The Election of 1800

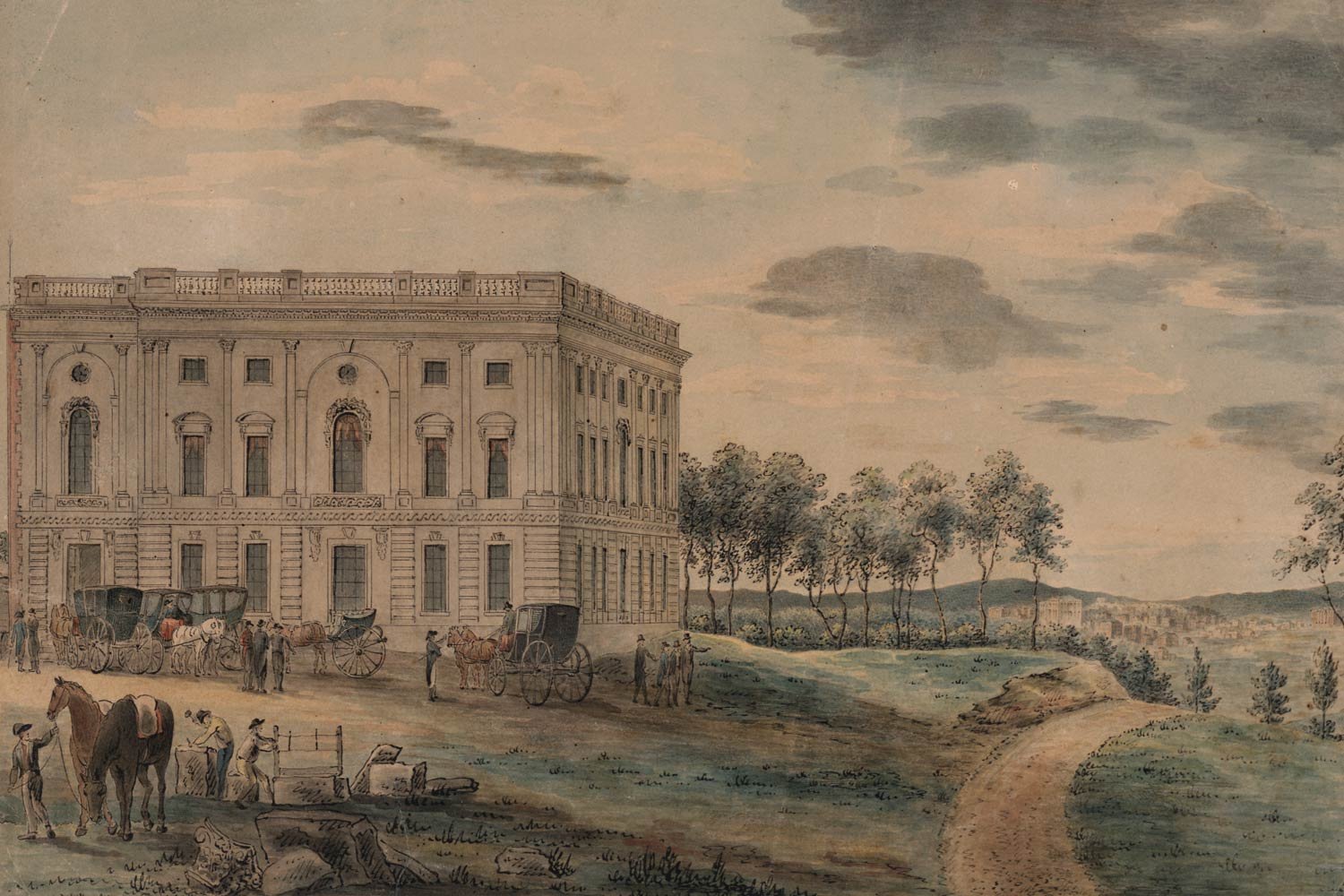

The presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.

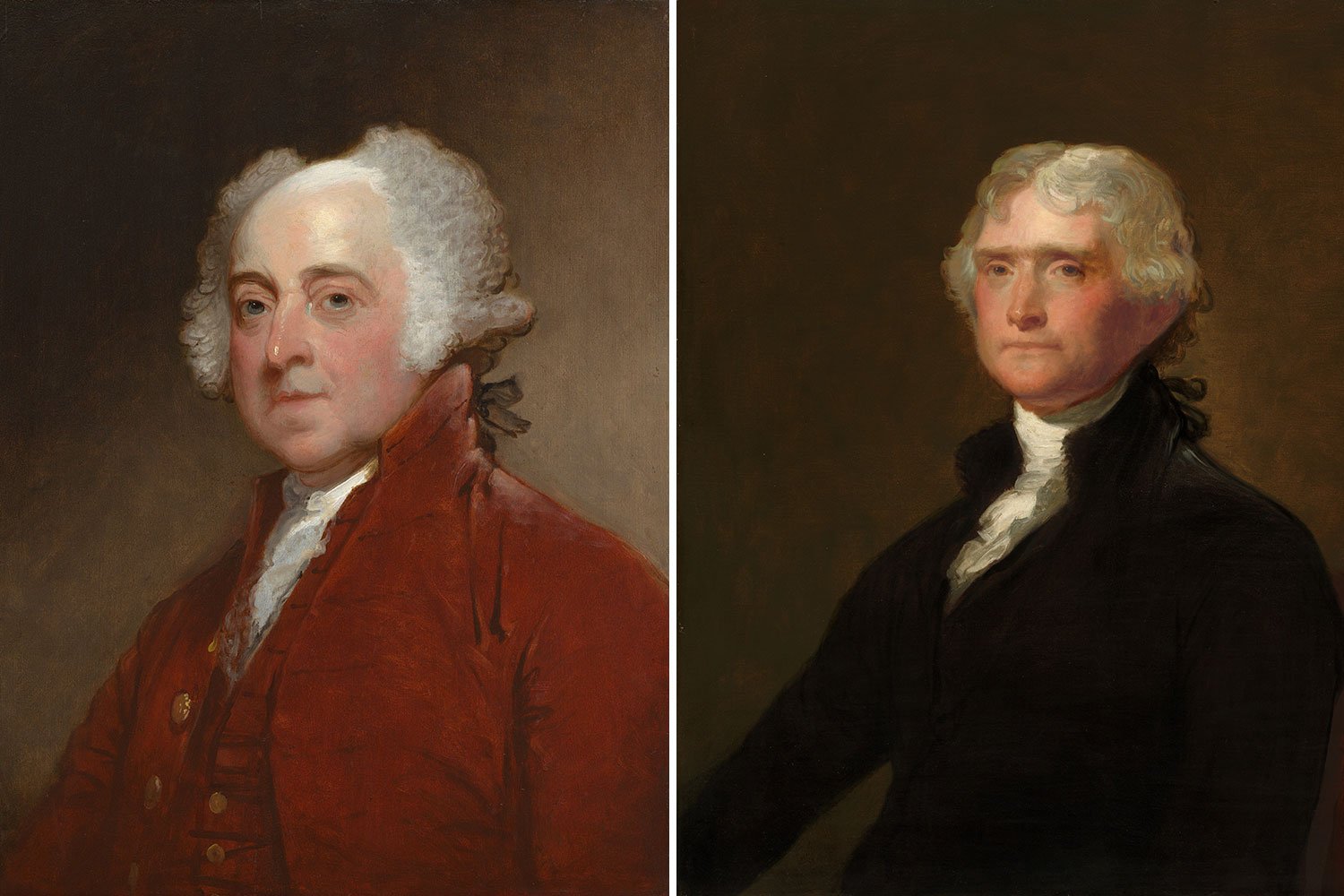

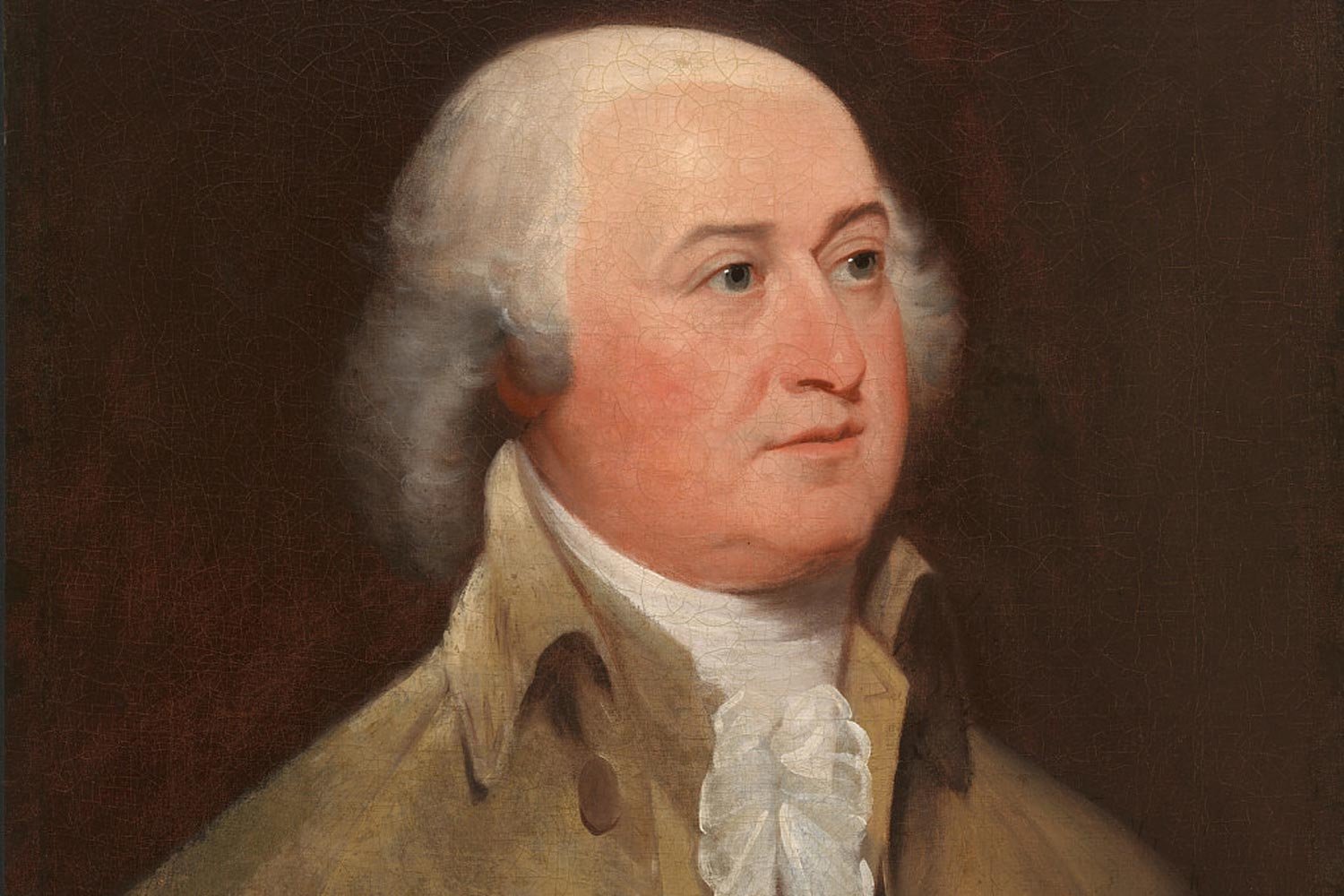

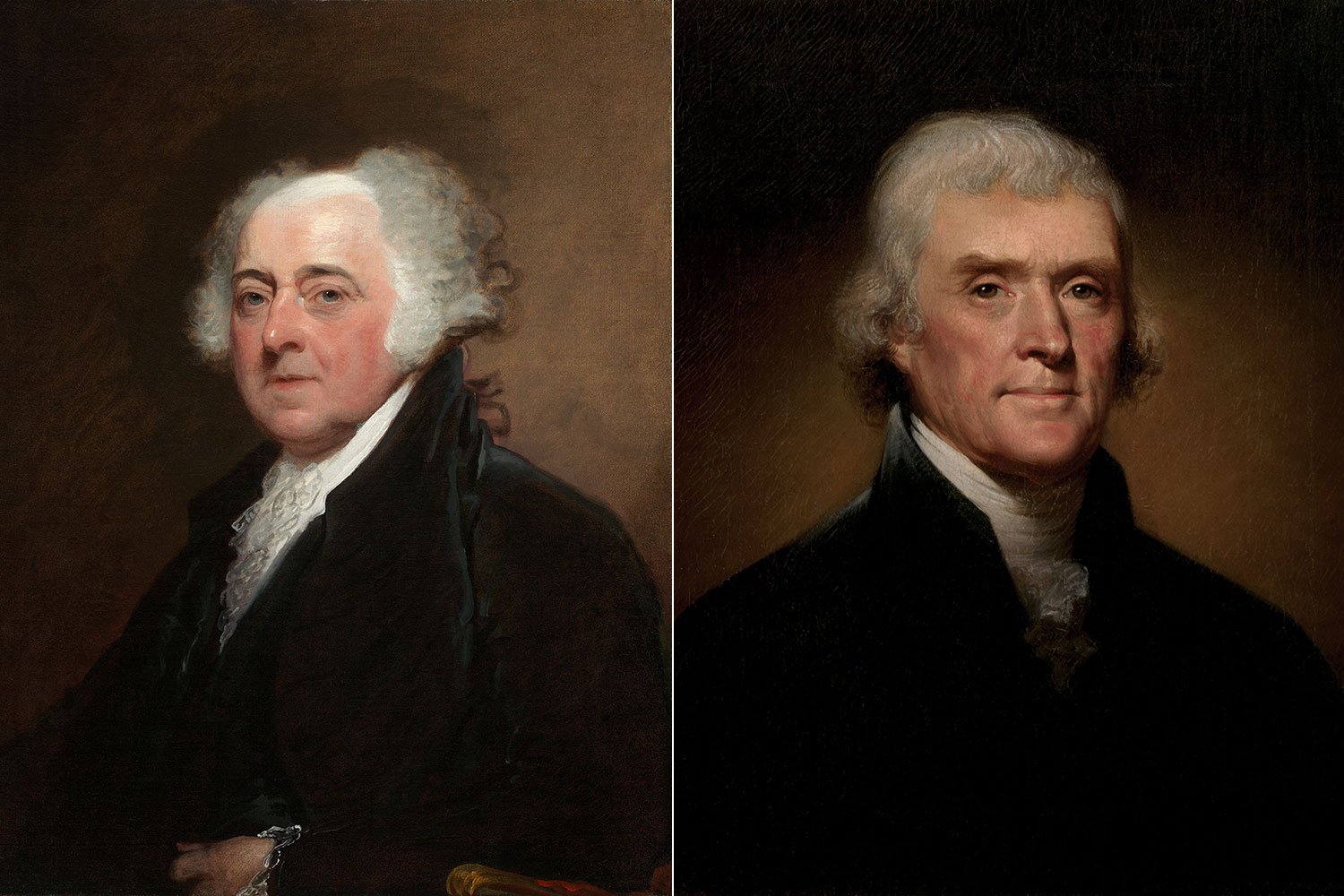

The opposing candidates were President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson; a rematch from the election four years earlier when Adams had edged out Jefferson for the right to succeed Washington as Commander-in-Chief. This oddity of having the President and the Vice President come from different parties was due to the manner in which a president was chosen when the Constitution was first created.

At the time of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, there were no political parties but rather individual men all pulling in essentially the same direction, and the delegates thought it best to have the two most capable or most popular individuals running the country. Additionally, they felt the election of the President was too important to be left to the people, viewed by many delegates as the unwashed and uninformed masses, what Alexander Hamilton referred to as “the Beast.”

Therefore, the delegates created Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution which laid out the methodology by which the country would elect its presidents. Clause 2 of the provision declared that the state legislatures would appoint “electors” with the number of electors from each state equal to the total number of federal representatives and senators. This system has come to be known as the Electoral College, although that term is not found in the Constitution.

Clause 4 stated that each elector would in turn cast votes for two candidates for president, with the top vote getter being declared president and the candidate with the second most becoming the vice president. With the advent of political parties, the flaws in this system became apparent.

By the time Washington retired and the first contested presidential election was held in 1796, two parties had been formed, the Federalists led by Alexander Hamilton and the Democratic-Republicans under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson. Not surprisingly, the country was divided and when electors cast their votes for president, Adams and Jefferson, now political opponents, received the most and second most votes. This issue would be resolved with the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, but it would prove to be very much a problem in the election of 1800.

The two men had once been fast friends when they shared the common goal of American independence and a common enemy in Great Britain. Sadly, when the goal had been achieved and the enemy vanquished, the two Patriots drifted apart as Jefferson came to resent the direction Adams and the Federalists were taking the country. While serving as President George Washington’s Secretary of State and later as Adams’ Vice President, Jefferson had worked behind the scenes to establish newspapers that criticized the two administrations and, perhaps more disappointing, had kept up a secret correspondence with French officials that undermined Federalist positions.

“The Election of 1800.” Americana Corner.

During President Adams’s tenure in office, Adams had kept the country out of war with Great Britain and France, but his Alien and Sedition Acts had been very unpopular. Perhaps even more detrimental to his chances of reelection was his acrimonious and very public disagreements with Alexander Hamilton, the true party boss of the Federalists. With Jefferson attacking the President from without and Hamilton from within, Adams seemingly had little chance to win.

Although neither party put forth an official ticket with a president and vice president, both informed their electors how to vote. Importantly, to avoid a tie, both parties asked one or two of their electors to not vote for the vice presidential candidate so their presidential candidate would win by at least one vote. The Federalists put forth President Adams as their top choice and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney from South Carolina as their “other” choice. Pinckney, who had practiced law before the war, had risen to the rank of brigadier general in the American Revolution, signed the Constitution, and, most recently, been minister to France. Being from the Deep South, Pinckney also helped regionally balance the ticket as most southerners were skeptical of New Englanders like Adams.

The Democratic-Republicans naturally nominated Jefferson, the party’s founder and icon, as their first choice, and selected Aaron Burr, a talented lawyer from New York and former Continental Army officer, as their second choice. As with Pinckney, Burr was chosen for his ability to regionally balance the ticket, specifically to bring New York and its twelve electors into the Democratic-Republican column. But, as time would tell, Burr was a wild card and primarily motivated by self-interest. Over the next decade, Burr would prove himself as ambitious as the devil and one of the all-time scoundrels in the country’s history.

In keeping with the times, neither Adams nor Jefferson actively campaigned as soliciting votes was considered beneath the dignity of the presidency. Most thought that men should not seek the position but rather appear disinterested in it and serve only if chosen for this great honor. Consequently, James Madison conducted the public campaign for the Democratic-Republicans and his mentor, Thomas Jefferson; Madison did so energetically and enthusiastically.

On the other hand, Hamilton ran the Federalist campaign, but he despised Adams (the feeling was mutual) because the President refused to be Hamilton’s puppet. Hamilton worked behind the scenes to get Pinckney elected president as Hamilton viewed the South Carolinian as more pliable and more easily manipulated than Adams. In the end, Hamilton’s scheming helped elect Jefferson and drive the Federalists from power.

Congress decreed that Election Day would be December 3 which meant that all electors needed to be chosen, and their votes cast by that date. Consequently, voting started in the sixteen states in October and concluded in December. To avoid a tie, both sides asked one of their electors not to vote for their vice presidential candidate. The chosen Federalist elector did as he was instructed and voted for John Jay instead of Pinckney. But the chosen Democratic-Republican elector clearly did not get the message.

When the final tally of electoral votes was counted in Congress, Adams had 65 votes, Pinckney 64, and Jay 1. But both Jefferson and Burr had secured 73 electoral votes; the dreaded tie had happened and now the House of Representatives would decide who would be the next president.

Next week, we will discuss how the House of Representatives decided the election of 1800. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

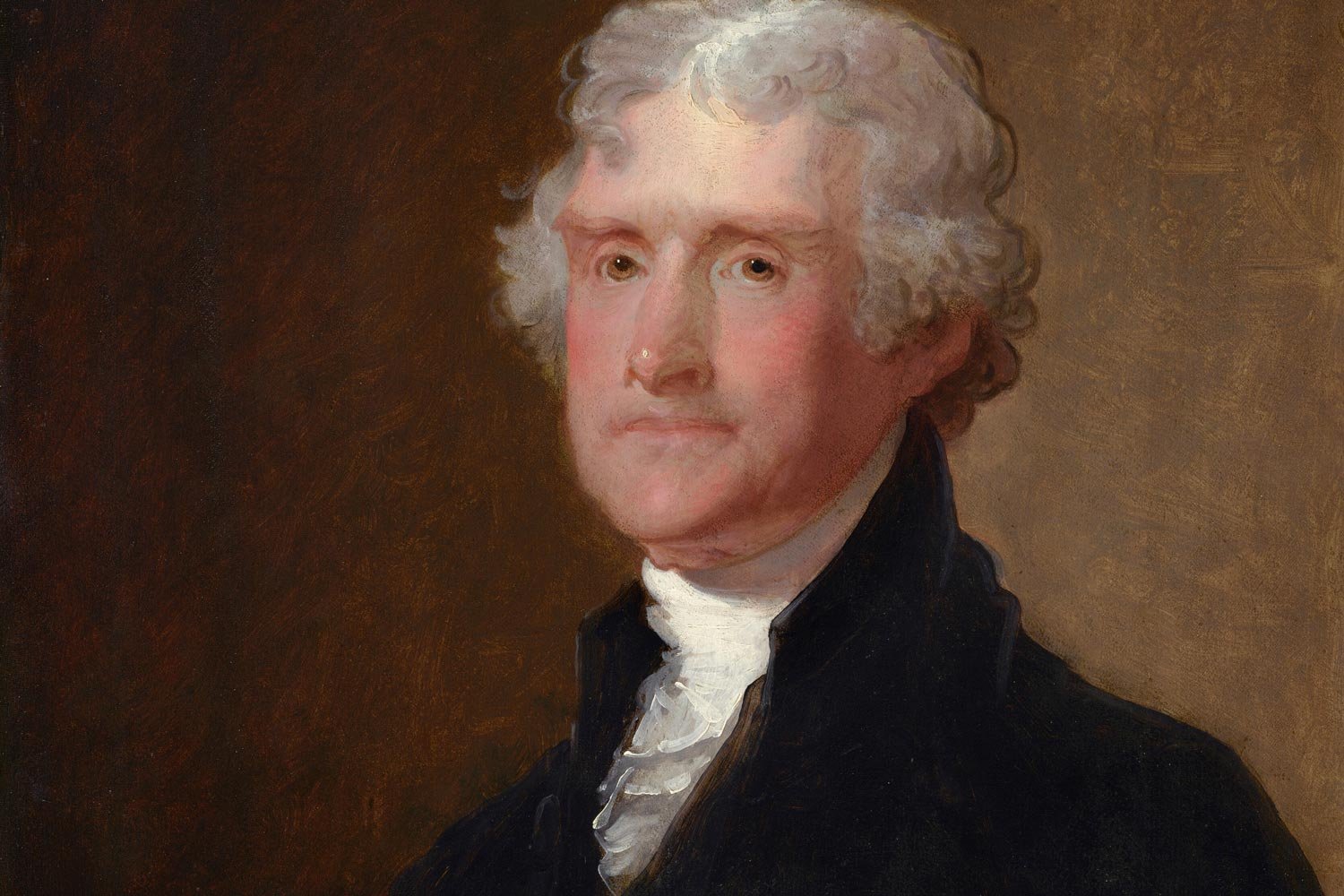

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.