honour or reputation” and become a “great man.” By all accounts, John Adams achieved his goals.

So why should John Adams’s legacy matter to us today? John Adams arguably did more to create and shape the United States than any other Founding Father, except for the incomparable George Washington. He was a critical player in practically every major event of our nation’s formative years; his efforts made America a better place.

John Adams was an incredibly gifted man who never put his own personal needs and desires above those of his country, and his devotion to the American cause remains an inspiration to Americans today.

Next week, we will discuss the election of 1800. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.