The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

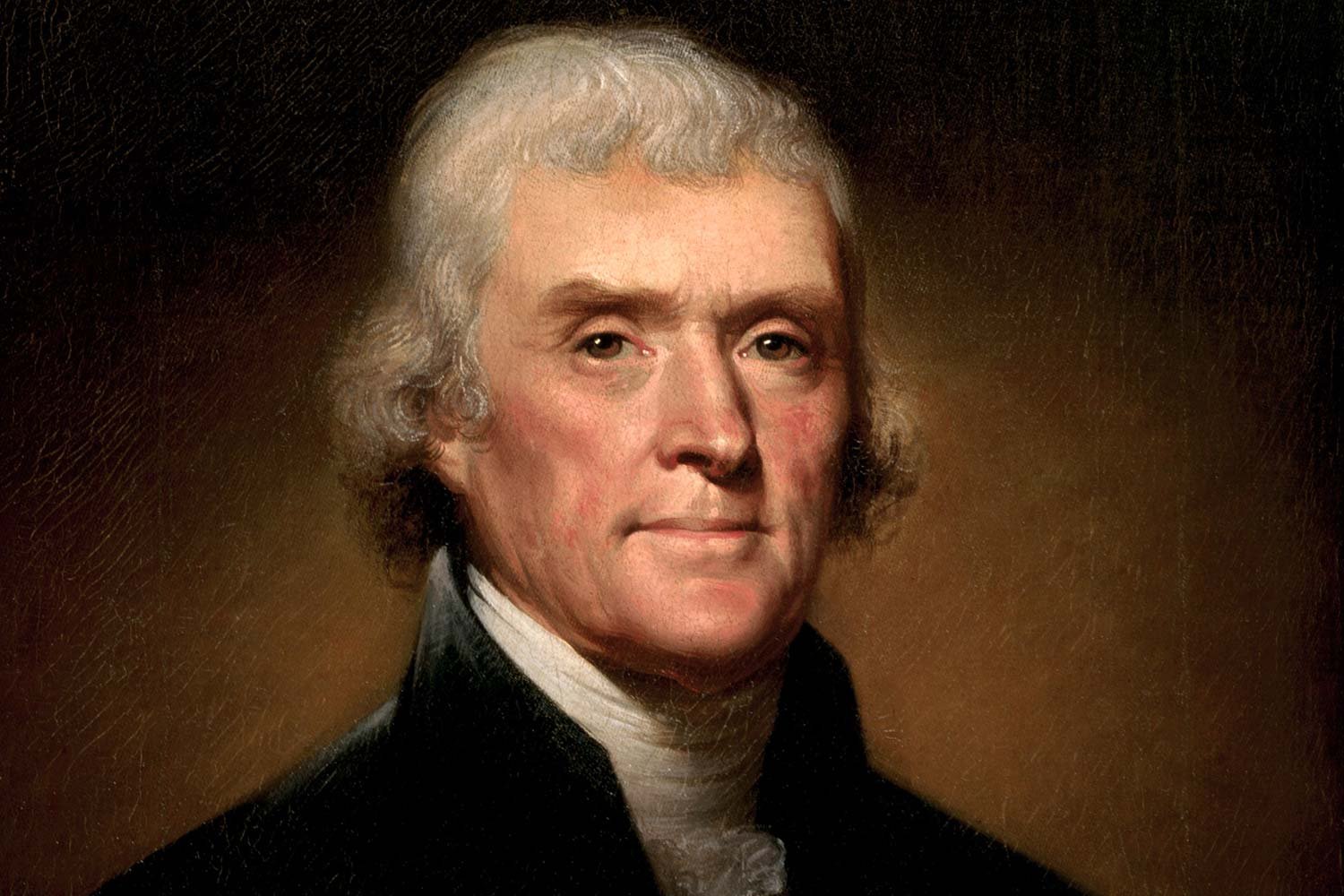

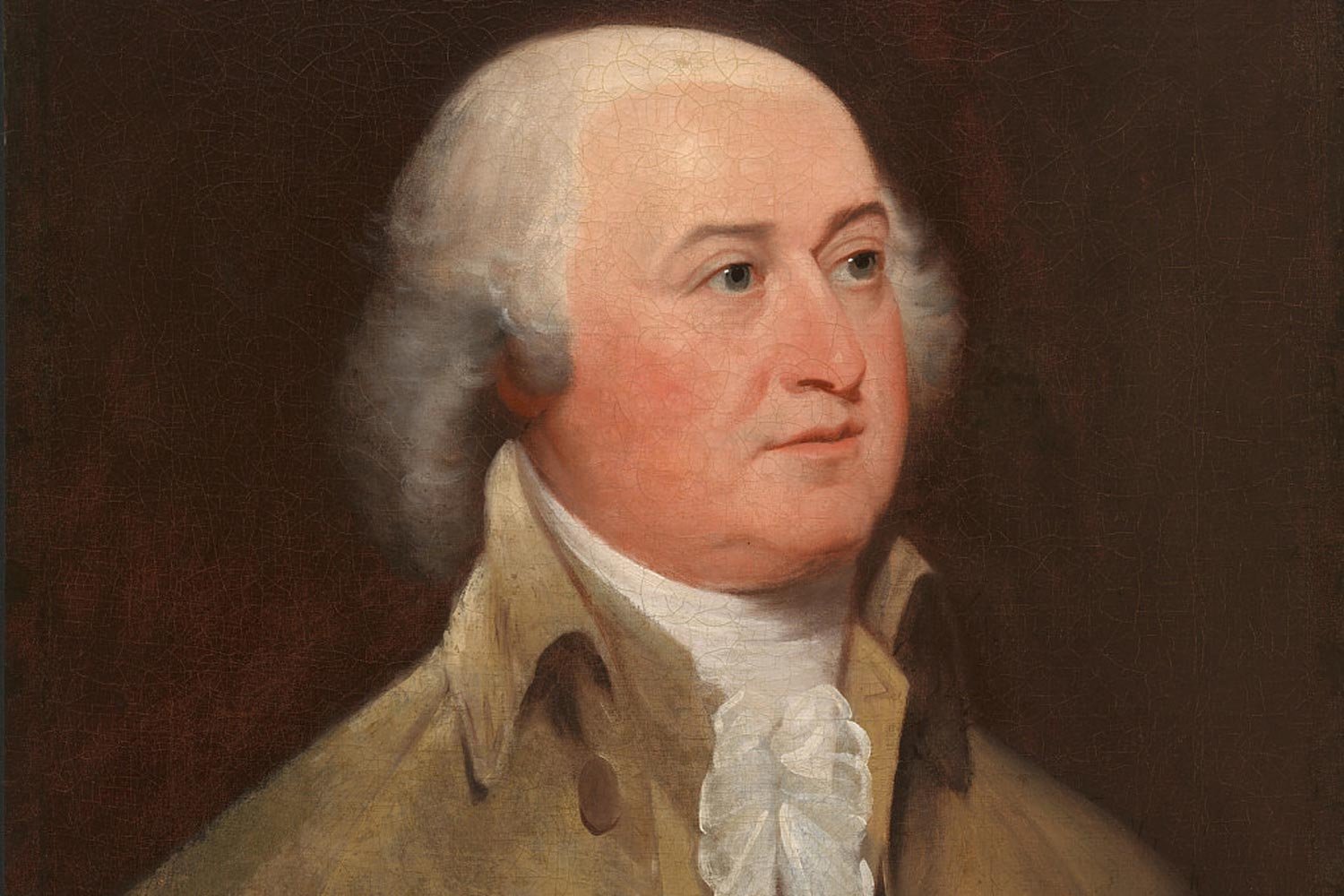

In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts passed by the Federalist controlled Congress and signed by President John Adams in July 1798, Democratic-Republicans howled long and loud about the legislation that they viewed as an assault on both their party and the Constitution. They turned to their leader, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, to counter these Acts and, if possible, use them to their political advantage.

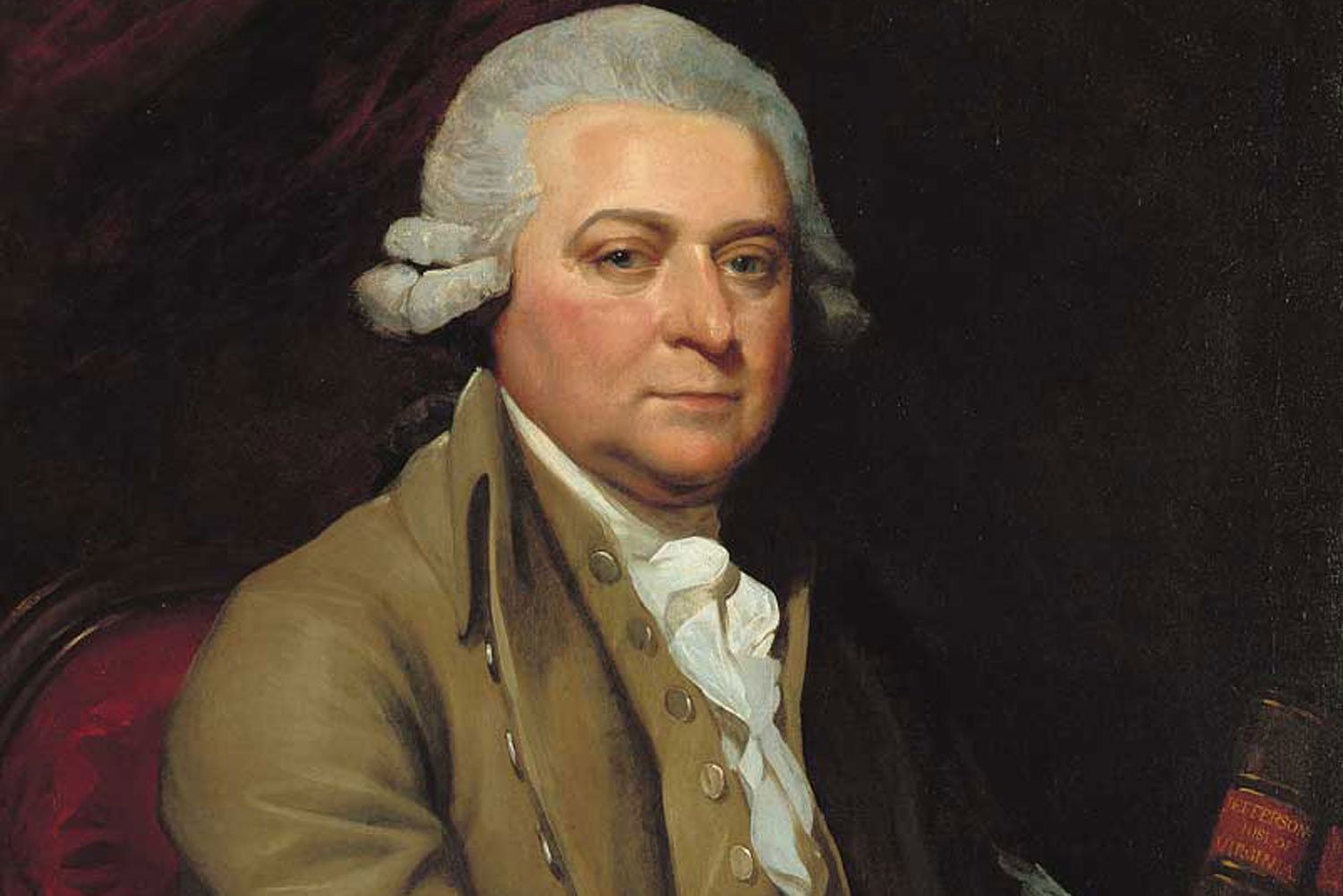

Jefferson was assisted in his efforts by James Madison, his fellow Virginian and brilliant political protégé. At the time of the laws’ passage both men were underemployed and residing at their homes, Monticello and Montpelier. Because the homes were only thirty miles apart, the two men were in constant contact.

Although Jefferson was the Vice President, he had little interest in helping President Adams and consequently spent a considerable amount of his time away from the capital planning his run for the Presidency in 1800. Madison had retired from the House of Representatives in 1797 and had kept very busy laying the foundation for Jefferson’s campaign.

Leading Democratic-Republicans viewed the Alien and Sedition Acts as a violation of the Constitution’s First Amendment, with Democratic-Republican Senator Henry Tazewell of Virginia saying the laws “indulge that appetite for tyranny” that would lead to monarchy. They were also greatly concerned that the Acts were a direct assault on state’s rights. But they were arguably even more worried about the laws’ adverse effects on their chances in the 1800 election.

Their newspapers such as the Aurora spewed forth bitter accusations, many of them completely false, against the Adams administration on a regular basis. The attack dog style articles assailed any and all Federalists including George Washington and had almost won the Presidency for Jefferson in 1796. Without the ability to print their propaganda, the Democratic-Republicans knew they could not win in 1800.

John Breckinridge of Kentucky and Wilson Nicholas of Virginia visited Monticello and pressed Jefferson to draft a resolution calling for organized resistance to the laws that they could present to their respective state legislatures. It was further determined that the legislatures should offer different versions of the resolutions so it would not appear that they were created in concert with one another.

Consequently, James Madison was brought into the mix to draft the Virginia Resolution and Jefferson the one for Kentucky. Recognizing that if it was known Jefferson and Madison wrote the resolutions that they would be charged with a crime, it was decided to keep the authors anonymous. Jefferson did not require much convincing to draft the resolutions and happily complied, with Madison following Jefferson’s lead.

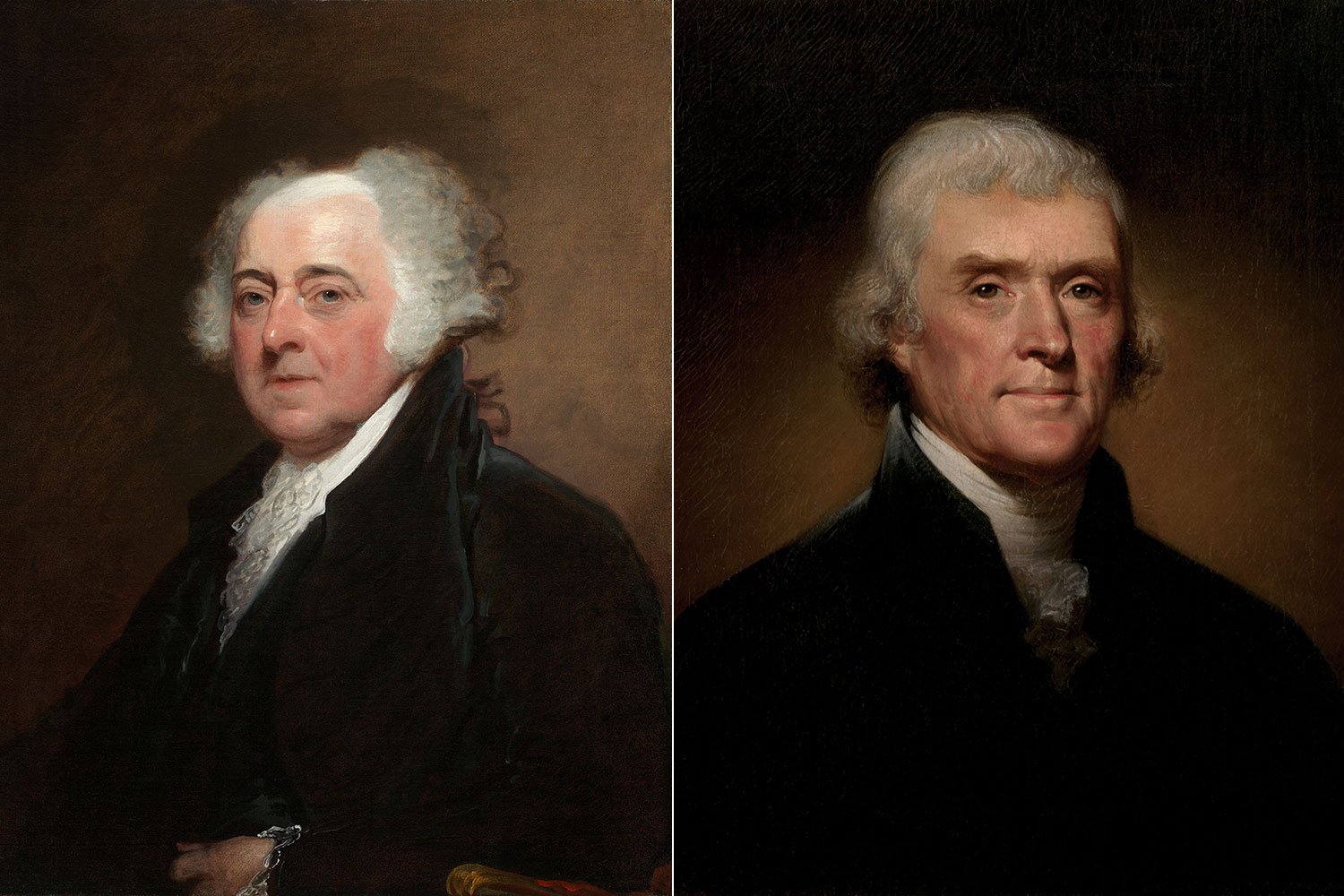

The two men created their drafts separately and they had distinct and important differences. In general, Jefferson’s version was much more radical, even dangerous to the preservation of the Union. Madison, arguably the brighter and steadier of the two Founding Fathers, drafted a more balanced argument against the Alien and Sedition Acts and a reasonable method of pushing back against them.

John Vanderlyn. "James Madison." The White House Historical Association.

Jefferson’s original draft of the Kentucky Resolution invoked the theory that the federal government was a compact of states, much like they had been under the Articles of Confederation, and that the states did not need to comply with federal laws they found to be unconstitutional. Furthermore, the test of the constitutionality of any law was to be found in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and could be judged by each individual state.

In Jefferson’s opinion, if the federal government passed a law that assumed an authority that was not expressly granted to it by the Constitution, then that law was unconstitutional, and the states were not bound to comply with it. In fact, Jefferson wrote the states “have the right and are in duty bound to interpose” against the implementation of the law. His initial draft went so far as to proclaim that the individual states had the right to nullify a federal law that the state judged to be unconstitutional.

This “nullification” doctrine was viewed by many Democratic-Republicans as dangerous to the preservation of the Union and thought Jefferson had gone too far. As a result, the Kentucky legislature struck that provision from the final bill, and simply asked that other states support their attempt to repeal the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Likewise, Madison’s Virginia Resolutions assumed a more moderate tone, much to Jefferson’s dismay, and asked for the various states to convene to discuss the matter. Madison did not agree with Jefferson that the states had the right to declare a federal law “null and void.” It must be remembered that Madison was arguably the foremost constitutional scholar in the country, perhaps only equaled by John Adams. Furthermore, Madison was the chief architect of the new Constitution which established the concept of the supremacy of federal law. Conversely, Jefferson had been away in France, serving as Minister, during the Constitutional Convention and had not participated in those vigorous debates.

Ultimately, both the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, as passed by their respective state legislatures, were rejected by every other state with Federalists accusing the Democratic-Republicans of favoring disunion. But these assertions of states’ rights by Jefferson would cast a long shadow and be revived from time to time for the next sixty years in the runup to our country’s Civil War.

Next week, we will discuss worsening relations with France. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.