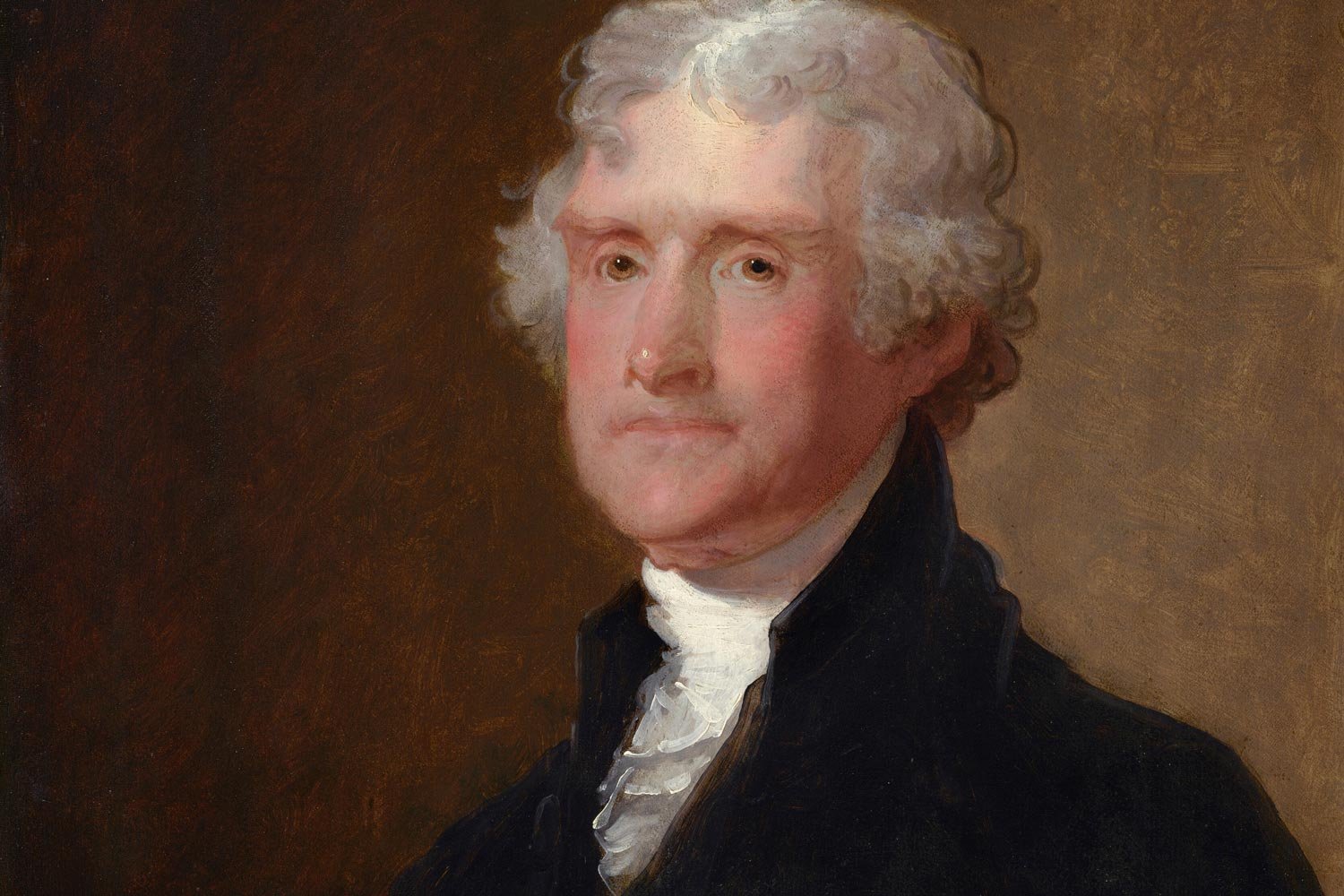

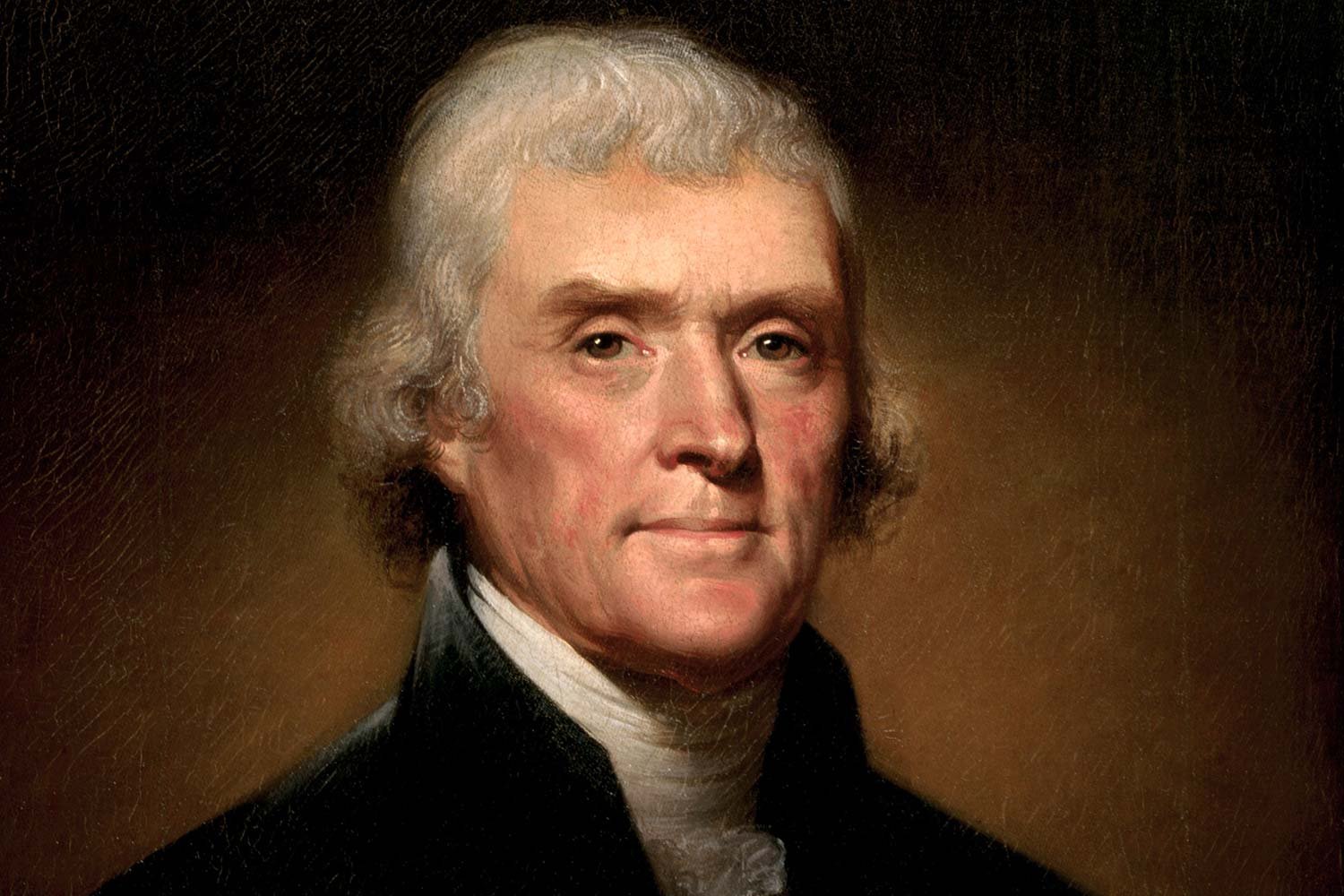

The Early Life of Thomas Jefferson

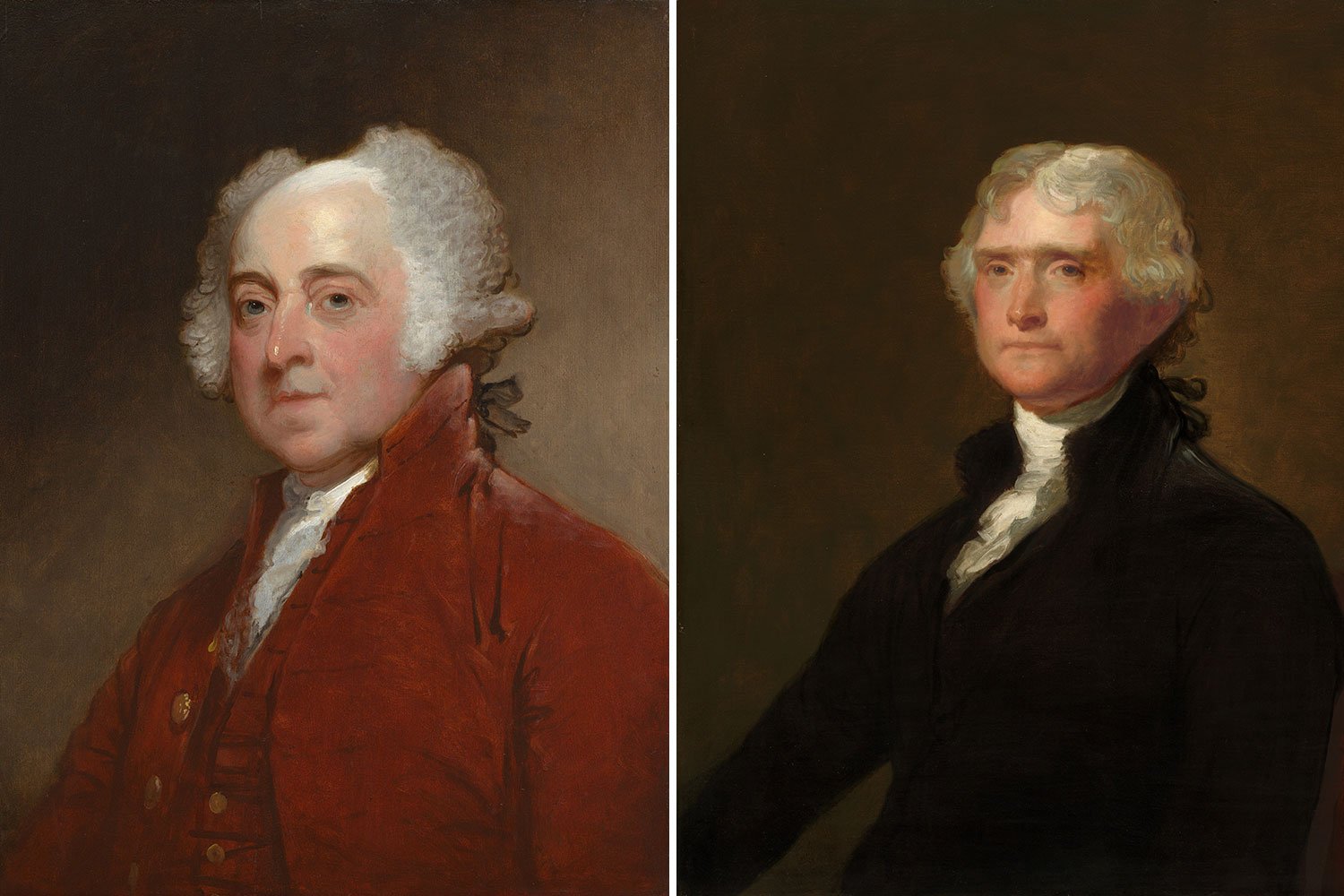

Thomas Jefferson is one of America’s most iconic Founding Fathers. Best known for his inspirational words in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was a brilliant man with diverse interests who spent the bulk of his life in service to his country and his later years in retirement at his beloved mountain home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. Jefferson influenced and shaped the early American republic to a degree only surpassed by George Washington and equaled by few others.

Thomas Jefferson, or Tom as he preferred to be called, was born on April 13, 1743, in a small one and a half story farmhouse on the frontier of western Virginia, in today’s Albemarle County. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a mountain of a man, known throughout the region for his prodigious strength. In addition to managing his two tobacco plantations encompassing some 7,000 acres, Peter was a noted surveyor and ranged far and wide over the western portions of the colony.

Tom’s great-grandfather, Thomas I, had emigrated from England in the 1680s and settled on a 167-acre farm in Henrico County. He was a skilled surveyor and hunter who augmented his farm earnings by collecting bounties for killing wolves. His eldest son, Thomas II, acquired the status of a gentleman as he increased the family land holdings, the measure of wealth in a planter society, and became a Captain in the militia and the sheriff of Henrico County.

But by the time he died, Thomas II had lost most of his wealth due to a devastating house fire, and Peter inherited very little, just some livestock and an undeveloped tract of land near the falls of the James River. Starting from scratch on a hard scrabble farm in the wilderness of Virginia, Peter cleared the land and carved out his homestead and rose to a man of some prominence in the county. In 1739, he courted and married Mary Randolph, the daughter of the Adjutant General of the county. This was a great marriage for Peter as it connected the Jeffersons to the Randolphs, one of the most important families in Virginia. Peter and Mary, who named their farm Shadwell after the parish in England where Mary had been born, had eight children together, with Tom being the third in line but the first son.

Because Peter was not the eldest son, his father had spent little money on Peter’s education, and he always felt a bit unpolished compared to his in-laws. As a result, Peter made the education of his children paramount in their upbringing and Tom developed a love for learning and books at an early age. When Tom turned nine, his father sent him away to school where Tom studied for five years under Rev. William Douglas. By the time Tom turned fourteen, he could read Greek, Latin, and French literature in the original.

Peter was away from home most of this time on surveying expeditions mapping the western reaches of Virginia and the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. His most famous map was the “Fry-Jefferson” map which charted the Allegheny Mountains for the first time and traced the Great Wagon Road, the main thoroughfare bringing settlers from Pennsylvania to the highlands of the Carolinas.

James Barton Longacre. “George Wythe.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

This work brought Peter significant wealth and contact with the leading authorities in the colony. He was promoted to Colonel and given command of the Albemarle County militia and was also elected as the county’s representative in the House of Burgesses. When Peter returned home from his trips, he would regale the children with stories of his adventures in the wilderness. As the oldest son, Tom spent considerable time with his father during these sojourns learning to shoot, hunt, fish, and survive in the wild; Tom adored his father.

Sadly, in the summer of 1757, when Tom was fourteen, his father got sick and soon passed away, perhaps “bled” to death by the local physician, who administered to him fifteen times in six weeks. Peter left behind a widow and eight children and a sizeable, debt-free estate. To Tom, who was devasted by the loss, he left roughly 3,500 acres, including the land on which Monticello would one day be built, and twenty five slaves to be held in trust until Tom turned twenty one.

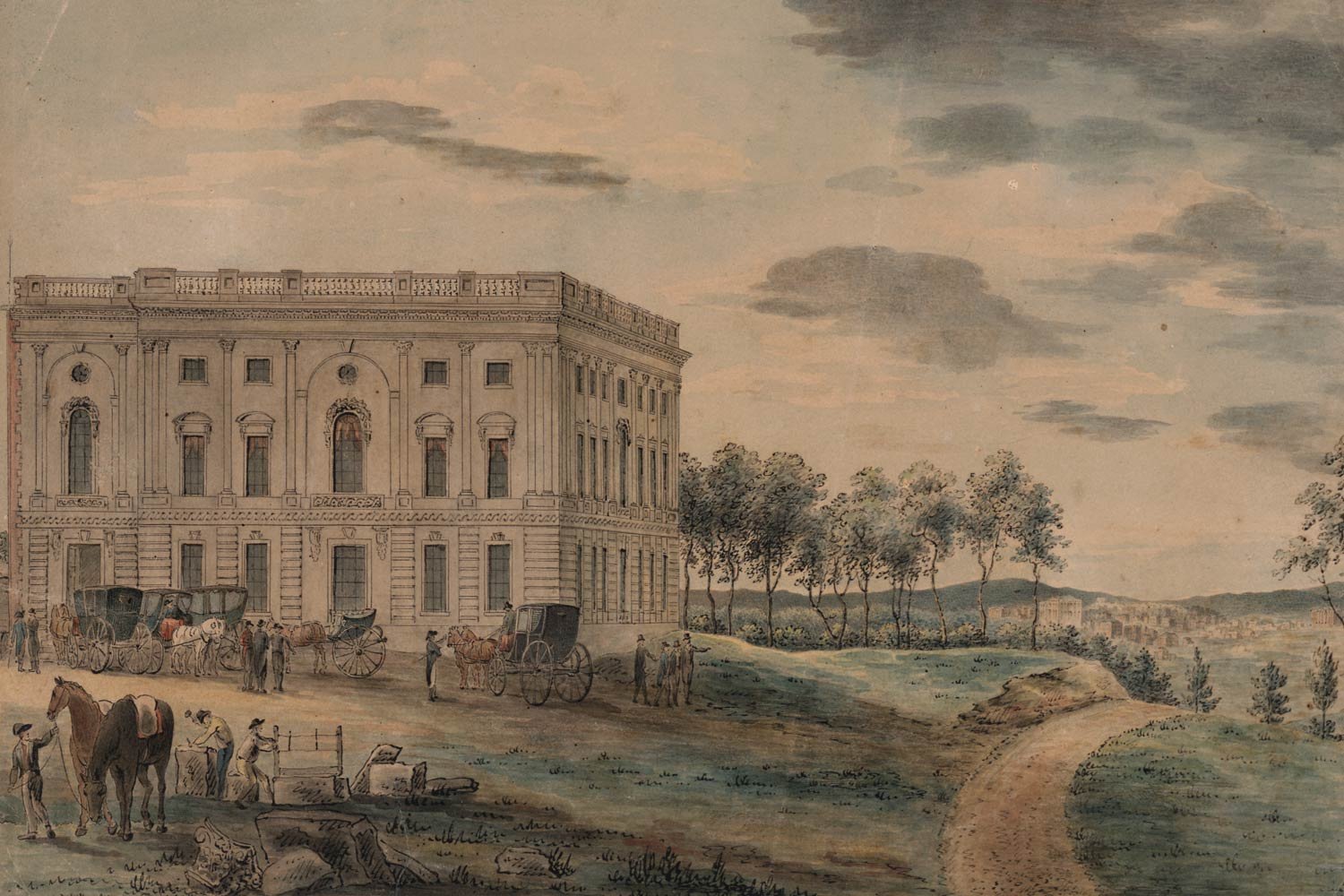

One of his father’s dying wishes was for Tom to complete his education, and the following year, Jefferson went away to study with the Rev. James Maury at his classical academy. Jefferson was there for two beneficial years and later stated he owed Maury a “deep and lasting” debt for the scholarship he taught Tom, as well as life lessons. With this classical education well absorbed, in March 1760, Jefferson left Shadwell for Williamsburg and the College of William and Mary.

Unlike most of his fellow students who were into horse racing, drinking, and gambling, Jefferson was very studious and spent as much as sixteen hours a day over his books. That is not to say Jefferson completely shunned the society of his schoolmates, but he was certainly more settled and more responsible than his peers. Although many of Jefferson’s classmates planned to simply live the life of a “gentleman planter” by living off the monies generated from their plantations, Jefferson knew this way of life was not enough for him.

Within a year, Jefferson decided he wanted to enter the legal profession, and, in April 1762, he left William and Mary to study law under George Wythe, the most renowned legal scholar in the colonies. Despite being self-taught in legal affairs, Wythe had a brilliant mind and a pleasant personality. Theirs would be a close relationship with Jefferson describing Wythe as “my faithful and beloved mentor in youth and my most affectionate friend through life.” Interestingly, Wythe, who also taught such American luminaries as John Marshall, James Monroe, and Henry Clay, considered Jefferson his favorite student and left his extensive law library to Jefferson in his will.

Jefferson concluded his time with Wythe in the fall of 1765 after passing his bar examinations and moved onto his brief but successful time as one of the top attorneys in Virginia.

Next week, we will discuss Thomas Jefferson’s law career. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

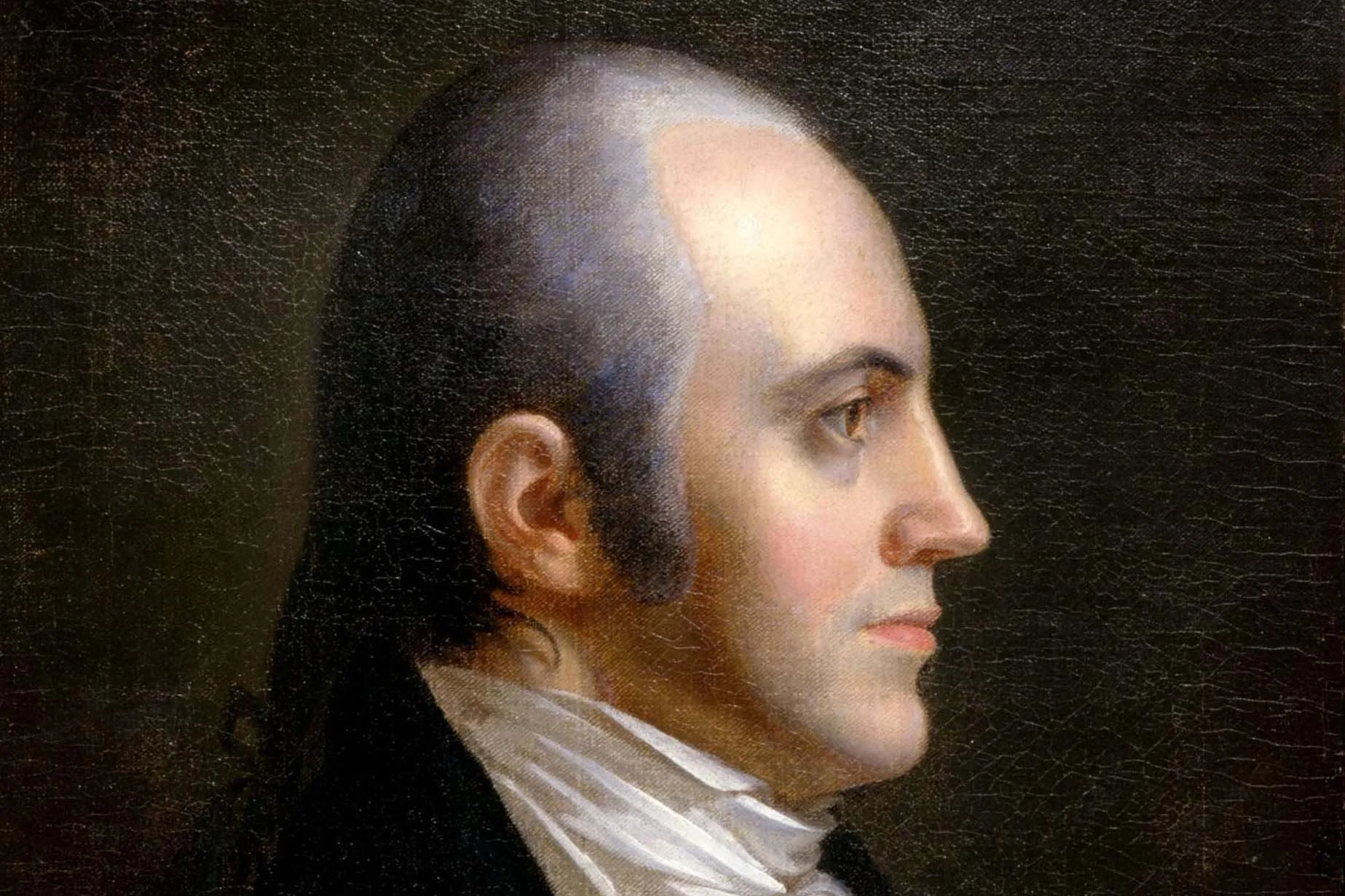

Aaron Burr's grand scheme to create his own country, possibly in Mexico or from United States territory, began to collapse late in 1806, practically before it ever got started. This empire in the sky built largely in Burr’s fertile mind was swiftly coming to an end.